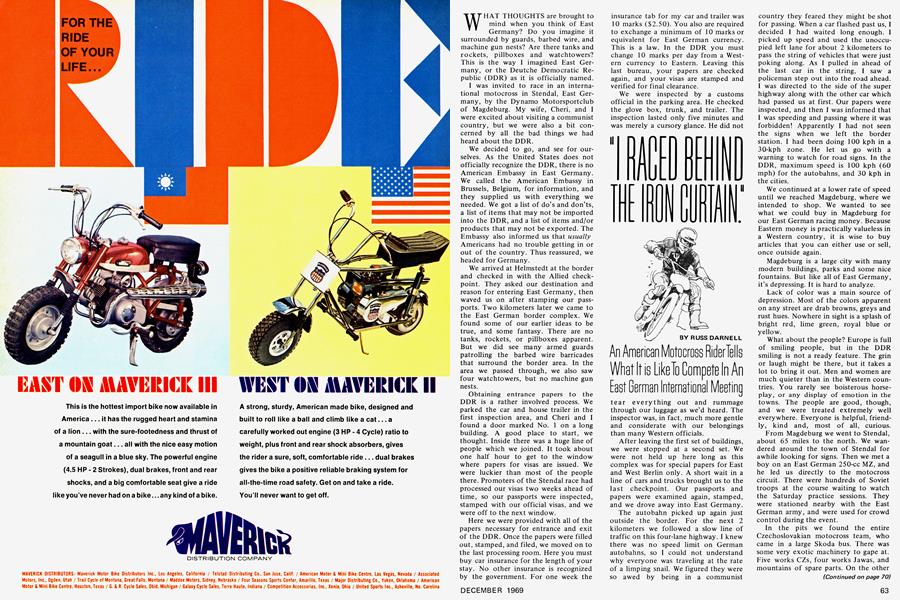

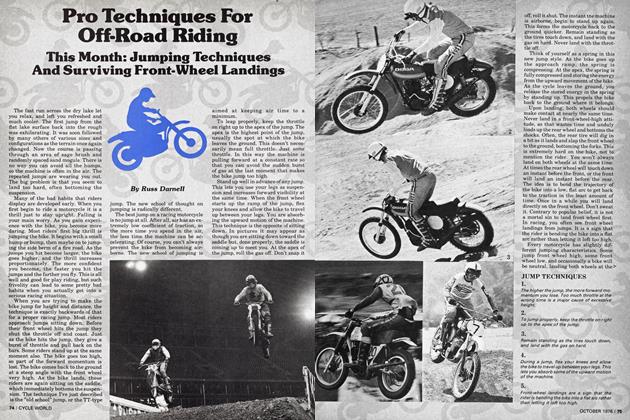

"I RACED BEHIND THE IRON CURTAIN."

An American Motocross Rider Tells What It is Like To Compete In An East German International Meeting

RUSS DARNELL

WHAT THOUGHTS are brought to mind when you think of East Germany? Do you imagine it surrounded by guards, barbed wire, and machine gun nests? Are there tanks and rockets, piliboxes and watchtowers? This is the way I imagined East Germany, or the Deutche Democratic Republic (DDR) as it is officially named.

I was invited to race in an international motocross in Stendal, East Germany, by the Dynamo Motorsportclub of Magdeburg. My wife, Chéri, and I were excited about visiting a communist country, but we were also a bit concern-ed by all the bad things we had heard about the DDR.

We decided to go, and see for ourselves. As the United States does not officially recognize the DDR, there is no American Embassy in East Germany. We called the American Embassy in Brussels, Belgium, for information, and they supplied us with everything we needed. We got a list of do’s and don’ts, a list of items that may not be imported into the DDR, and a list of items and/or products that may not be exported. The Embassy also informed us that usually Americans had no trouble getting in or out of the country. Thus reassured, we headed for Germany.

We arrived at Helmstedt at the border and checked in with the Allied checkpoint. They asked our destination and reason for entering East Germany, then waved us on after stamping our passports. Two kilometers later we came to the East German border complex. We found some of our earlier ideas to be true, and some fantasy. There are no tanks, rockets, or pillboxes apparent. But we did see many armed guards patrolling the barbed wire barricades that surround the border area. In the area we passed through, we also saw four watchtowers, but no machine gun nests.

Obtaining entrance papers to the DDR is a rather involved process. We parked the car and house trailer in the first inspection area, and Chéri and I found a door marked No. 1 on a long building. A good place to start, we thought. Inside there was a huge line of people which we joined. It took about one half hour to get to the window where papers for visas are issued. We were luckier than most of the people there. Promoters of the Stendal race had processed our visas two weeks ahead of time, so our passports were inspected, stamped with our official visas, and we were off to the next window.

Here we were provided with all of the papers necessary for entrance and exit of the DDR. Once the papers were filled out, stamped, and filed, we moved on to the last processing room. Here you must buy car insurance for the length of your stay. No other insurance is recognized by the government. For one week the insurance tab for my car and trailer was 10 marks ($2.50). You also are required to exchange a minimum of 10 marks or equivalent for East German currency. This is a law. In the DDR you must change 10 marks per day from a Western currency to Eastern. Leaving this last bureau, your papers are checked again, and your visas are stamped and verified for final clearance.

We were inspected by a customs official in the parking area. He checked the glove box, trunk, and trailer. The inspection lasted only five minutes and was merely a cursory glance. He did not

tear everything out and rummage through our luggage as we’d heard. The inspector was, in fact, much more gentle and considerate with our belongings than many Western officials.

After leaving the first set of buildings, we were stopped at a second set. We were not held up here long as this complex was for special papers for East and West Berlin only. A short wait in a line of cars and trucks brought us to the last checkpoint. Our passports and papers were examined again, stamped, and we drove away into East Germany.

The autobahn picked up again just outside the border. For the next 2 kilometers we followed a slow line of traffic on this four-lane highway. I knew there was no speed limit on German autobahns, so I could not understand why everyone was traveling at the rate of a limping snail. We figured they were so awed by being in a communist country they feared they might be shot for passing. When a car flashed past us, I decided I had waited long enough. I picked up speed and used the unoccupied left lane for about 2 kilometers to pass the string of vehicles that were just poking along. As I pulled in ahead of the last car in the string, I saw a policeman step out into the road ahead. I was directed to the side of the super highway along with the other car which had passed us at first. Our papers were inspected, and then I was informed that I was speeding and passing where it was forbidden! Apparently I had not seen the signs when we left the border station. I had been doing 100 kph in a 30-kph zone. He let us go with a warning to watch for road signs. In the DDR, maximum speed is 100 kph (60 mph) for the autobahns, and 30 kph in the cities.

We continued at a lower rate of speed until we reached Magdeburg, where we intended to shop. We wanted to see what we could buy in Magdeburg for our East German racing money. Because Eastern money is practically valueless in a Western country, it is wise to buy articles that you can either use or sell, once outside again.

Magdeburg is a large city with many modern buildings, parks and some nice fountains. But like all of East Germany, it’s depressing. It is hard to analyze.

Lack of color was a main source of depression. Most of the colors apparent on any street are drab browns, greys and rust hues. Nowhere in sight is a splash of bright red, lime green, royal blue or yellow.

What about the people? Europe is full of smiling people, but in the DDR smiling is not a ready feature. The grin or laugh might be there, but it takes a lot to bring it out. Men and women are much quieter than in the Western countries. You rarely see boisterous horseplay, or any display of emotion in the towns. The people are good, though, and we were treated extremely well everywhere. Everyone is helpful, friendly, kind and, most of all, curious.

From Magdeburg we went to Stendal, about 65 miles to the north. We wandered around the town of Stendal for awhile looking for signs. Then we met a boy on an East German 250-cc MZ, and he led us directly to the motocross circuit. There were hundreds of Soviet troops at the course waiting to watch the Saturday practice sessions. They were stationed nearby with the East German army, and were used for crowd control during the event.

In the pits we found the entire Czechoslovakian motocross team, who came in a large Skoda bus. There was some very exotic machinery to gape at. Five works CZs, four works Jawas, and mountains of spare parts. On the other side of the pits were the East German riders, and some juniors who were to ride the fill-in races on Sunday. I had one of the few Husqvarnas. The other Huskies belonged to Wilke Adolphson, Sweden, and Gerrit Wollsink, Holland.

(Continued on page 70)

IRON CURTAIN MOTO-CROSS

Continued from page 63

The course was one of the best I have ever ridden. It had a perfect mixture of all types of riding. Sand, trees, mud, twisty sections, fast straight, jumps, uphills, downhills, and even two speedway corners where you really had to get all hung out. I learned the course by walking around and watching the Czech team practice, riding aggressively even though it was only a practice session.

Next morning we awoke to the sound of someone pounding on the door of our caravan. It was the president and secretary of the sponsoring club. They had brought a bouquet of roses and a present for my wife for her birthday. They got the birth date information from our visa applications. Later, after breakfast, another of the club officials brought her some candy, more flowers and a basket of fresh cherries. A very good way to start the day.

Before practice each rider must have his bike inspected by a technical committee, sign a waiver of liability, and get a minor physical examination from a doctor at the circuit. Starting positions were determined by a timed five-lap practice run. Whoever had the fastest time got to choose the best starting position. Second fastest had second choice and so on.

I felt on form in practice, and found that I was able to pass most of the riders without much effort. At the end of practice, the president of the technical committee informed me that I was first to choose my start position at race time. That meant that I had fastest recorded time, which was very pleasing indeed.

Between practice and the first race there was a two-hour pause. During this pause we had many visitors, some who could speak a little English, but most could not. The ones who could, acted as translators for the others.

We learned much about the everyday life and problems in the DDR through talking with the people. Purchasing a car is a big problem, for instance. There are only three brands of cars the East Germans have access to buy: the Skoda (Czech), Wartburg (Russian) and the Trabant (DDR). All three are small, cheaply made, and of poor quality. Delivery on a new car takes from seven to nine years!

Before the first international event, there was the usual presentation of riders and parade, common to European motocross, a gala affair, serving to build up pre-race excitement. All the international riders (there were 52 of us), marched out across the huge starting area accompanied by a parade of miniskirted girls and a band. The girls were paired and each pair carried a national flag, with the competitors lining up behind their respective colors. When the parade stopped in front of the huge crowd, a German official read a speech, and the East German anthem was played. With the preliminaries over, it was on to the race!

I was let out to the start area first, and I picked what I thought would be the best position on the line. The start line quickly filled up with the 5 1 other riders. I had never been to an international event with so many starters. The start method was of the clutch engaged and dropped flag variety. This system is rarely seen in Western European races; most clubs have switched to the metal start gate.

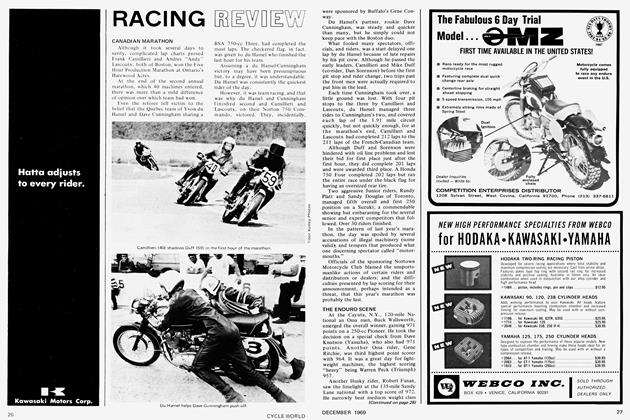

The first right-hand corner was pretty hairy as 52 of us stormed into it. Dieter Kley (DDR) on a 400 CZ took the lead followed by Wilke Adolphson of Sweden (400 Husqvarna), Wollsink of Holland (400 Husqvarna), Petr Homola of Czechoslovakia (490 Jawa), Stig Larsson of Sweden (500 BSA), and Miroslav Kleisner of Czechoslovakia (Jawa) in 6th place. I had gotten tangled behind a crash in the first turn, and came around 12th on the first lap. A real battle evolved among the first four riders, and the 10,000 spectators loved it. While the leaders fought it out, I started to work my way toward the front. The crowd started to yell for me, and that really makes you go hard. I came from 12th to 5th in several laps and started to work on the leaders. Homola had taken the lead at this time, and Wollsink, Kley, and Larsson were just behind, then me. On the eighth lap I passed into 4th position in the deep sand, and overtook Deiter Kley on the next lap for 3rd. As I chased Homola and Wollsink down the main straight and over the 60-mph jump, my engine stopped. A small wire had broken on the ignition coil and I was out of the race.

Over the P.A. system, the announcer said, “Russ Darnell has retired with some sort of mechanical trouble, while he was challenging for the lead.” Then he directed his words towards me, as 1 pushed my bike to the pits: “Russ, aren’t you ashamed? Here it is your wife’s birthday, and you didn’t even win this race for her.” The spectators all laughed.

At the end of the 40-minute plus two-lap race, the East German rider Deiter Kley (CZ) had won. Homola was 2nd, Larsson 3rd, Adolphson 4th, and Gerrit Wollsink from Holland was 5th. The Czech team had five of their riders in the top 10 finishers in that first race.

(Continued on page 73)

Continued from page 71

Back in the pits I removed the flywheel and began to make repairs. Fortunately, Wilke Adolphson lent me a complete ignition plate for the second race, so I wouldn’t have to go into town to re-solder the ground wire. While I took care of the ignition problem, Cheri cleaned the bike, checked the tires, and made sure all the spokes were tightened properly. Most of the East Germans had never even seen Americans before, so when they saw Cheri servicing my Husky, they crowded around to watch in amusement. The bike was soon running again, and while I tested it down a side road, Cheri offered the basket of cherries around to the people who came to watch us. This action delighted everyone, and even some of the Stendal police and Soviet soldiers joined in sharing the fruit.

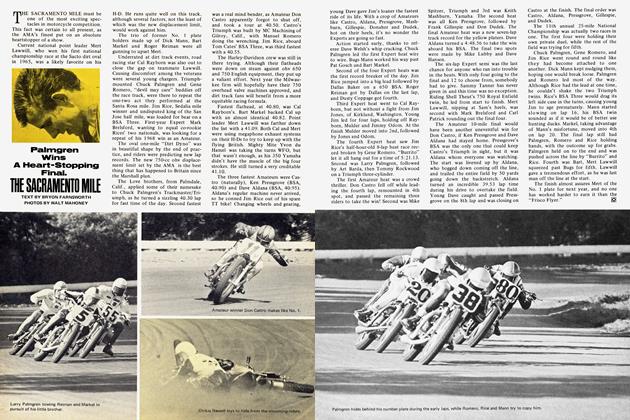

At the start of the second event, I was looking over my shoulder when the starter dropped the flag, so I got a rather poor start. My wife kept the lap charts and said that Kley took the lead straightaway, then came Wollsink, Rasmussen of Denmark (BSA), Vane of Czechoslovakia, Homola, Larsson and Adolphson. I was 18th on the first tour. On Lap 4, I passed Jaatinen from Finland, and moved into 10th spot. From there I came up fairly quickly to 5th, passed Larsson for 4th, and overtook Kley for 3rd. Then the engine stopped again! Two DDR soldiers pushed me for about 200 yards until their wind gave out, then a Swedish mechanic ran to help me, with a spare spark plug.

The ground wire on the new ignition I borrowed had been a trifle too short, and vibration had broken it in the same place as before.

The circuit was very long, and so were the races. I could see that the pace had slowed as riders became tired. Homola took the lead in the late stages of the race, and Kley could not quite match his speed. Larsson on his Cheney -BSA overtook Adolphson and Wollsink, then passed Kley on the next to last lap. At the finish it was Homola, Larsson, Kley, Wollsink and Adolphson, in that order. The lap scorers were quite efficient, and 20 minutes after the event mimeographed copies of the official results were handed out. Petr Homola (Jawa) from Czechoslovakia was 1st; Dieter Kley, DDR, riding CZ, was 2nd; then Stig Larsson from Sweden on a BSA, 3rd; Gerrit Wollsink from Holland on a Husqvarna was 4th; and Wilke Adolphson from Sweden on a 400 Husqvarna finished 5th.

The day of racing over, we made ready to go into Stendal for the awards banquet. Before we left the pits, some Czech and East German riders came over and wanted to trade souvenirs. I traded one of my “Tracy’s of Burbank” T-shirts for a blue Czech team jumper with a gold and red lion emblazoned across the chest. We did a lot of haggling and trading of odds and ends. A crowd stopped to watch, and even one of the DDR policemen tried on one of my Husqvarna T-shirts over his uniform, then put his hat over his heart hamming it up.

An East German couple rode with us back to town, to show us the way to the banquet. They also served as translators on the way out of the pits where we were mobbed by people. It started as a small flow of well-wishers and autograph hunters, then it turned into an avalanche of good will that buried the car so we could not move. Men, women, children, soldiers came from all directions to hand us bits of paper, flags, match boxes, hot dog wrappers (complete with mustard), programs, cigarette boxes. Every conceivable type of article that could be written on was given to us to autograph. I signed my name, and in every case wrote “USA” below my signature. It seemed as though everyone wanted some proof that he or she had come into contact with someone from the “outside world.” In the crush of spectators that surrounded us there also were three Soviet soldiers who congratulated us on the Apollo moon shot.

The banquet was held in a huge hall, decorated with portraits of Lenin; it was the officers club of the DDR army. During the meal, the Bürgermeister of Stendal presented Cheri with another bouquet of roses and a box of candy, gifts from the people of the town. Cheri stood up, toasted the town and all the people, and thanked them for a very enjoyable stay in their country. This met with loud applause and everyone then proceeded to get smashed.

Next morning (Monday) we were taken to a nearby food factory and treated to a huge breakfast. Actually the morning was pretty hungover, so no one ate too much. We were each given a bottle of cognac and a bottle of coffee liqueur as a souvenir of our visit to Stendal. Just looking at the booze was enough to cause minor headaches and stomach disorders, so the bottles quickly disappeared into the trunks of the cars. Breakfast over, we bade farewell to all our East German friends, and set out for Magdeburg again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue