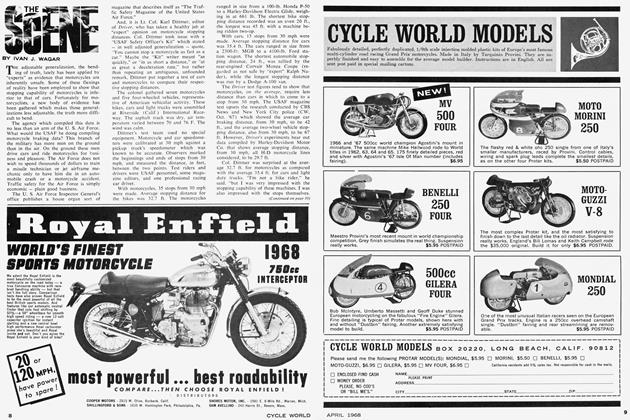

BULTACO 360 BANDIDO

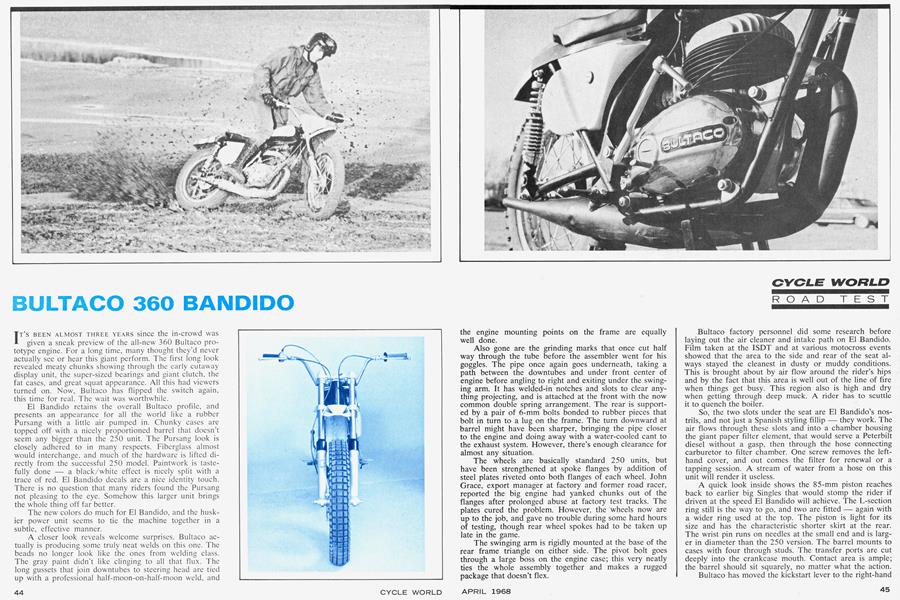

IT'S BEEN ALMOST THREE YEARS since the in-crowd was given a sneak preview of the all-new 360 Bultaco prototype engine. For a long time, many thought they'd never actually see or hear this giant perform. The first long look revealed meaty chunks showing through the early cutaway display unit, the super-sized bearings and giant clutch, the fat cases, and great squat appearance. All this had viewers turned on. Now, Bultaco has flipped the switch again, this time for real. The wait was worthwhile.

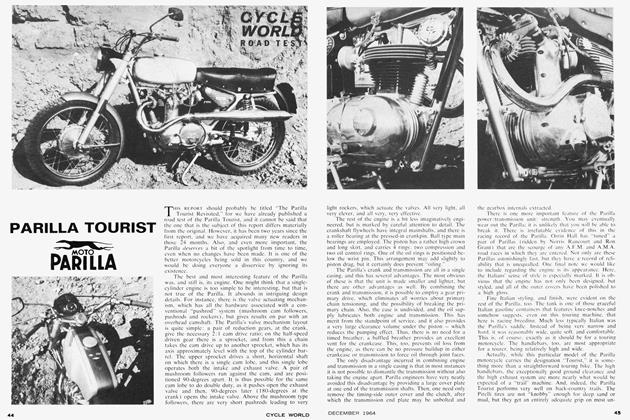

El Bandido retains the overall Bultaco profile, and presents an appearance for all the world like a rubber Pursang with a little air pumped in. Chunky cases are topped off with a nicely proportioned barrel that doesn't seem any bigger than the 250 unit. The Pursang look is closely adhered to in many respects. Fiberglass almost would interchange, and much of the hardware is lifted directly from the successful 250 model. Paintwork is tastefully done — a black/white effect is nicely split with a trace of red. El Bandido decals are a nice identity touch. There is no question that many riders found the Pursang not pleasing to the eye. Somehow this larger unit brings the whole thing off far better.

The new colors do much for El Bandido, and the huskier power unit seems to tie the machine together in a subtle, effective manner.

A closer look reveals welcome surprises. Bultaco actually is producing some truly neat welds on this one. The beads no longer look like the ones from welding class. The gray paint didn't like clinging to all that flux. The long gussets that join downtubes to steering head are tied up with a professional half-moon-on-half-moon weld, and the engine mounting points on the frame are equally well done.

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Also gone are the grinding marks that once cut half way through the tube before the assembler went for his goggles. The pipe once again goes underneath, taking a path between the downtubes and under front center of engine before angling to right and exiting under the swinging arm. It has welded-in notches and slots to clear anything projecting, and is attached at the front with the now common double spring arrangement. The rear is supported by a pair of 6-mm bolts bonded to rubber pieces that bolt in turn to a lug on the frame. The turn downward at barrel might have been sharper, bringing the pipe closer to the engine and doing away with a water-cooled cant to the exhaust system. However, there's enough clearance for almost any situation.

The wheels are basically standard 250 units, but have been strengthened at spoke flanges by addition of steel plates riveted onto both flanges of each wheel. John Grace, export manager at factory and former road racer, reported the big engine had yanked chunks out of the flanges after prolonged abuse at factory test tracks. The plates cured the problem. However, the wheels now are up to the job, and gave no trouble during some hard hours of testing, though rear wheel spokes had to be taken up late in the game.

The swinging arm is rigidly mounted at the base of the rear frame triangle on either side. The pivot bolt goes through a large boss on the engine case; this very neatly ties the whole assembly together and makes a rugged package that doesn't flex.

Bultaco factory personnel did some research before laying out the air cleaner and intake path on El Bandido. Film taken at the ISDT and at various motocross events showed that the area to the side and rear of the seat always stayed the cleanest in dusty or muddy conditions. This is brought about by air flow around the rider's hips and by the fact that this area is well out of the line of fire when things get busy. This region also is high and dry when getting through deep muck. A rider has to scuttle it to quench the boiler.

So, the two slots under the seat are El Bandido's nostrils, and not just a Spanish styling fillip — they work. The air flows through these slots and into a chamber housing the giant paper filter element, that would serve a Peterbilt diesel without a gasp, then through the hose connecting carburetor to filter chamber. One screw removes the lefthand cover, and out comes the filter for renewal or a tapping session. A stream of water from a hose on this unit will render it useless.

A quick look inside shows the 85-mm piston reaches back to earlier big Singles that would stomp the rider if driven at the speed El Bandido will achieve. The L-section ring still is the way to go, and two are fitted — again with a wider ring used at the top. The piston is light for its size and has the characteristic shorter skirt at the rear. The wrist pin runs on needles at the small end and is larger in diameter than the 250 version. The barrel mounts to cases with four through studs. The transfer ports are cut deeply into the crankcase mouth. Contact area is ample; the barrel should sit squarely, no matter what the action.

Bultaco has moved the kickstart lever to the right-hand side of the machine, and it must be removed to drop the primary cover. The kick lever is quite long, not especially easy to operate. However, the machine never failed to kick start, and, aside from a slight tendency to slip when kicked for the camera, it gave no trouble. It did not get in the way when clambering about the machine with a foot seeking a peg.

The clutch now is operated by an arm on top of the rear engine case. Gone is the frayed cable that ran under the engine to jam every time a rider tried a rock pile.

Primary drive is by helical gearing. There is a cush drive on the engine that eases shock loadings on clutchless changes. Some sort of cushion is required on these giants as inertia enters into things when dealing with Gold Starsized pistons.

Rear drive chain, at last, is up to the work. El Bandido is fitted with much heavier chain, adjustment of which wasn't changed during testing and still was in proper range at completion.

The fork has slightly stronger springs than those used in the Pursang. Damping has been modified slightly to cope with El Bandido's extra poundage. The front suspension worked very well and felt like later Bultaco forks generally do, secure and precise. Chromed Betör spring/ shock absorber units are used at the rear, and do an excellent job of keeping the wheel up tight. Owners once swapped these Spanish units as soon as they took possession of the machines, but things have changed. The Betor product now is a very sophisticated piece of motocross hardware.

El Bandido talks back and stings if it isn't kicked with determination, but it invariably fired up quickly, once the knack was acquired. The starter folding crank tends to hang up on the muffler, and sometimes requires return by hand. The exhaust note is fierce — not much different than that of smaller models. The engine begins two-cycle operation nicely with just a slight load.

The Femsatronic pointless ignition system works faithfully, delivering a big, fat fire all the while. The plug lead came adrift after many rips through the quarter mile, after riders hadn't heard a miss all day. The engine was taken past 9000 rpm on the test bed, but nothing flew off, so the loose wire probably was no major malfunction.

Perhaps the biggest single thing, the strongest single impression, is the smoothness of the engine and drive train. El Bandido feels exceptionally smooth no matter what rpm range it is working in. Over-revving produces none of those heavy tremors that are often experienced on various big two-stroke machines. The very short stroke must contribute to this willingness to rev freely, and to this engine's smoothness which is superior to some two-cycle roadster machines.

But there's more to it than that. The factory claims the design was for a 360 that is quicker on any motocross course than the smaller Bultacos — which hasn't been the case with some machines of other marque. Bultaco's plan to build a 360 that behaved like a 360 seems to have worked out. An exceptionally savage 250 will be necessary to hold El Bandido at bay. Shift quality was a trifle lazy at the start of the test, but got progressively better as hours on the engine accrued. The throw is not overly long. Shifts fell like the handle of a knife passing through slightly chilled butter. By the end of the day, it could be flicked in and out of gear as fast as the rider could work the pedal. Shift mechanism could not be faulted.

The Pursang tends to be difficult on a missed gear, often not engaging until the clutch is pulled, and all the right things are done — especially from fourth to fifth. El Bandido seems to have avoided this. If a gear is missed, a cure can be effected by rolling off throttle as a bit of pressure is held on the pedal. It always will go home — and stay there.

At any place from just over idle, there's a bottomless supply of torque. The machine yanks the wheel up unless the rider positions himself properly and feathers a bit at the proper instant. Oddly enough, the front wheel lifted many times during the test, but seemed to rise only a few inches, then hold as El Bandido charged away. Looping isn't El Bandido's big problem, but the rider needn't bounce the front fork to initiate a wheelie.

The carburetor wasn't just right at the extreme low end, as the engine would sometimes quit when hard braking was required. The float level probably was a trifle high; perhaps more experimenting with low speed mixture is indicated. Once off idle, all went well — carburetion was clean all the way up. The slide showed no signs of sticking and action at the throttle twistgrip was exceptionally light. However, the Amal concentric is just another example of the double standard which has long applied when comparing certain British components with their equivalents from other countries.

It isn't clear why Bultaco fitted this particular carburetor to El Bandido, but one of the firm's licensed monobloc versions, which always does a fine job and is very easy to service, probably would have been more desirable. The concentric unit is covered with tiny screws that are inordinately difficult to remove with the carburetor in place. Even the top piece that holds the slide and spring in position is attached with a pair of screws. It seems much easier to change main jets by removing the entire carburetor as the heads of the wretched mini-screws aim down at the engine. This occurs on a machine that could require three or four changes in a day. Why doesn't Bultaco use a spring clip to hold the float bowl in place? This system is good enough for Volkswagen or Corvair rocker box covers, and is used with no problems on some Japanese carburetors.

Once under way, the bigger engine of El Bandido does not feel significantly heavier or larger. Except for markedly advanced power characteristics, it feels much like a 250 Pursang, but is a trifle slower in its response to some situations.

A Pursang probably could give El Bandido a bad time on a really tight track with many sharp bends, but given a chance to unwind and call on that awesome torque, El Bandido should keep little brother back in a hail of flying gravel. There is a bit of cam action early in the rpm band. It is not fierce, however, and comes in at a sane pace. From there to infinity it goes quite straight, with no second stage burst to put a rider off on grassy sweeper.

The controls are nicely done. Bultaco has retained the clamp-on bars borrowed from speedway practice. Both brakes worked well; the rear seemed to be more powerful than the apparently identical unit on the 250s. Perhaps there has been a change in lining. The bar rubbers still are the tot's tricycle components that leave half the rider's hand with no support, and the same surface pattern that tears up fine "Just Like Joel" gloves. A change for the better could be made here.

The front brake has a gradual action that gives very secure response when braking on poor footing. This setup permits a really fierce hang-up — or a one finger stall at lazy pace. On drag strip braking tests, everything was locked up as soon as El Bandido cleared the clocks. The front brake brought the forks to full compressions, and set the knobs growling without straining the hands. There was no high-spot effect. El Bandido just came to an abrupt, smooth stop, time after time.

The 19-in. front wheel will satisfy the majority of U. S. riders, but some of the areas that feature truly rough motocross layouts may require a 21-in. wheel and tire. The smaller section of the 21-in. tire offers greater steering precision in difficult going, but anything that gets a trifle packed would require the 19-in. component. The test machine was fitted with Pirelli knobs front and rear, not an ideal tire in mud, but an excellent compromise tire for tracks with varying terrain.

El Bandido was ridden hard for a couple of hours in very muddy going, and didn't ever get truly hot. The cylinder could still be touched briefly, even though mud found its way between some of the fins. The engine showed no stickiness, and never approached 0.000-in. clearance and the dreaded squawk, in spite of screaming it at top rpm for almost half the quarter-mile runs. It seemed to be about wound out at that point and just roared off the last half without protest.

An access road provided a series of nice high speed bends of reasonably good surface, just the thing on which to try a few slides to form an impression on tail hang-out. Entering at about 60 mph, El Bandido could be cranked out at the rear almost as much as the rider wished. It held a smooth line with feet up and came out of the slide with a modest snap as everything lined up. El Bandido's behavior in. this situation was outstanding, even on some return run slides to the right. In rougher going, the front wheel can be lofted over anything in the way by merely getting on the throttle a bit. It doesn't do the short, violent shunts up front that the Pursang can surprise a rider with, but rises in simple, lazy boosts that never end in a loop.

The factory claims that swing arm pivot location has much bearing on this factor. Bultaco engineers have researched a variety of configurations before settling on the obviously satisfactory location. The factory will find it difficult to improve on this suspension for the work intended. El Bandido would roll into some full circle second gear slides with the rider's feet in place. This was done on a muddy surface, with good base underneath. Once the machine convinced the rider that it wouldn't let go at the front when the feet were where they belonged, both wheels could be kept sliding and the arc maintained by weight shifting and throttle nudges. Many machines won't permit such liberties. Getting away with it on El Bandido means that things are right.

Juan Soler Bulto, factory development chief, and John Grace answered many questions on El Bandido, and their frank manner concerning early problems with prototypes was most helpful. They revealed the existence of a 350-cc road race engine, already producing 51 bhp, and possibility of a slightly detuned version — 47 or 48 bhp— becoming available for TT racing, or superfast scrambles tracks. This won't happen tomorrow, so El Bandido is the best immediate bet. There is nothing in the class that will touch it on raw horsepower.

The Amal concentric carburetor is made in Spain under license, and has benefited from much experimenting at the Bultaco factory. It has certain modifications from standard, and throttle response has been considerably improved since first testing was carried out. Bultaco people still aren't entirely satisfied with its behavior, and will continue to experiment on the controversial marvel. It does deliver enough fuel/air mixture to make El Bandido perform. Power seems wide and clean all the time. The large boss at the upper rear of the engine is bolstered with a steel sleeve, as mentioned earlier. This boss is used as additional support for the swinging arm, and the pivot bolt passes through this sleeve before tying to either side of the frame. The sleeve actually is two pieces, with the break line matching the joint of the crankcase halves, which creates no problems when sliding the cases apart, and which insirres that any possible motion will not destroy the close tolerance between bolt and engine.

The crankshaft is fitted with two single row ball bearings on the drive side, while the magneto side uses a large roller bearing with cage. These stay in position ort dismantling. There is none of that old business of packing with grease and wondering what happened as the case slid on, and was that the dull thud of a roller gone wild? The crankpin diameter has been increased to 20 mm, up 2 mm from earlier units. No problems have been experienced on prototypes. The piston pin is out to 18 mm, again 2 mm larger than the 250 unit. It runs in needle bearings. The factory has not experienced a problem with seizures in spite of the monster bore.

Pistons are made by a branch of Bultaco and are built under license from Mahle in Germany. There is a very close working relationship between factories. Bultaco, with technical effort aimed at perfecting the pistons for its particular needs, has pioneered certain features that put its product in the same superior league as the parent product.

Bulto and Grace said a number of frame designs had been tried for the 360 engine, and lengthy experimentation with swing arm layouts had been carried out before the production version was frozen. A machine was desired that looked like a Bultaco, that would retain the Bultaco reputation for high output without great expense for coffee can appearance, common to some very good 360 equipment, and finally, that would be at home on the worst of European motocross courses. Time will tell how close Bultaco has come to the latter quest, but there can be no question that sheer good looks and brilliant horsepower are offered by El Bandido.

This new giant from Spain is an impressive piece of racing gear. It is difficult not to be awed every time it is fired up.

BULTACO

360 EL BANDIDO

SPECIFICATIONS

$1179