REPORT FROM ITALY

CARLO PERELLI

VALLI BERGAMASCHE

Bad weather and politics burdened the 21st Valli Bergamasche (Bergamo Valley), one of the most famous and difficult ISDT-type trials of the world. Rain, wind and even snow nullified the advantages of a cut in the course’s length and the emergency schedule adopted by the international jury— Bergamasche was as tough as ever.

Then, the 14 East German riders didn’t appear at the second day’s start as a protest against their nation not being “properly” recognized by the organizers. This is a typical, nasty case of politics invading the sporting field. Italy, like the other NATO countries, doesn’t recognize East Germany, so the Italian authorities ordered the organizing Moto Club of Bergamo not to identify the East German riders by country. In an attempt to avoid the predicament, the organizers referred to all riders by the titles of their federations. But this didn’t satisfy the East German contingent, who abandoned the field. The gesture cost them some excellent positions. At the end of the first day, MZ was leading the manufacturers’ team contest, while eight East German riders had gold medallist standings.

Bergamasche was the fifth round of the newly introduced European Trials Championship (the West and East German, Austrian and Czechoslovakian rounds have been held, and the last will be in Spain). In conforming with the series’ rules, the Valli Bergamasche lost some of its unique features, such as its three-day duration with two loops each day.

The course included terrain used in previous Bergamasche trials, as well as last year’s ISDT, run in the same area. The first day’s 146-mile section was the more difficult; of 126 starters from eight countries, the cream of the specialists with the best machines, 36 retired and only 43 retained “clean sheets.” The second day (145.7 miles) was more merciful—11 retired and just two more lost their gold medals. The number of gold medallists dropped to 33 following the withdrawal of the East Germans. Five silver medals and 26 bronze were awarded among 64 finishers.

Favored by mechanical superiority and abundant practice in the wet and mud, the German, Austrian and Czechoslovakian riders dominated the special tests. Thus, the home riders did not pick up many bonus points.

Best machines again were Zundapp and Puch in the lightweight classes (the Austrian bikes now slightly superior to the German), and Jawa and MZ in the larger displacement classes. All are orthodox two-strokes.

With only two speed schedules (24 mph for up to 75-cc bikes and 25 mph for those over 75 cc) and bad weather, the larger bikes had an advantage. First overall were the over 350-cc and 350-cc class exponents, while the 75and 50-cc class riders struggled at the other end of the scale.

Absolute winner was West German Erwin Schmieder (Jawa 400). Class winners were Czechoslovakians Masita (350) and Rabas (250), both Jawa mounted; Austrians Leitgeb (175) and Witthoft (125), both on Puch; and West Germans Specht (100), Brandi (75) and Brinkmann (50), the famous Zundapp trio.

Best Italian and best four-stroke representative was Romualdo Consonni, who prepared his 441 BSA Victor himself. Consonni also was a member of the victorious Moto Club Bergamo team, along with Dossena (Morini 125) and Foresti (Gilera 175). Puch won the factory team contest ahead of Zundapp and Jawa.

Present leaders of the European Trials Championship, and likely to remain so after the Spanish round, are Schmieder (Jawa 400), Masita (Jawa 350), Mrazek (Jawa 250), Leitgeb (Puch 175), Witthoft (Puch 125), Kramer (Zundapp 100), Brandi (Zundapp 75) and Dietrich (Puch 50).

THE V7 SPECIAL

Deliveries are imminent, at home and abroad, of the 760 Moto Guzzi V7 Special, which, say the Mandello del Lario factory executives, will not supersede the standard V7.

Externally, modifications are visible in the battery case (which now extends to the air filter), in the concentric type Dellorto carburetors, in the easier to operate central stand and in the welcome addition of the rev counter, separate from the speedometer and positioned with it above the headlamp. Less visible, but no less interesting, the starting button now is comfortably placed near the throttle twistgrip. The carburetors feature an acceleration pump for feeding under hard, sudden openings.

Inside, there is a larger bore (83 mm instead of 80). Overall ratios have been slightly lengthened (two teeth less at the rear sprocket), as well as the third and fourth gear ratios. With a 6300-rpm limit, the V7 Special can top 114 mph. Factory testers report a 14-sec. standing start quarter mile.

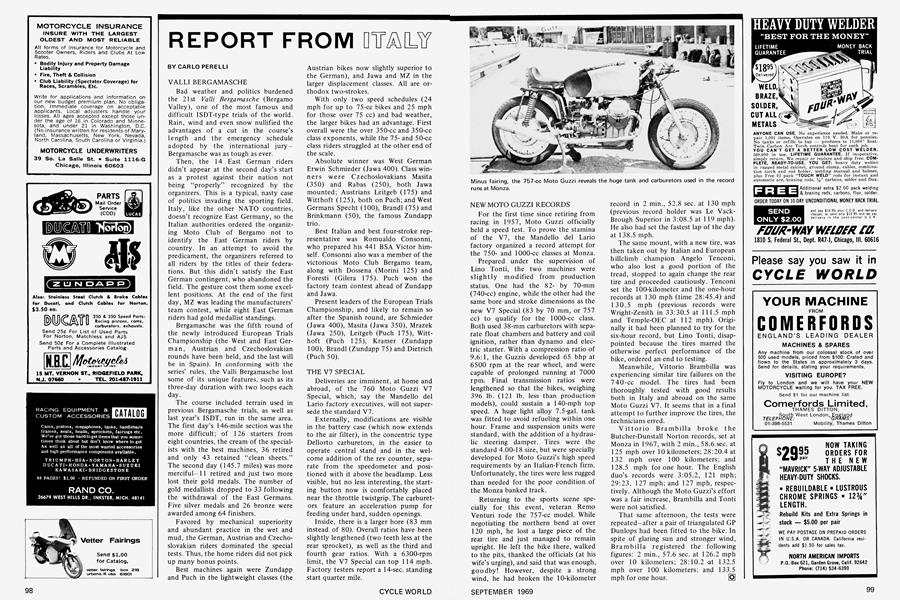

NEW MOTO GUZZI RECORDS

For the first time since retiring from racing in 1957, Moto Guzzi officially held a speed test. To prove the stamina of the V7, the Mandello del Lario factory organized a record attempt for the 750and 1000-cc classes at Monza.

Prepared under the supervision of Lino Tonti, the two machines were slightly modified from production status. One had the 82by 70-mm (740-cc) engine, while the other had the same bore and stroke dimensions as the new V7 Special (83 by 70 mm, or 757 cc) to qualify for the 1000-cc class. Both used 38-mm carburetors with separate float chambers and battery and coil ignition, rather than dynamo and electric starter. With a compression ratio of 9.6:1, the Guzzis developed 65 bhp at 6500 rpm at the rear wheel, and were capable of prolonged running at 7000 rpm. Final transmission ratios were lengthened so that the bikes, weighing 396 lb. (121 lb. less than production models), could sustain a 140-mph top speed. A huge light alloy 7.5-gal. tank was fitted to avoid refueling within one hour. Frame and suspension units were standard, with the addition of a hydraulic steering damper. Tires were the standard 4.00-18 size, but were specially developed for Moto Guzzi’s high speed requirements by an Italian-French firm. Unfortunately, the tires were less rugged than needed for the poor condition of the Monza banked track.

Returning to the sports scene specially for this event, veteran Remo Venturi rode the 757-cc model. While negotiating the northern bend at over 120 mph, he lost a large piece of the rear tire and just managed to remain upright. He left the bike there, walked to the pits, thanked the officials (at his wife’s urging), and said that was enough, goodby! However, despite a strong wind, he had broken the 10-kilometer

record in 2 min., 52.8 sec. at 130 mph (previous record holder was Le VackBrough Superior in 3:08.5 at 119 mph). He also had set the fastest lap of the day at 138.5 mph.

The same mount, with a new tire, was then taken out by Italian and European hillclimb champion Angelo Tenconi, who also lost a good portion of the tread, stopped to again change the rear tire and proceeded cautiously. Tenconi set the 100-kilometer and the one-hour records at 130 mph (time 28:45.4) and

130.5 mph (previous records were Wright-Zenith in 33:30.5 at 111.5 mph and Temple-OEC at 112 mph). Originally it had been planned to try for the six-hour record, but Lino Tonti, disappointed because the tires marred the otherwise perfect performance of the bike, ordered an end to testing.

Meanwhile, Vittorio Brambilla was experiencing similar tire failures on the 7 40-cc model. The tires had been thoroughly tested with good results both in Italy and abroad on the same Moto Guzzi V7. It seems that in a final attempt to further improve the tires, the technicians erred.

Vittorio Brambilla broke the Butcher-Dunstall Norton records, set at Monza in 1967, with 2 min., 58.6 sec. at 125 mph over 10 kilometers; 28:20.4 at 132 mph over 100 kilometers; and

128.5 mph for one hour. The English duo’s records were 3:05.2, 121 mph; 29:23, 127 mph; and 127 mph, respectively. Although the Moto Guzzi’s effort was a fair increase, Brambilla and Tonti were not satisfied.

That same afternoon, the tests were repeated-after a pair of triangulated GP Dunlops had been fitted to the bike. In spite of glaring sun and stronger wind, Brambilla registered the following figures: 2 min., 57.6 sec. at 126.2 mph over 10 kilometers; 28:10.2 -at 132.5 mph over 100 kilometers; and 133.5 mph for one hour.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

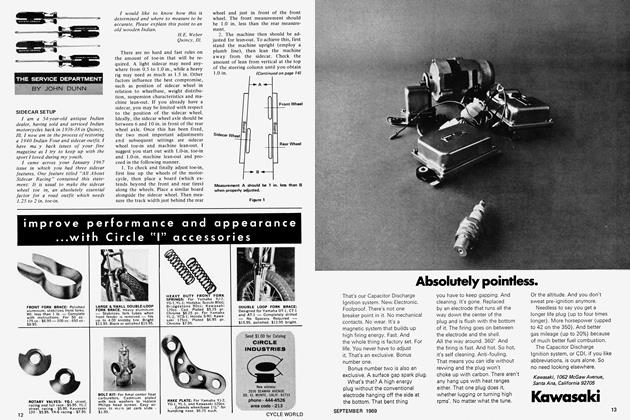

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1969 -

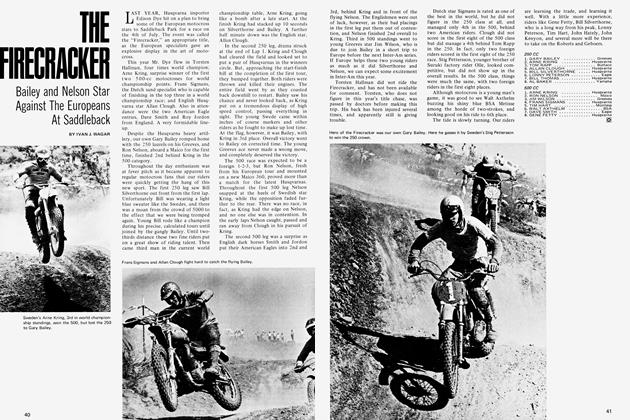

Competition

CompetitionThe Firecracker

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

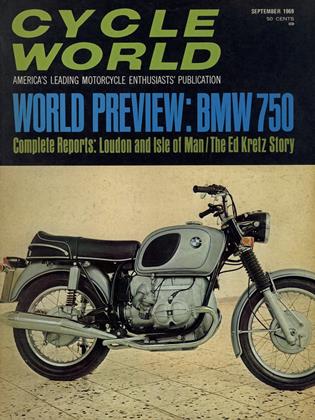

Preview

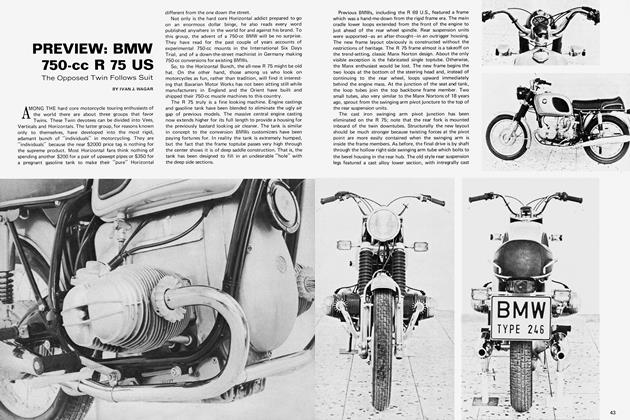

PreviewBmw 750-Cc R 75 Us

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar