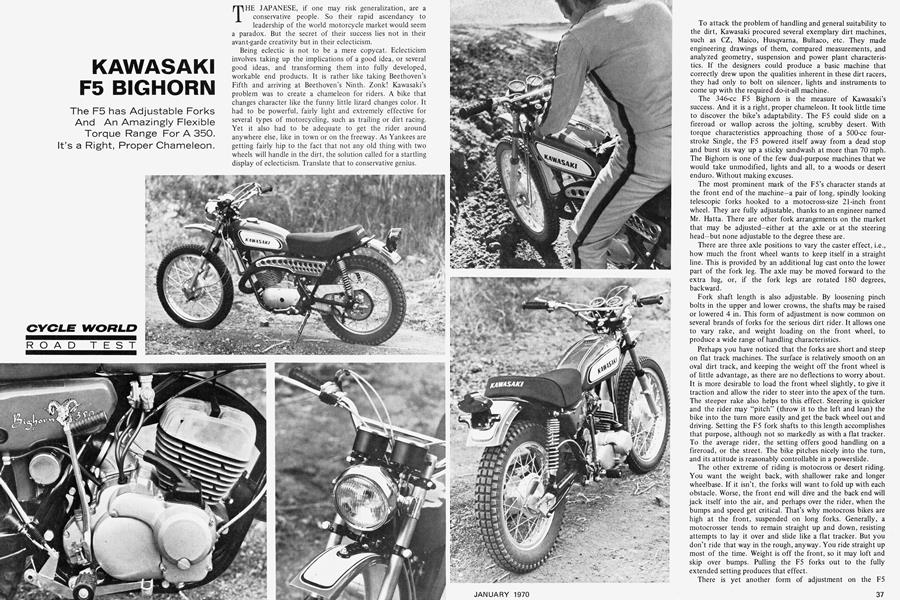

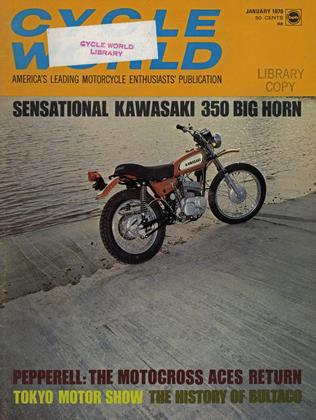

KAWASAKI F5 BIGHORN

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The F5 has Adjustable Forks And An Amazingly Flexible Torque Range For A 350. It's a Right, Proper Chameleon.

THE JAPANESE, if one may risk generalization, are a conservative people. So their rapid ascendancy to leadership of the world motorcycle market would seem a paradox. But the secret of their success lies not in their avant-garde creativity but in their eclecticism.

Being eclectic is not to be a mere copycat. Eclecticism involves taking up the implications of a good idea, or several good ideas, and transforming them into fully developed, workable end products. It is rather like taking Beethoven’s Fifth and arriving at Beethoven’s Ninth. Zonk! Kawasaki’s problem was to create a chameleon for riders. A bike that changes character like the funny little lizard changes color. It had to be powerful, fairly light and extremely effective for several types of motorcycling, such as trailing or dirt racing. Yet it also had to be adequate to get the rider around anywhere else, like in town or on the freeway. As Yankees are getting fairly hip to the fact that not any old thing with two wheels will handle in the dirt, the solution called for a startling display of eclecticism. Translate that to conservative genius.

To attack the problem of handling and general suitability to the dirt, Kawasaki procured several exemplary dirt machines, such as CZ, Maico, Husqvarna, Bultaco, etc. They made engineering drawings of them, compared measurements, and analyzed geometry, suspension and power plant characteristics. If the designers could produce a basic machine that correctly drew upon the qualities inherent in these dirt racers, they had only to bolt on silencer, lights and instruments to come up with the required do-it-all machine.

The 346-cc F5 Bighorn is the measure of Kawasaki’s success. And it is a right, proper chameleon. It took little time to discover the bike’s adaptability. The F5 could slide on a fireroad or wallop across the jolting, scrubby desert. With torque characteristics approaching those of a 500-cc fourstroke Single, the F5 powered itself away from a dead stop and burst its way up a sticky sandwash at more than 70 mph. The Bighorn is one of the few dual-purpose machines that we would take unmodified, lights and all, to a woods or desert enduro. Without making excuses.

The most prominent mark of the F5’s character stands at the front end of the machine—a pair of long, spindly looking telescopic forks hooked to a motocross-size 21-inch front wheel. They are fully adjustable, thanks to an engineer named Mr. Hatta. There are other fork arrangements on the market that may be adjusted—either at the axle or at the steering head—but none adjustable to the degree these are.

There are three axle positions to vary the caster effect, i.e., how much the front wheel wants to keep itself in a straight line. This is provided by an additional lug cast onto the lower part of the fork leg. The axle may be moved forward to the extra lug, or, if the fork legs are rotated 180 degrees, backward.

Fork shaft length is also adjustable. By loosening pinch bolts in the upper and lower crowns, the shafts may be raised or lowered 4 in. This form of adjustment is now common on several brands of forks for the serious dirt rider. It allows one to vary rake, and weight loading on the front wheel, to produce a wide range of handling characteristics.

Perhaps you have noticed that the forks are short and steep on flat track machines. The surface is relatively smooth on an oval dirt track, and keeping the weight off the front wheel is of little advantage, as there are no deflections to worry about. It is more desirable to load the front wheel slightly, to give it traction and allow the rider to steer into the apex of the turn. The steeper rake also helps to this effect. Steering is quicker and the rider may “pitch” (throw it to the left and lean) the bike into the turn more easily and get the back wheel out and driving. Setting the F5 fork shafts to this length accomplishes that purpose, although not so markedly as with a flat tracker. To the average rider, the setting offers good handling on a fireroad, or the street. The bike pitches nicely into the turn, and its attitude is reasonably controllable in a powerslide.

The other extreme of riding is motocross or desert riding. You want the weight back, with shallower rake and longer wheelbase. If it isn’t, the forks will want to fold up with each obstacle. Worse, the front end will dive and the back end will jack itself into the air, and perhaps over the rider, when the bumps and speed get critical. That’s why motocross bikes are high at the front, suspended on long forks. Generally, a motocrosser tends to remain straight up and down, resisting attempts to lay it over and slide like a flat tracker. But you don’t ride that way in the rough, anyway. You ride straight up most of the time. Weight is off the front, so it may loft and skip over bumps. Pulling the F5 forks out to the fully extended setting produces that effect.

There is yet another form of adjustment on the F5

forks-spring tension. You can change the springs in any forks to produce varying resistance to deflection, but the F5 fork tension may be changed without swapping springs. This three-way fork spring preload is made possible by a cam-type adjuster located inside the top fork shaft nut. Remove a small rubber plug, and turn the slotted adjuster to soft, medium or hard settings. Different weight oils may be tried with any of the previously mentioned settings to give the rider a fork that will suit any surface or situation. It should not be overlooked that these forks offer long travel and excellent damping both ways, with no clunking on full rebound.

One note, with the forks in a fully extended position, installation of a “U” type fork brace is necessary, as the long legs, unstiffened, will flex considerably, causing front wheel wiggle. This eventuality has been foreseen, as lugs are cast into the fork legs in just the right position for proper mounting.

While the Hatta forks are a remarkable innovation, the basic considerations that make the Kawasaki Bighorn appropriate to the dirt merit discussion. The evolution of the dirt machine, particularly in international motocross competition, graphically illustrates what these considerations are: light weight, compactness, strength, usable (or tractable) power and that elusive quality called “handling.”

The light weight and compactness are dictated by the rider’s dimensions. A man works against his machine, an animate sizable mass of weight, and one must assume that the greater advantage a rider has in terms of his own weight and the maneuverability of what he is straddling, the greater will be his control over the machine. Why one needs horsepower and strength (crash resistance) is self-explanatory.

As Kawasaki had neither the big-bore engine nor the appropriate frame for it, they had to start from scratch. To make the motorcycle light and compact, one must begin with an engine that will allow those dimensions, which in the F5’s case is a 346-cc two-stroke Single with unit five-speed gearbox. That displacement range lends itself to a generous power output, yet is small enough to allow a compromise with the need for minimum size and weight.

All-alloy construction of the cases, cylinder and head have held the weight to a minimum. Conventional two-stroke porting with five transfer ports, retains the stump pulling torque necessary in an all-around dual-purpose machine. The rotary valve has mild timing, contributing to the engine’s willingness to pull at low rpm.

To keep engine width as narrow as possible, a wafer thin hardened steel rotary valve is used. Kawasaki engineers have done an admirable job of engine design. As the carburetor on a rotary valve engine must protrude from the side, it’s amazing just how narrow the unit is. The carburetor cavity is completely airtight, except for the incoming fresh air from the air filter. A one-way diaphragm pump at the front of the crankcase allows accumulations of excess fuel to clear from the cavity.

Two spark plug holes are tapped into the alloy cylinderhead. That second hole may carry a second sparkplug or an optional compression release. The cylinder barrel has a cast iron liner that may be bored to accept oversize pistons after excessive use has opened up the clearances. The three-ring piston is made of aluminum alloy that expands at the same rate as the cylinder, allowing tolerances to remain the same throughout the operating range. The head is connected to the cylinder by four studs that originate in the crankcases. Four additional bolts pass through the head into the top of the cylinder. This evens the pressure at the joint, and allows the use of a thin copper gasket.

The crankshaft assembly is a pressed-together unit, with

large ball bearings on both main shafts, and rollers on the big end of the rod. A needle bearing running on a hard chrome-steel wrist pin is used in the small end. Aluminum crankcases, split vertically, are held together by a variety of studs and screws running through the cases for additional strength.

The transmission cavity is part of the unit-construction crankcase casting, and features five speeds. A constant mesh gear train runs on ball and roller bearings on both input and output shafts. Shifting is smooth and positive, although rushing the shift lever would produce an unwanted neutral occasionally. The pattern is down for low, and up for the rest, with neutral between low and second.

Deserving special mention is the hefty clutch, a multi-disc wet unit, with seven fiber plates and eight metal ones. It nicely withstood the rigors of repeated slogging and several attempts up the “Impossible Trail” at Saddleback Park. Shift lever position, incidentally, is also “adjustable.” It may be switched from the left side, which is standard, to the right, as the shift shaft protrudes from both sides of the cases. A brake lever and cable conversion kit will be available from dealers.

The ignition is an advanced version of the capacitive discharge system introduced on the Mach III last year. Starting was never a problem. After a few strong kicks, the F5 would light off. A feature that we liked is the thumb-operated starting lever. This little lever, located by the throttle, enriches the mixture when depressed, and eases the starting drill. The spark plug is of the surface gap variety necessary for the CD ignition. Plug life is greatly prolonged for a two-stroke, and fouling is practically nonexistent.

Fuel is supplied by an altitude compensating Mikuni with a 32-mm throat diameter. The main jet can be changed by removing a threaded plug on the outside of the carburetor cavity cover. Feed from the oil-injection pump is controlled by a cable connected to the throttle twistgrip. Fresh lubricating oil is force-fed into the fuel intake tract and direct to the crankshaft main bearings.

For those who demand more power, an optional “PowerPak” performance kit will be made available through Kawasaki dealers. This kit gives the Bighorn a claimed 45 horsepower! It consists of an expansion chamber exhaust, different cylinder, higher compression head, and a racing-type, forged piston. With the “Power-Pak” installed, a loss in low rpm torque will be felt. The easy-to-handle low end power of the stock machine is one of the things CYCLE WORLD staffers liked best about the Bighorn. It’s more than enough to give even the most demanding rider an enjoyable ride, be it on the freeway or out in the boondocks.

Kawasaki’s all-new frame for the F5 is simple in design and seems quite strong, although it is light and tube members are of small diameter. It affords just enough space to mount the engine unit and necessary pieces.

Duplex downtubes run from the steering head under the engine cases and back up to connect with double top backbone tubes. A large diameter tube strut links the backbone with the upper end of the steering head. Flat steel plates welded to the frame tubes form a wide pivot point for the swinging arm attachment. This eliminates most of the twist found in a narrow pivot point and is a major factor in the Bighorn’s stable handling. Auxiliary tubes welded to the main

eradle form triangles which provide additional rigidity.

A stout tubular swinging arm is suspended from the triangulated rear section of the frame by a pair of 4-in. travel dampers. Constant rate springs control compression, while oil-fed internal passages dampen the rebound. These damper units are similar to the popular Maverick units used on many dirt machines. Here again the ingenious Mr. Hatta had a hand in things, as he matched the rear dampers’ rates to those of the front forks, giving a “tuned” suspension front and rear.

Alloy rims are utilized for the wheels, with trials pattern tires. The front is a 3.00-21, and the rear a 4.00-18. While the rims are a trifle soft for really rough going and suffered some minor dents as we pounded about, their advantage in lower unsprung weight is well worthwhile. Both front and rear alloy hubs have cast-in 6-in. iron brake drums. The hubs are both light and strong, having an equal length spoke pattern and extra ribs to strengthen critical areas. The wide mounting base for the two rows of spokes on the rear wheel hub indicates just how sophisticated Mr. Hatta has become in regard to the problems of dirt riding. By spreading the spoke rows apart at the hub, you increase triangulation, strenghtening the wheel’s resistance to pounding, and to lateral deflection, with a gain in reliability, and perhaps a minor benefit in handling.

Both wheels are of the quick change type, with one-piece pull-through axles for easy removal. The rear sprocket is a bolt-on aluminum unit of 40 teeth, driven by a large 3/8by 5/8-in. roller chain. The wheels, as well as the Hatta forks and rear dampers, will be available to parts customers for use on other makes.

Considering the good stopping power of the brake units, necessary for the street-oriented rider, it is a pleasant surprise that they are quite controllable, and subject neither to shudder or inadvertent lock-up. And they are waterproof, too.

Front and rear fenders are alloy with painted finish. The front one is mounted high, which is both stylish and functional, should the rider encounter sticky mud (which could clog the front wheel if adequate clearance were not provided). The rear fender affords ample clearance, and has an inner shield attached to add strength and provide protection for the taillight wires. All the auxiliary pieces held together during the test. This speaks well for Kawasaki’s method of attachment. Only two small screws that hold the heat shield to the exhaust system fell out during testing. We were assured that this was being changed on future models; a washer under the screws will solve the problem.

The seat, covered with an anti-slip covering, is quite comfortable. It is three-quarter length, with enough room for two, providing the passenger is sufficiently slim. No passenger footrests are provided, so we can assume the seat is intended for solo use. The handlebars are curved so that they may be rotated to fit riders with different arm lengths. We found them rather narrow for the dirt. Footpegs have been given the same treatment, and may be set in a variety of positions.

Fuel capacity is ample at 3 gal. The tank is attractively styled and narrow at the back, affording a slim fit for the rider’s legs. Head and taillights are easily detachable, adding to the quick-change ability of the Bighorn. The individual tachometer and speedometer units are rubber-mounted to ensure a minimum amount of vibration transfer, and may also be removed quickly.

In the F5, Kawasaki has designed a machine with the American rider in mind. It is fully adjustable to meet his day-to-day whims, and powerful enough to meet one of his major preoccupations—performance. We would not hesitate to recommend the F5 to both the novice and the expert, for it will satisfy both. \0\

KAWASAKI

F5 BIGHORN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments:

Departments:Round Up

January 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments:

Departments:The Service Department

January 1970 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1970 -

Departments:

Departments:The Scene

January 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features:

Features:Tokyo Motor Show

January 1970 By Byron Black -

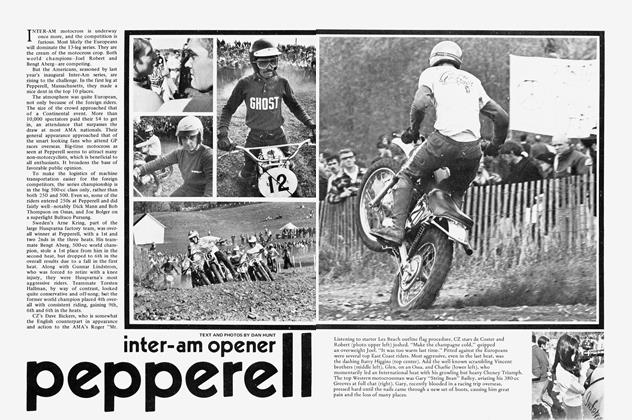

Competition:

Competition:Inter-Am Opener Pepperell

January 1970