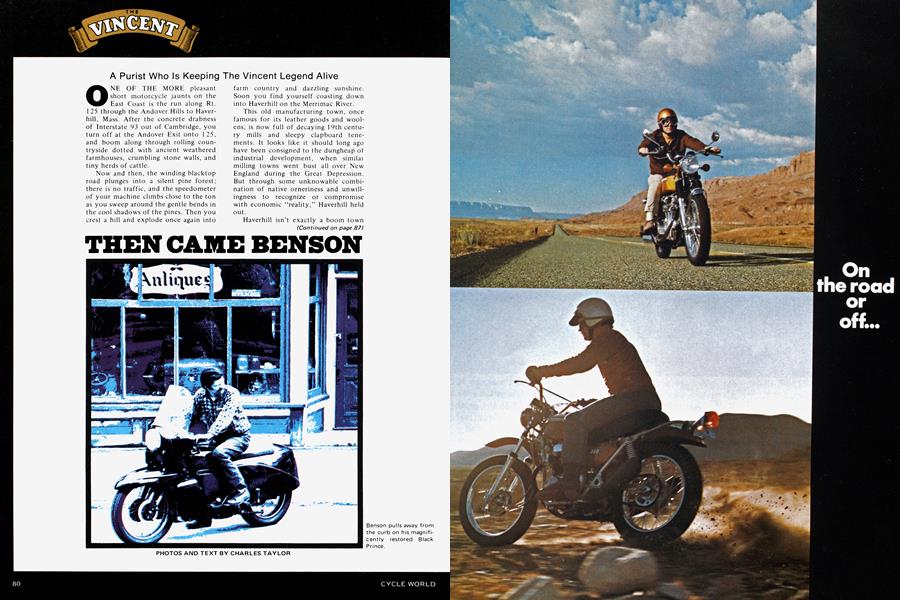

THEN CAME BENSON

A Purist Who Is Keeping The Vincent Legend Alive

ONE OF THE MORE pleasant short motorcycle jaunts on the East Coast is the run along Rt. 125 through the Andover Hills to Haverhill, Mass. After the concrete drabness of Interstate 93 out of Cambridge, you turn off at the Andover Exit onto 125, and boom along through rolling countryside dotted with ancient weathered farmhouses, crumbling stone walls, and tiny herds of cattle.

Now and then, the winding blacktop road plunges into a silent pine forest; there is no traffic, and the speedometer of your machine climbs close to the ton as you sweep around the gentle bends in the cool shadows of the pines. Then you crest a hill and explode once again into farm country and dazzling sunshine. Soon you find yourself coasting down into Haverhill on the Merrimac River.

This old manufacturing town, once famous for its leather goods and woolens, is now full of decaying 19th century mills and sleepy clapboard tenements. It looks like it should long ago have been consigned to the dungheap of industrial development, when similai milling towns went bust all over New England during the Great Depression. But through some unknowable combination of native orneriness and unwillingness to recognize or compromise with economic “reality,” Haverhill held out.

Haverhill isn’t exactly a boom town by contemporary standards, but it still manages to chuff along at a moderate pace. Its economic life is based on the variety and small successes of dozens of tiny enterprises. There are welding shops in profusion, places which under take nickel and cadmium plating, stove enamelers, and half a dozen antique shops specializing in Victoriana. And there is Coburn Benson's Merrimac Mo torcycle Sales, which deals in Triumphs, BSAs, and caters to the Northeast's die-hard Vincent freaks.

(Continued on page 87)

Continued from page 80

BENSON'S VINCENT WONDERLAND

From the outside, Benson's shop at 1 25 River Street is just another unpre possessing piece of false-fronted Victori an clapboarded real estate. Step inside, and you're in a kind of "you-don't-see many-more-of-these-anymore" motor cycling never-never land: Vincents, Vin cents, Vincents, a cabinet full of Manx parts, a Norton International, a 1938 Brough Superior SS 100 in for a top-end overhaul, a 1911 Indian Racer. . . and even a contemporary Triumph or two.

Standard Tricor signs and displays take up a small a~mount of space in the showroom window; pride of place goes to an immaculate remanufactured Series “D” Vincent Black Prince over which hangs an immense six-feet-long Vincent banner in black and gold. A Merrimac M/C Sales News Bulletin, detailing the latest racing exploits of Benson’s 1950 Grey Flash, is prominently displayed on the wall next to the side entrance to the shop.

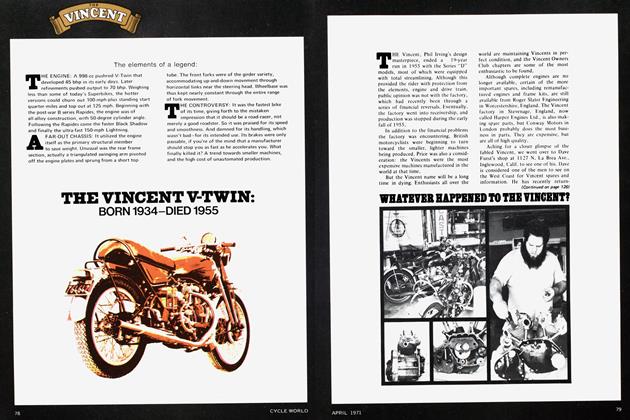

On a given day, Benson is likely to have several used Vincents for sale, as well as a Harper’s Engines remanufactured machine or two for the customer with an ample pocketbook. Harper’s Engines Ltd., a large English manufacturing concern, took over the production of Vincent spares several years ago, and, up until June 1969, were offering works-overhauled machines for sale on a limited basis. The spares supply continues, manufactured in the old Vincent plant in Stevenage, Hertfordshire. Some of Philip Vincent’s original employees still work there. Spokesmen for Harper’s Engines/say that as long as the demand for spares holds up they will do their best to meet it; but alas, the works overhauled machines are no longer available.

The remanufactured machines are beautifully finished. Welds are almost invisible, and the deep-gloss black enameled tank and cycle parts are set off with perfectly applied gold-leaf striping. The wheel rims have black enamel centers and chromed sides separated by delicate red pinstriping. As on the original Vincents, there is liberal use of stainless steel and polished alloy components.

They are fitted with higher compression pistons to take advantage of modern fuels, and the old side-float pattern carburetors have been replaced by Amal concentrics; otherwise, the machines are completely original. They are virtually brand-new from the crankcase up, and come with the traditional 6000-mile, four-month warranty, and a detailed list of the parts replaced during the overhaul.

Asking price is $2000, which, while a bit steep, is not all that bad in this day of $1800-$ 1900 “superbikes,” and not bad at all when you think of the prices asked for many used Vincents in the classified sections of CYCLE WORLD. Best of all, the customer knows that a remanufactured Vincent will be set up right. Many Vincent owners have almost as much money tied up in their worn machines, and they still can’t get them to perform the way they should.

THE REBUILDING PROJECT

At one time, Benson was thinking seriously of rebuilding and guaranteeing Vincents himself. He acquired some working space at Jay’s Motorcycles in Cambridge, Mass., and bought 10 running but shaggy Shadows and as many wrecks for spare parts, and shut himself up for the winter.

His plan was to assemble 10 machines from new and sound used parts, and sell them for $1000 apiece in the spring. Unfortunately, he was only able to assemble seven and sell five. He barely managed to break even, and decided that the whole scheme was not worth the effort, in view of the long hours involved and the difficulty of obtaining really large quantities of warranted new parts.

But he did end up with one of the largest collections of used Vincent spares and machines on the East Coast. He still has a barn in Concord, Mass., on the old family farm, well stocked with wrecks and good used parts, and a shed behind the shop in Haverhill which, at last examination, contained two Shadows, a Rapide and a ratty-looking Comet Single.

His Vincent work now consists mostly of repairs on customers’ machines, special racing modifications and speed tuning. He has more than enough to keep him busy. The last time I made the trip to Haverhill to pick up some parts and rap for a while, Benson was making the following modifications to a customer’s Shadow engine: Alpha big-end assembly, theoretically disaster-proof up to about 7500 rpm, which is really flapping for a 1000-cc V-Twin; cams of his own (classified) design; 10:1 pistons; porting and polishing the heads to take 1 1/4-in. IT earbs (easier to tune than the GPs, says Benson); anil judicious lightening and polishing of the valve gear.

(Continued on page 146)

Continued from page 88

These modifications, in conjunction with a straight-through exhaust, should give the customer something like 75 bhp to play around with on the street. The standard Black Lightning, with similar internals, used to deliver upwards of 70 bhp with slightly smaller carburetors and a 9:1 compression ratio, so Benson’s estimate of power output is probably on the conservative side.

One of the nice things about the Vincent engine, says Benson, is the extent to which it can be modified before it becomes truly “strung out’’ and unreliable. The engine’s robust internals, including the four main-bearing crankshaft, the 2-in. erankpin, and the massive 1-section, high-tensile steel rods riding in an impressively strong and rigid crankcase, make it virtually indestructible.

The old Black Lightning engine, while delivering an honest 70 bhp from 998cc, was in a relatively mild state of tune compared to, say, a Triumph Bonneville engine producing 5 2 bhp from 650cc. The prospective engine tuner can confidently expect to get into the 80-90 bhp range on gas before encountering serious reliability problems. So when Benson twirls his drooping moustache and gestures in the direction of the aforementioned customer’s machine, saying “. . . and it’ll be fully streetable and idle down like a Buick Eight,” he isn’t putting anybody on. Well, not much, anyway.

A GREY FLASH GUINEA PIG

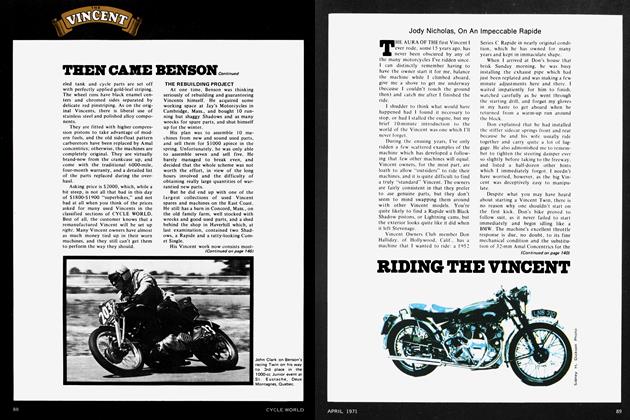

Benson his two assistants and close friends call him Ben does most of the research and development work that eventually finds its way into customers’ machines on his ancient Grey Flash road racer. This is a 500-ce production racer made in limited quantities by Vincent in the early Fifties.

The machine, as delivered from the works, used to produce about 35 bhp on an 8:1 piston at 6200 rpm. Benson’s modifications, including an Alpha bigend, 11:1 piston, 1 1 /4 Amal GP carburetor, home-brew cams, and extensive lightening and polishing of the valvegear and other highly stressed internal components, have resulted in an engine which puts out close to 50 bhp almost as much as a Norton Manx.

The engine’s reliability and the machine’s relatively light (300 lb.) weight make it competitive with most of the classic British single-cylinder production racers still being campaigned all over the world. Since a Vincent Twin is, in effect, two Singles on a common crankcase, information gained from modifications to the Flash can be applied directly to the Twins. The advantages of the Flash as a vehicle for experimentation are obvious: it is simple, and if anything breaks, the damage will he less extensive and expensive than on a Twin.

ON HANDLING AND STOPPING

What about handling and stopping, the alleged twin failings of all Vincents? “Ever since that CYCLE WORLD road test on a Lightning a couple of years back,” says Benson, “I’ve been running into people who put down Vincent handling and braking, and the clutch too. And you know,” he continues, “half of them haven’t even seen a Vincent, much less ridden one.” Benson gets worked up over the phenomenon of “Honda generation” critics of the Vincent legend, and magazine criticism from “people who should know better.”

“Let’s take the matter of the clutch first: is it reasonable to assume that all Vincent clutches slip, just because the one in the CYCLE WORLD road test did? I mean do you think that Phil Irving designed it that way? If the Vincent clutch is assembled carefully with new oil seals and religious attention is given to cleanliness, and if you keep an eye on the oil level in the primary case, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t get trouble-free service from the unit.

“1 know people who’ve driven around with the original Vincent clutch for years without any problems at all. In fact, they claim they get better mileage and dependability from it than from an ordinary multiplate clutch.” (The Vincent unit is a serve-clutch operated centrifugally by engine revolutions.)

(One of these “people” who can attest to the reliability of the Vincent clutch is this writer, who, in the course of the last five years, has owned three Black Shadows and a Rapide, none of which has needed anything other than routine maintenance in the clutch department but. naturally, I’m biased.

“Handling?” says Ben, “...well, let’s be for real. Vincent handling was great compared with whatever else was around back in the Forties and early Fifties. Remember all those plunger BSAs, sprung-hub Triumphs, and rigidframe hogs? Compared to them, the Vincent handled like a road-racer; in fact, about the only thing you could get that handled better were the early Manxes and Velocette production racers.

“Vincent went out of production in 1955, at just the time when the rest of the industry was beginning to make real advances in suspension technology. If Vincent had stayed in production, they would have had to come up with a new frame and suspension to maintain their reputation for fine handling.

“By today’s standards, their handling would be judged only fair. They do get kind of snaky when banked over hard for a fast corner on a poorly surfaced road, but if you don’t push them, they’re okay. Most of the people who put down Vincent handling are incapable of driving the machine to its limits anyway.

“When it comes to straight-line highway cruising in the 90to 100-mph range, though, I’ll take a good Vincent over just about anything on the market today. Seems like the faster you go, the steadier those C.irdraulic forks become. There’s absolutely no wandering and hunting like you get with even the best telescopic forks at those speeds, and the suspension dampening is more than adequate for most surfaces.” (The Vincent “Girdraulic” fork, introduced in 1949, combines the twist-resistant characteristics of the old-fashioned girder fork, and the hydraulically dampened springing of the telescopic fork.)

“Now remember, I said a good Vincent,” continues Benson. “ They’ve been out of production for 15 years now, and not all owners have the know-how to do first-class maintenance work on their own machines, and, excepting certain parts of the country (like Haverhill), you can’t just go down to your friendly local Vincent dealer to get the work done.

“Most bike dealers don't want to take the responsibility of working on such an old and rare machine, or say they can’t get parts and so forth. In fact, if you don’t know about people like Harry Belleville in Marysville, Ohio, Gene Aucott in Philadelphia, the Vincent Owners ('lub, or me, you really can’t get parts. And things like shock absorbers, hydraulic dampers, springboxes, fork spindles and so on tend to wear out fairly quickly, while they re often the last things that a motorcycle owner is going to replace, especially il he thinks parts are hard to get.

“So the result of all this is that there are a powerful lot ot truly shaggy rat-Vincents with shot suspension systems running around in the woods. 1 he well maintained, properly equipped Vincent is somewhat of a rarity. Needless to say, all those privately maintained rats don’t help the Vincent reputation.

“Christ, the other day some New Hampshire farmer came in with a '51 Shadow which had an old tabacco tin for a clutch cover, bone-dry dampers, no brakes at all, and ‘Vincent Black Shadow’ scrawled on his tank in white house paint. The letters were 4 in. high and looked like they'd been put on with a broomstick. He said all he needed was a tune-up. Fastest farmer in Plaistow, N il., eyup.”

. . . AND BRAKING?

On the subject of Vincent braking, Benson has this to say: “The stories about Vincents not being able to stop are ridiculous. Again, it’s a (tuestion of lots of Vincents on the road having worn linings and out-of-round drums. If you look back at some of the early road tests of brand new machines, you'll find that the Twins (and we’re talking about a 460-lb. motorcycle), could stop in something like 22 ft. from 30 rnph. The Singles stopped even quicker than that. That’s damned good stopping even by today’s standards.

“ The old Vincent duo-brake system, which some of today’s road racers are just beginning to use, really worked; it was reasonably fade-resistant let’s face it, lining materials have improved in the last 15 years and it stayed dry, thanks to Vincent’s system of light-alloy water excluders on all four brakes.

“If anything, the Vincent had too much stopping power. The factory recognized this, when, in the last year of production, they left off one of the rear brakes altogether, relying solely on the front duo-brakes for serious stopping and leaving on the single rear brake as an auxiliary, more than anything else.

“Old Man Vincent was so confident of the stopping power and controllability of his machines that he often drove his prototypes up to 100, and then seized up the front wheel to demonstrate these qualities to sceptics. That’s one of the reasons lie's got a steel plate in his head and has lost most of his coordination.” (Author's note: Phillip Vincent was involved in a serious crash in 1947 while road testing a prototype Black Shadow. He suffered internal head injuries and a partial loss of coordination. and as a result was never able to ride a motorcycle again. )

“Of course there are things you can do to improve the handling and stopping of the standard Vincent. " Benson continues. “You can get rid ot the snakiness during hard cornering by replacing the standard rearsprings with heavy-duty sidecar units. I he dampers can be filled with 50-weight oil instead of the normal 20, if the damper seals are still good or, better yet, Koni makes a special damper to fit the Vincent. They cost about twenty-two bucks apiece, but if you want fine handling, that’s not too much of a price to pay.

(Continued on page 148)

Continued from page 147

“If you want good, consistently fade-resistant braking, replace the original linings with Ferodo ‘green stuff’. . . and be sure to synchronize the brakes on each wheel, especially the front. That’s a point a lot of Vincent owners overlook.”

Vincent front brakes are synchronized by adjusting the position of a torque arm which picks up the motion from the two brake cables and transfers it to a single cable connected to the brake lever. There are four points of adjustment, and synchronizing the brake can be difficult if it is allowed to get out of whack, and different wear patterns on linings and drums develop.

“That’s all very fine,” 1 told Benson, “but isn’t the necessity for all these modifications proof that the Vincent is basically an unperfected machine?” Benson smiled, and poured himself another cup of coffee from the old tin pot which was bubbling merrily on the electric plate that doubles as a cylinder liner removing aid.

“Yes and no,” he resumed. “In 1950, the heyday of Vincent’s prestige, a Vincent Twin was the most ‘perfected’ motorcycle you could buy. It represented the quintessence of pre-war handcrafting, and post-war materials and technology. Today, it’s ‘unperfected’ in the same way a Bugatti or a Bentley racing car is ‘unperfected.’ It’s unfair to judge an older machine out of th e context of the technology of its own time.

“But the interesting thing about the Vincent is that it can be updated so easily, and that so many people are willing to spend a lot of time and money to do just that. I always tell the doubters that the Vincent is the best ‘kit’ d o-it-yourself motorcycle around today; you get the best metals, the best workmanship ever, and you can assemble it anyway you want.

“Starting with the basic machine, you can make yourself a real ‘Superbike,’ and in this day of Honda-generation, disposable beer-can-metal motorcycles, that’s saying something. When you’ve finished ‘perfecting’ your Vincent, you’ve got something that sets you off from the rest of the crowd, that says ‘This guy really knows his machine.' Why I imagine that most of the people you see riding around on Honda Fours have exhausted the limits of their technical knowledge when they remember to turn on the gas before punching the electric starter button.”

PROSPECTS FOR AN EGLI FUTURE

What does Benson think of the FgliVincent, that latest in a long line of attempts to bring back the Vincent? “Well, Kgli’s basic concept is sound: put the old engine-transmission unit in a new, lightweight frame, use Cerianis up front and disc-brakes. All the road tests I’ve read on the Kgli-Vincent seem to indicate that the new combination handles quite well for a big machine.

“But the performance figures of the Fglis don’t jive with the claimed bhp; in fact, if you look at the old road tests from 20 years back, you’ll see that the ‘New’ Vincents are slower than the old.

The Fgli-Vincents turn in mid-14-sec. quarter-mile times. That’s about as quick as a 1 948 Black Shadow on 7.3:1 pistons and post-war ‘pool’ gasoline, using a whopping high 7.2 bottom gear to boot! A good Series C' Shadow (1949-53), with 9:1 pistons and the stump-puller bottom gear which became standard on all (' Twins, should run in the middle 13s with a trap speed of slightly over 100 mph, and this on 55-60 bhp, as opposed to the 65-70 bhp claimed for the Fgli.

“I think what is happening is that some of the old hand-assembled qualities of the early Shadows have been lost. Fach Shadow that came off the assembly line was, in effect, blueprinted.

All parts were carefully selected within the limits of manufacturing tolerances. For instance, Shadow pistons and barrels were graded into four sizes for perfect fit. All the pieces that didn’t come up to Shadow standards were put back on the shelf, or were assembled into Rapides, the basic work-a-day Vincent Twin. This is a mighty expensive and painstaking way to make a motorcycle, but it worked. And when Vincent claimed 55 bhp and a top end of around 130 mph for his machines, he wasn’t lying.

“Fgli appears to be taking reworked old Rapide engines, stuffing high compression pistons, Lightning cams and fat concentric carbs into them, and then making outrageous bhp claims for them which just aren’t borne out by test results. Still, I wouldn’t mind putting one of my Shadow engines in an Fgli frame. I understand Gene Aucott (Philadelphia) has several frames for sale, as well as complete Fgli-Vincents.”

Benson would appear to be not far from the truth on the matter of oldtime Vincent performance. Recently Super-Cycle, an Fast ('oast publication dedicated to “The Big Bike Fnthusiast,” road tested a 1952 Black Shadow loaned them by Ghost Motorcycles of Port Washington, Long Island. The machine was fitted with Black Lightning cams and high compression pistons; otherwise, it was completely stock. Its quarter-mile time was 13:01 at 106 mph. Top speed was 144 mph, with full road equipment, lights, muffler and no fairing, certified by NUR A clocks. There is no road machine being manufactured today which can turn in a better all-around performance. A stock Black Lightning, needless to say, should be even faster.

Benson is not overly optimistic about the future of the Kgli-Vinccnt: “If, in 1970, they can’t put together a motorcycle that’ll outhandle, outstop and outperform the original Vincent, if they can’t build a machine which sells for slightly over $2000, finished with as much attention to detail as the original, then they’re doomed to failure.

“Cost is not the object in America, and it never was with the Vincent: the old Shadows used to cost upwards of $1400 in the Fiftiesthe price of a good car. But when someone lays out that much money for a motorcycle, he wants to know that he is getting the best. Twenty years ago, the Vincent was the best. Today, the Fgli-Vincent doesn’t seem to be as good, all told, as the original. You might as well go buy a

Honda Four.”

Benson is 35 now, makes a good living as a Triumph and BSA dealer, and still manages to find time to work on customers’ Vincents and tend to his own private stable of exotic machines, lie’s got a representative of every postwar Vincent made, and lie’s looking around lor an early series A pre-war Rapide onto which he can graft the upper works of two pre-war IT Replica 500s. “Imagine cruising down the turnpike at 115 in third on that oo/.ing plumber’s nightmare, and then shifting into fourth as you pass some poor mind-shattered bloke on his showroomnew Triumph Triple.”

He’s continually toying with new schemes to enhance the Vincent legend. Right now, he’s talking about building a Vincent to go after the 24-hour production record, and you never know, he just might do it. “If I could just get away from my Triumph and BSA customers long enough to put some serious work into the Vincent project, shut off the phone, bolt the door, hang out a sign saying “(jone to Stevenage on Business, be back next year,” and retire to the farm in C’oneord but that’s like talking about installing gaslights at the Pentagon.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue