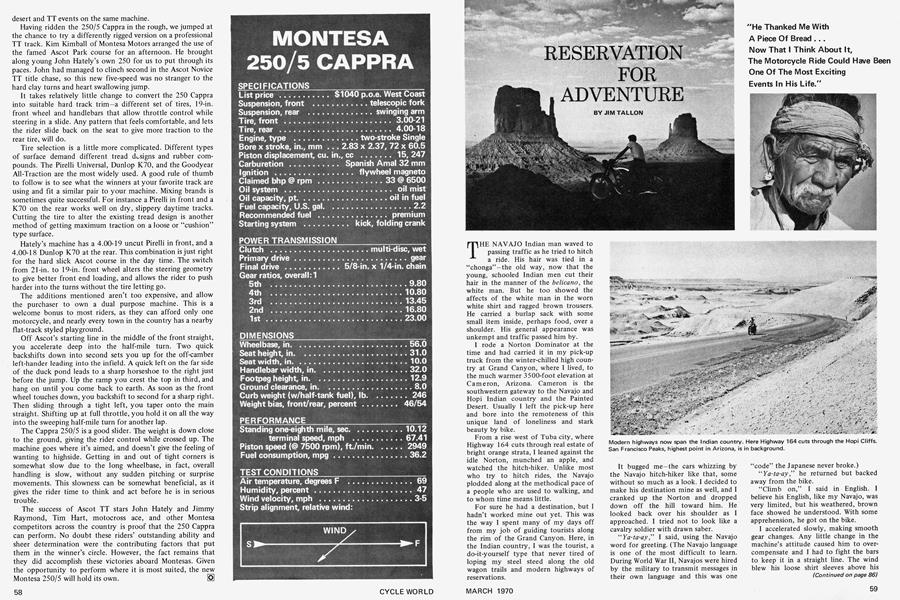

RESERVATION FOR ADVENTURE

JIM TALLON

"He Thanked Me With A Piece Of Bread!.. Now That I Think About It, The Motorcycle Ride Could Have Been One Of The Most Exciting Events In His Life."

THE NAVAJO Indian man waved to passing traffic as he tried to hitch a ride. His hair was tied in a “chonga”—the old way, now that the young, schooled Indian men cut their hair in the manner of the belicano, the white man. But he too showed the affects of the white man in the worn white shirt and ragged brown trousers. He carried a burlap sack with some small item inside, perhaps food, over a shoulder. His general appearance was unkempt and traffic passed him by.

I rode a Norton Dominator at the time and had carried it in my pick-up truck from the winter-chilled high country at Grand Canyon, where I lived, to the much warmer 3500-foot elevation at Cameron, Arizona. Cameron is the southwestern gateway to the Navajo and Hopi Indian country and the Painted Desert. Usually I left the pick-up here and bore into the remoteness of this unique land of loneliness and stark beauty by bike.

From a rise west of Tuba city, where Highway 164 cuts through real estate of bright orange strata, I leaned against the idle Norton, munched an apple, and watched the hitch-hiker. Unlike most who try to hitch rides, the Navajo plodded along at the methodical pace of a people who are used to walking, and to whom time means little.

For sure he had a destination, but I hadn’t worked mine out yet. This was the way I spent many of my days off from my job of guiding tourists along the rim of the Grand Canyon. Here, in the Indian country, I was the tourist, a do-it-yourself type that never tired of loping my steel steed along the old wagon trails and modern highways of reservations.

It bugged me—the cars whizzing by the Navajo hitch-hiker like that, some without so much as a look. I decided to make his destination mine as well, and I cranked up the Norton and dropped down off the hill toward him. He looked back over his shoulder as I approached. I tried not to look like a cavalry soldier with drawn saber.

“Ya-ta-ay” I said, using the Navajo word for greeting. (The Navajo language is one of the most difficult to learn. During World War II, Navajos were hired by the military to transmit messages in their own language and this was one

“code” the Japanese never broke.)

“Ya-ta-ay,” he returned but backed away from the bike.

“Climb on,” I said in English. I believe his English, like my Navajo, was very limited, but his weathered, brown face showed he understood. With some apprehension, he got on the bike.

I accelerated slowly, making smooth gear changes. Any little change in the machine’s attitude caused him to overcompensate and I had to fight the bars to keep it in a straight line. The wind blew his loose shirt sleeves above his elbows and I turned to see forearms of corded muscles just like Indians are supposed to have. I guessed my passenger’s age at 50, but maybe the harsh wind and sun of the Painted Desert caused him to look older than he really was. I grinned at him. Then he began to relax. After ten miles the chonga had blown apart and the store string that tied it in place was gone. His long, black hair whipped about his face and he reminded me of pictures I’d seen of old time Apache warriors. His face split into one of the broadest grins I’ve ever seen on a Navajo.

(Continued on page 86)

Continued from page 59

Then suddenly, he tapped on my back. I turned and he pointed back down the road. At first I thought he had lost something, but after I made a U-turn, he pointed to a side road. We sailed up the wagon road, trailing a horizontal plume of orange desert dust. He leaned with me now, and when we left the ground on a sharp bump he laughed quietly. (I have never heard a Navajo laugh loudly.) After several miles he tapped my back again. Ahead was a hogan (Navajo home of mud and logs), sheep pens, a small empty corral, and other odds and ends usually found around a Navajo camp. Surely he had relatives but no one was there. Probably they had followed their grazing sheep over the distant rock and sand hills.

When he got off the Norton he spoke to me in Navajo, none of which I understood. He opened the burlap sack and brought out a loaf of Navajo fried bread. He broke off two-thirds of it and gave it to me. Navajos do not have a word for “thanks”; they feel saying thanks is not necessary, since it is always understood among the Navajos anyway. He thanked me with the bread. I tore a piece from the center of the loaf and ate it. Then I put the rest in my pack and waved him a farewell. Now that I think about it, the motorcycle ride could have been one of the most exciting events in his life. Perhaps the Norton and I would be mentioned in future Navajo song...who knows.

The incident with the Navajo hitchhiker was but one of the many interesting things that have happened to me in ten years of bike riding in 16,000,000acre Indian country. It’s an easy land to get hooked on, and I got hooked when I saw the John Wayne version of “Stagecoach,” longer back than I like to remember. My first trip took me across primitive, rut slashed, mud roads to Monument Valley and I rode between Agathlan—a jagged volcanic spire rising several thousand feet from the floor of the Valley—and Owl Rock, just like Wayne did. Of course our modes of transportation were quite different, but I feel the motorcycle more practical for seeing the Indian country than any other vehicle—including the horse.

The Indian country offers a broad scenic and adventure spectrum to the average bike rider. Most of its acreage lies in Arizona but laps into New Mexico, Utah and Colorado. Within this confine is the only place in the U.S. where a bike rider can put his front wheel in one state, his back wheel in another, and his feet in a third and fourth at the same time. In addition, the reservations lie in a high desert country, liberally dotted with mesas, bluffs, buttes, prairies, canyons and mountains. A bike rider can expect to find 200-foot high red sand dunes in the vicinity of Red Lake, Arizona, and ponderosa pine country with fine trout lakes in the Chuska Mountains at the Arizona-New Mexico border. He can take his motorcycle right into the heart of the Hopi Indian mesa town of Oraibi, the oldest continually inhabited community in the United States—not St. Augustine, Florida. He’ll rub shoulders with the Navajo at the Indian country’s many trading posts, and he’ll see their herds of sheep and isolated hogans as he motors down both excellent paved roads and lonely back roads.

These nomadic Navajos have increased from about 60,000 in 1952 to about 100,000 today, making them the largest Indian tribe in the U.S. The Hopi tribe stays about the same with a population of some 5000. These pueblo Indians are believed, by many, to be the descendants of the prehistoric people who inhabited the cliff dwellings of Navajo National Monument and Canyon de Chelly.

Back when Highway 164 was unpaved and called “Indian Country 1,” I spotted a small prehistoric Indian ruin under a great overhanging cliff high in the red bluffs of Long House Valley, just west of the road in Marsh Pass. Today the paved highway makes it a lot easier to reach Long House Valley, but it’s also easier to miss seeing the ruin because a rider can travel at much greater speeds. I cut cross-country on my K-Model Harley to find the going better than rutted road. The bike tire tracks I made crossing the sagebrush flats were no doubt the first to be imprinted on this part of the reservation. Near the base of the sandstone bluffs, the K-Model and I wallowed through deep sand to slick rock and then I worked the machine laboriously up a steep incline. Once I stopped to look into an arroyo to see a pool of still water. Handholds had been cut into the rock by prehistoric climbers and I lowered myself to the pool as they had done. I had raised a sweat levering the bike up the grade and now I refreshed myself by splashing cool water on my face and hair.

After that, the real estate became too rough for the machine and I footed up even steeper slick rock to a ledge that had been chiseled out of a near-vertical cliff. This ledge afforded the only entrance to the immense overhang and the ruins within it, ideal for defense. The Navajos call the people who were badgered by raiders into building such dangling cliff towns “The Anasazi,” meaning “the ancient ones.”

Inside the cave, I felt dampness; water seeped into it from a hidden spring. The whole place smelled of yesterday and I could find neither track nor trace of the White Man. Undoubtedly, I was hardly the first to see the ruin, but fierceness of desert winds and weather can obliterate such signs swiftly. I felt a sense of discovery, of being the first bike rider here if nothing else, and a sense of adventure contributed to by the motorcycle. I couldn’t imagine John Wayne riding in a jeep instead of a stagecoach, but for me, adventuring in the Indian country by motorcycle seemed fitting.

I always found the adventure more real, more satisfying by going it alone. On his 77th birthday, Shine Smith—who was probably the greatest missionary to the Navajos that ever lived—told me that after spending most of his life in the Indian country he found a white man was far safer alone here then in a community with his own people. I’ve come to believe it. Both the Navajos and the Hopis have treated me with utmost courtesy, though somewhat reserved. Only once have I ever been dared by a Navajo and he had been drinking and wasn’t on the reservation.

In many places the Indian country is as hard as a pool table and in others my bikes have bogged so deep in dry sand that I’ve had to throttle-walk them for miles. Usually, a strange-sounding Indian name on the Automobile Club of Southern California’s map of the Indian country, or one dropped by a trading post manager or a Navajo or Hopi Indian who worked at Grand Canyon, goaded me into such situations. Once throttle-walking a bike into White Arch at the southern end of White Mesa, just north of Red Lake, my back muscles gave out and I had to hoof it the rest of the way. As a serious amateur photographer I had back-packed a 4 by 5 Speed Graphic to get color scenics of the arch. When I started back across the brush and sand landscape I suddenly realized that it all looked alike. I couldn’t pinpoint exactly where I had left my bike. But I had made tracks in and all I had to do was follow them out. However, a harsh desert wind was quickly filling in my tracks with loose sand. I hunched up, pulled my goggles across my eyes, and leaned into the wind. After zigging and zagging for nearly an hour to find tracks still uncovered, I rested and took a gulp from my canteen. I had always figured myself for one who would panic easily, but here I was, slightly lost and cool as a cucumber. Next time I’d take some better reference points.

As the sun settled near the horizon, I saw several Navajo children with a herd of sheep and decided to ask them if they’d seen a black and chrome motorcycle anywhere in their travels. Had they seen it? They were practically on top of it, and staring at it as if it were an object from another planet. My arrival didn’t lessen their apprehension and they refused to talk with me.

Sometime after dark I still throttlewalked the bike, the headlight pencilling ahead. When I reached hard earth, the bike’s saddle felt soft as a cushion and I felt as if I flew through the desert night.

In the Indian country even little things can have an effect on you. The desert floor was littered with thousands of gleaming gem-like stones. It was petrified wood. The elements had painstakingly broken and scattered the pieces and the angle of the sun reflected light from them as it would from tiny mirrors. There was not a footprint nor a shred of litter to disturb the scene. I picked up several pieces of the petrified wood, then put them back exactly as I had found them, afraid I would disturb the beauty.

While exploring a narrow canyon in the Hopi Cliffs, a sudden August squall blew up and dumped cool rain on me. Since the thermometer cleared 100 degrees, the rain was a pleasure. But I headed hell-bent to get out of that canyon. Before I cleared the entrance, though, a pumpkin-sized boulder dropped with a “ker-plunk” in front of my bike and gave me quite a thrill. Another few feet and I’d have got it on the noggin’. Narrow canyons are no place to be in a storm.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 87

Another time during August, I rode into the Hopi pueblo town of Mishongnovi. The ancient village was crowded with cars, pick-up trucks, horses and wagons. Usually the motorcycle drew a number of Indian spectators, but this time it was only given glances as the brown-skinned people strode toward a court enclosed by stone houses. Something was up; something out of the ordinary.

I moved into the open court with the Indians. Inside I found hundreds more patiently waiting and I glanced around the crowd to see only six more “white eyes” besides myself. In the middle of the court was what the Hopis call a Kisi, a small hut made of grasses. Now I know that I had stumbled onto a famous Hopi Indian snake dance, a ceremonial dance asking the Rain God for moisture for Hopi crops.

Inside the Kisi I knew there to be a basket containing several kinds of snakes, including rattlesnakes. Just outside the hut, several boards had been placed across a three-foot opening in the ground. Suddenly, from one end of the court there was chanting, a deep bass sound that raised the short hair on my neck. About two dozen near-naked men with their bodies smeared with paint moved toward the Kisi. They chanted and danced in a counter-clockwise circle, and each time they passed in front of the Kisi, they stomped on the boards, making a drum-like sound and probably stirring up the snakes just a foot or so away. Then a young Hopi reached into the Kisi and held up a bull snake that writhed around his arm. I glanced up at the other whites standing on the roof of one of the masonary pueblo houses to see they were watching in fixed fascination.

A second snake priest laid one arm across the shoulder of the snake-carrier and tapped the snake on the head with what is called a snake whip, a bundle of eagle feathers tied to a string. The Indians made the counter-clockwise circle again, then released the snake, and though it rushed into the crowd, no one even flinched. The dancers repeated this procedure with other non-poisonous snakes and as they danced some spectators carrying trays of white corn meal threw handfuls of it onto the sweating bodies.

Suddenly I heard the dry rattling sound that nobody ever forgets once he’s heard it. A dancer now held a three-foot rattler aloft. His partner followed his precise foot work in an exacting rhythm and calmed the rattler with the snake whip; they released the snake. Unlike the bull snake earlier, +he buzztail coiled and rattled whenever anyone got near it. Several other rattlers were “danced” and soon crawling snakes littered the court.

By now I sought some sort of escape myself, and wished I were on the roof with the other belicanos. Though a few snakes slithered by my feet, the rattlers preferred the center of the arena. The drums and chanting stopped and the silence was ominous. The Hopis believe that snakes are messengers and the chanting is a plea for vital rain necessary for farming their arid desert land. The snakes are carried back into the desert by runners and released to forward the prayers to the rain god. An elderly but stockily built snake priest indicated the snakes were to be picked up. A man of perhaps 25 shook a snake whip before a rattler and reached behind it. With lightning speed, the snake turned and sank its fangs into the man’s hand between the thumb and forefinger. But he picked up the snake anyway and handed it to another dancer. Unhurried, he walked across the court and into the Kisi, where he remained for several minutes. Some white men who know the Hopis well say they take a potion prior to the dance that the Indians believe makes them immune to rattlesnake venom. The Indians have also been accused of “milking” the snakes of their poison before the dance, and some have suggested they even take antivenom. I don’t know what the young Hopi snake priest did inside the Kisi, but I do know that he returned to the gathering of the snakes very calmly and there was no swelling of his hand.

The fact a dancer had been bitten had no effect on the courage of the others. One man reached for another rattler and the elderly snake priest stopped him and pointed to a boy of 10 or 12 years of age. The boy, using a snake whip, safely picked up a two-foot rattler and several non-poisonous snakes and ran from the court. A number of boys participated in the ceremony since this is part of their initiation into the Snake Clan.

I remember a story a white schoolmarm teaching on the Hopi Reservation told me about one of her young students. One day the boy didn’t report to class, and after several days absence she went to his family to find out why. They told her nothing. But on her way back she walked through the nearby graveyard on a hunch and saw the boy’s blanket on a grave. After several weeks of prying she learned during initiation practices of the Snake Clan, the boy had been bitten by a rattler and died. For a long time she was up in arms at the Snake Clan, but I doubt very much if it had any effect whatsoever on their practices.

When I topped off the steep road leaving Mishongnovi, some of the runners were returning from releasing the snakes. Their faces were devout just as the faces watching the snake dance had been. These pueblo farmers were just as serious about their religion as people of the “outside world” were about theirs.

Back at Grand Canyon I talked about my exploits in the Indian country. An unbelieving muleskinnner who took pack groups into the Canyon doubted the motorcycle’s maneuverability offroad.

“I’ll take that bike places you’ll never get a mule to go,” I bragged.

The ’skinner got a little hot under the collar and said he’d give me some odds on that. Fortunately for him the test never came off. He would have lost for sure. You see, I had a mine shaft picked out that an average guy has to stoop to walk into. Trying to get a mule to crawl into that black hole would be about as easy as trying to drag the critter through a knot-hole by his tail. I had another trick up my sleeve. I intended to stick my feet over the bike’s license plate and, lying flat on the tank, ride it under a hitching rail. That would be another crawling experience—for the muleskinner who tried to make his mule lie down and wiggle under the rail.

The Indian country is still out there— all 16,000,000 acres of it. Outside of a few paved highways now, there’s been little change since I first put bike tracks on it. The spectacular scenery is magnetic and the Navajos and Hopis still look at bikes as foreign to their world. The snake dance is still held in August and the Hopis permit white visitors. But cameras are strictly taboo and subject to being smashed on a rock. There are still thousands of miles of wagon roads and trails untouched by the wheels of a motorcycle.

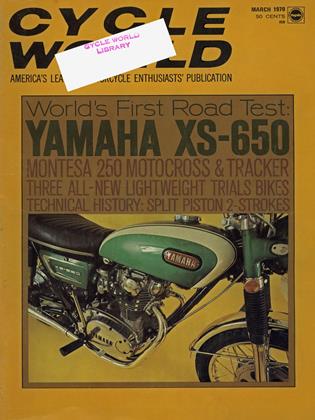

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

March 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

March 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1970 -

Features

FeaturesDoes Your Club Owe Income Tax?

March 1970 By Robert O. Fee -

Competition

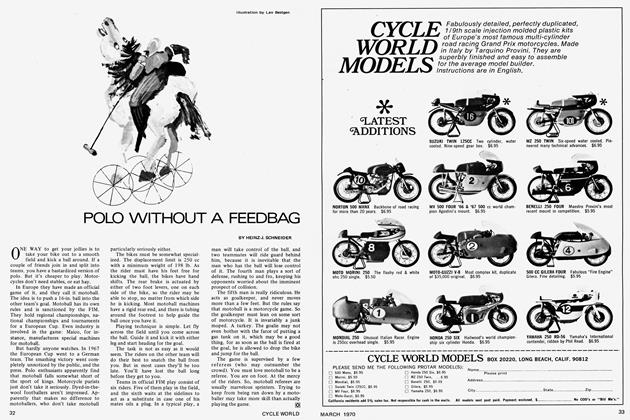

CompetitionPolo Without A Feedbag

March 1970 By Heinz-J. Schneider -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

March 1970 By John Dunn