LEGISLATION FORUM

Special Report: The Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

PART IV

J. BRADLEY FLIPPIN

THIS is the fourth article of a series dealing with governmental organizations influential in formulating motorcycle legislation.

NATIONAL COMMISSION ON SAFETY EDUCATION (NCSE)

The National Commission on Safety Education is one of 60 commissions, departments, and institutes of the National Education Association (NEA). The NEA is a professional organization of teachers, comparable to the American Medical Association for doctors. The NCSE is headed by Executive Secretary Dr. Norman Key. Dr. Ray F. Wahl, a member of the commission, was interviewed concerning certain aspects of the MS&ATA’s recent contract with the commission.

“The purpose of the project,” explained Dr. Wahl, “is to accomplish the research and other procedures fundamental to developing a body of knowledge for the implementation and the teaching of motorcycle safety education programs in schools.

“The first phase involved the collection, organization, analysis and evaluation of data. We collected all the published and unpublished literature we could find. Secondly, we developed a survey instrument to determine the status of motorcycle driver education throughout the country. Then we developed another survey instrument, designed to reveal the status of motorcycle education in local school districts.

“The second phase was to select participants to serve on an advance study clinic for the programming of a national conference held early this year in the NEA education center.”

How do the results you obtained compare with the total number of high schools in the nation?

“Of about 30,000 high schools, we initially were able to identify only 50 definite school programs; however, there are some 600 high schools in California (57 in Los Angeles alone), some of which offer some form of motorcycle instruction. California is the heaviest user of motorcycles in the country (3 5 3,000 of the nation’s 2,000,000).

“I think the reason California has such programs is that the educators recognize the problem and have reacted to it. Much of our knowledge and resources stem from California. It seems they have taken a pioneering role.”

Do any of the schools that do teach motorcycle safety include actual practice on a machine?

“The courses vary. They range from a few hours in the classroom phase of driver education to a total program concept, including instruction on the motorcycle. Survey returns indicate the total time of such instruction varies from 3 to 20 hours. There is no standard yet.

“A large percentage of the 30,000 high schools already have automobile driver education programs. Once the effects of the Highway Safety Act of 1966 are fully felt, every school should provide for motorcycle instruction of some sort. Some schools won’t have a motorcycle environmental situation. However, I think that where the need exists, the training will be provided eventually.”

What prevents the inclusion of motorcycles in existing driver education programs?

“I think it’s the lack of knowledge— the lack of a guideline. The average educator hasn’t become aware of this problem. Local motorcycle clubs, police, and other groups can aid in this situation. Their support and their cooperation with schools is an important factor. For example, they can assist schools by providing technical help and opportunities for the pursuit of worthwhile educational activities in connection with motorcycles.”

If a local school system wants to include motorcycle training, who can provide information?

“Following the conference, recommendations will be published to provide the guidelines for the development and implementation of such courses.”

The following is a report on the first National Conference on Motorcycle Safety Education, a three-day meeting sponsored by the NCSE and the American Driver and Traffic Safety Education Association, another department of the NE A, in cooperation with the Motorcycle, Scooter and Allied Trades Association. Though most of the participants were members of state educational agencies, the motorcycle industry, the MS&ATA, the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators, the National Highway Safety Bureau of the Department of Transportation, law enforcement officers, and other concerned organizations were well represented.

Dr. Paul O. Carr and Dr. Norman Key, both of the NCSE, opened the session by posing questions which they hoped the combination of talents present could answer. They expressed their desire that the result of the conference would be a publication setting forth recommended policies and guidelines for educators, and their belief that this first national conference could be the most significant safety education event of the century.

After a panel discussion, which further stimulated the exchange of ideas, the attendees were divided into six working groups which were to detail various aspects of a total motorcycle safety education picture.

Each of the groups consisted of a leadership team (a leader and a recorder, both of whom were generally educators) and two or three resource persons (from industry or government). Group topics were: (1) Planning Instruction—to study suggested instructional methods and procedures; to determine objectives; to devise useful learning activities for students; and to select or prepare materials, equipment, and facilities for instruction; (2) Program Personnel—to determine qualifications of teachers, preparatory experiences needed, general and special supervision, and the role of the “paraprofessional”; (3) Administration of the Program—to provide guidelines for selection of students, meeting instructional costs, insurance provision, scheduling of instruction, and maintenance of vehicles, equipment, and facilities; (4) Teacher Preparation—to study the role of colleges and universities, and the provision of in-service opportunities for experienced teachers and laboratory activities for prospective teachers; (5) Resource and Leadership Support—to investigate the role of the state departments of education and other state agencies, legislation needed, program financing, license and permit requirements, role of federal government agencies and community relations; and (6) Evaluation and Research—to devise means of determining student progress through traditional tests, observation and self-evaluation by the student; to design ways of testing various teaching techniques; and to assess program elements.

On the second day, preliminary group reports were presented to a general assembly of the conference. Controversial topics were open for comments from all. Most intriguing was one group’s suggestion that “paraprofessionals” participate in the motorcycle education program. A paraprofessional is a person skilled in a particular area (such as an expert motorcyclist), who does not possess a teaching certificate. The NEA’s policy on the paraprofessional (auxiliary personnel/teacher aide) states that he should not be allowed to actually instruct, but may perform clerical duties, arrange field trips, transport students and the like.

Thus, in the motorcycle field, it appears that a paraprofessional might be limited to demonstrating his skills, showing what should and should not be done on a motorcycle, under the direction of the regular driver education instructor. He might also be required to show films, prepare a practice course, and perform other non-teaching tasks such as those mentioned above. (He could not transport a student by motorcycle).

Another topic which inspired much discussion concerned whether motorcycle instruction should be part of the regular driver education course or be the subject of a separate course. Those against this special provision believe it is not the school’s purpose to teach students to be expert motorcyclists, rather the school should promote an awareness of motorcycles and provide for those who desire it the necessary tools to insure their safety if they chose to ride a motorcycle.

On the third and last day, final group reports and recommendations were presented to the entire conference. The material will be reviewed and coordinated by an editorial staff for publication. Title, cost and date of availability of the report will be announced in the future. Its recommendations will not be enforced by law, nor will such a program be required by law. However, the report will contain guidelines which state and local school districts may use in implementing a motorcycle safety education program. [g]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

OCTOBER 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

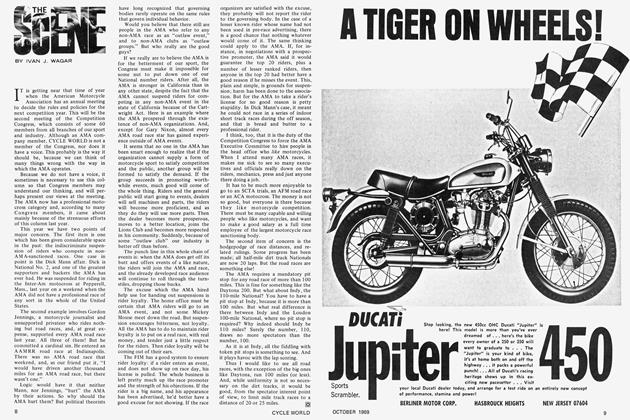

DepartmentsThe Scene

OCTOBER 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

OCTOBER 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

OCTOBER 1969 -

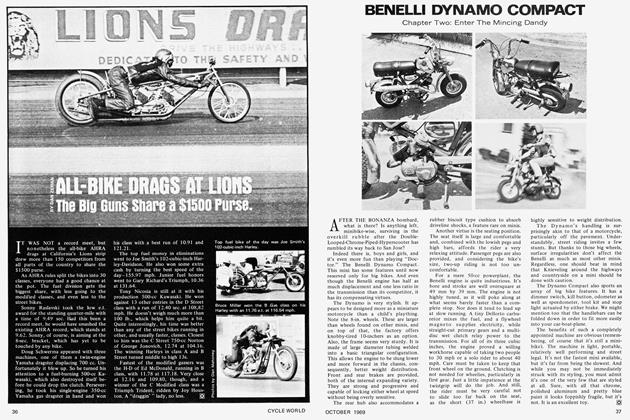

Competition

CompetitionAll-Bike Drags At Lions the Big Guns Share A $1500 Purse.

OCTOBER 1969 By Dan Zeman -

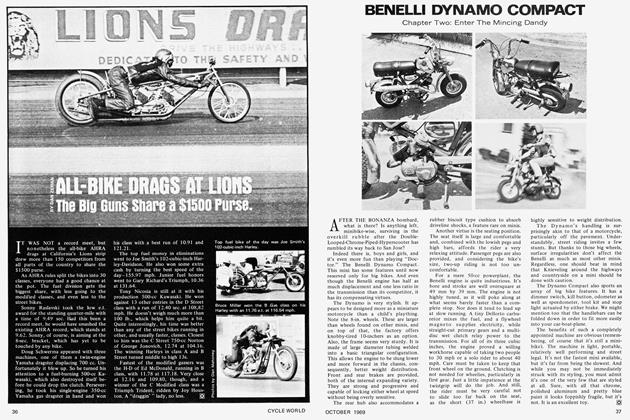

Tests

TestsBenelli Dynamo Compact

OCTOBER 1969