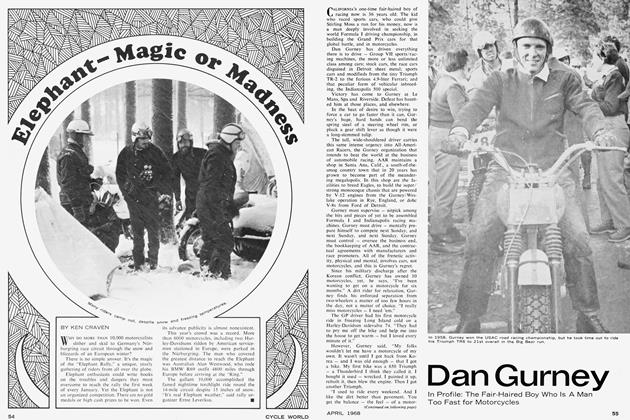

HARLEY-DAVIDSON TAKES AIM

All-American Men and Machines Seek the All-American No. 1

Drive for Daytona:

To see all-out racing machinery under talented hands, to observe ideas become speed increases, is a privilege. Such an honor was accorded editors of CYCLE WORLD by Harley-Davidson Motor Co. These editors were onlookers at every step of preparation of Harley-Davidson motorcycles for the 200-mile AMA Daytona Classic for 1968. Herewith is the story of these motorcycles, from foundry to high-banked asphalt. — Ed.

No. 2 STATUS may be okay for Avis, but with Harley-Davidson, that number plate may as well be No. 2000. No. 2 is a long way from No. 1, which is what Harley-Davidson was in American championship motorcycle racing. H-D is devoted to the exchange of No. 2 for No. 1 — and was for is.

What rankles with such intensity is that No. 1 on U. S. soil is a British motorcycle. Flag waving, Revolutionary War jokes and patriotism aside, it's a matter of intense corporation pride that the nation's only motorcycle manufacturer seeks to regain its championship within the confines of the United States.

In 1967, Triumph, for openers, beat H-D rather handily in the 200-mile expert event at Daytona — and with record speed. That set the tone for the entire Gary Nixon/ Triumph season — and generated gallons of excess stomach acid in Milwaukee.

This year, if Harley-Davidson doesn't win at Daytona, and subsequently finish the season as AMA points leader, it won't be because the company has shied away from a bust-gut try.

Chief of this effort to regain No. 1 plate, and thereby sooth the corporate stomach, boost H-D sales, and keep American motorcycling American, is Dick O'Brien. His direct gray eyes, behind thick lenses, seem able to X-ray motorcycle engines. His flat gray crewcut is the same color as the cast iron of his sidevalve VTwins on which he practices his wizardry. His official title with the organization is '"Racing Engineer."

O'Brien started the assault on Daytona 1968 immediately following the 1967 loss. It was obvious, in the case of the Triumph victory in Florida, that horsepower and small size were keys to the win. O'Brien knew where he could obtain horsepower; the need was for a smaller motorcycle.

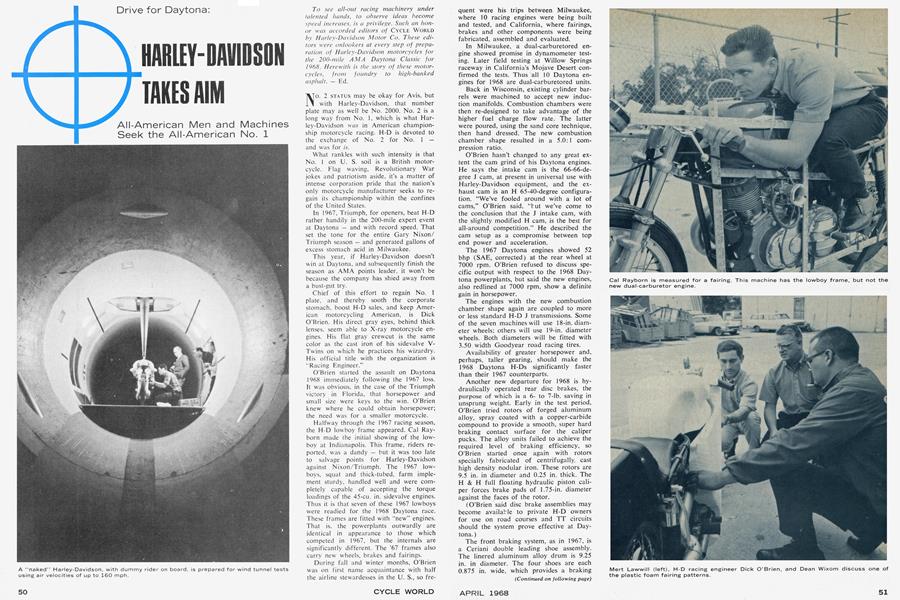

Halfway through the 1967 racing season, the H-D lowboy frame appeared. Cal Rayborn made the initial showing of the lowboy at Indianapolis. This frame, riders reported. was a dandy — but it was too late to salvage points for Harley-Davidson against Nixon/Triumph. The 1967 lowboys, squat and thick-tubed, farm implement sturdy, handled well and were completely capable of accepting the torque loadings of the 45-cu. in. sidevalve engines. Thus it is that seven of these 1967 lowboys were readied for the 1968 Daytona race. These frames are fitted with "new" engines. That is, the powerplants outwardly are identical in appearance to those which competed in 1967, but the internals are significantly different. The '67 frames also carry new wheels, brakes and fairings.

During fall and winter months, O'Brien was on first name acquaintance with half the airline stewardesses in the U. S., so frequent were his trips between Milwaukee, where 10 racing engines were being built and tested, and California, where fairings, brakes and other components were being fabricated, assembled and evaluated.

In Milwaukee, a dual-carburetored engine showed promise in dynamometer testing. Later field testing at Willow Springs raceway in California's Mojave Desert confirmed the tests. Thus all 10 Daytona engines for 1968 are dual-carburetored units.

Back in Wisconsin, existing cylinder barrels were machined to accept new induction manifolds. Combustion chambers were then re-designed to take advantage of the higher fuel charge flow rate. The latter were poured, using the sand core technique, then hand dressed. The new combustion chamber shape resulted in a 5.0:1 compression ratio.

O'Brien hasn't changed to any great extent the cam grind of his Daytona engines. He says the intake cam is the 66-66-degree J cam, at present in universal use with Harley-Davidson equipment, and the exhaust cam is an H 65-40-degree configuration. "We've fooled around with a lot of cams," O'Brien said, "but we've come to the conclusion that the J intake cam, with the slightly modified H cam, is the best for all-around competition." He described the cam setup as a compromise between top end power and acceleration.

The 1967 Daytona engines showed 52 bhp (SAE, corrected) at the rear wheel at 7000 rpm. O'Brien refused to discuss specific output with respect to the 1968 Daytona powerplants, but said the new engines, also redlined at 7000 rpm, show a definite gain in horsepower.

The engines with the new combustion chamber shape again are coupled to more or less standard H-D J transmissions. Some of the seven machines will use 18-in. diameter wheels; others will use 19-in. diameter wheels. Both diameters will be fitted with 3.50 width Goodyear road racing tires.

Availability of greater horsepower and, perhaps, taller gearing, should make the 1968 Daytona H-Ds significantly faster than their 1967 counterparts.

Another new departure for 1968 is hydraulically operated rear disc brakes, the purpose of which is a 6to 7-lb. saving in unsprung weight. Early in the test period, O'Brien tried rotors of forged aluminum alloy, spray coated with a copper-carbide compound to provide a smooth, super hard braking contact surface for the caliper pucks. The alloy units failed to achieve the required level of braking efficiency, so O'Brien started once again with rotors specially fabricated of centrifugally. cast high density nodular iron. These rotors are 9.5 in. in diameter and 0.25 in. thick. The H & H full floating hydraulic piston caliper forces brake pads of 1.75-in. diameter against the faces of the rotor.

(O'Brien said disc brake assemblies may become available to private H-D owners for use on road courses and TT circuits should the system prove effective at Daytona.)

The front braking system, as in 1967, is a Ceriani double leading shoe assembly. The linered aluminum alloy drum is 9.25 in. in diameter. The four shoes are each 0.875 in. wide, which provides a braking surface total width of 1.75 in. Lining is a U.S.-made Raybestos compound of moderate hardness.

(Continued on following page)

It's a Gas

It's a gas — a very fast gas. Harley-Davidson intends its fuel delivery system for the 1968 Daytona Classic to be equally as fast, hopefully, as will be its road racing machinery. Former racer Jerry Branch, now super/tuner for Harley-Davidson of Long Beach, Calif., built 10 of the quick-dump fuel cans for the H-D racing team. Essentially 5-gal. sealer type steel cans, the quickdumpers feature top air seals made of children's rubber balls, and bottom liquid seals made of household variety toilet flush tank balls. The seals are mounted on either end of a vertical shaft, spring loaded and notched for a pushbutton triggering mechanism. At the bottom funnel/orifice, a venturi device admits air to speed fuel flow. A plastic gasket prevents fuel leakage, and two overflows, fitted with plastic hose, carry excess fuel well away from speed-hot engines. Fast? The quick dumpers will deposit a full 6 gal. of gasoline into a tank in only 5 sec.

The front forks of the seven racing machines also are of Ceriani manufacture, borrowed from the H-D Sprint series, but have been modified to the extent that they carry stiffer than original springs — made in Milwaukee — and SAE 40 oil. The swinging arm rear suspension is supported by coil springs and Girling road racing shock absorbers 1 1.875 in. in length.

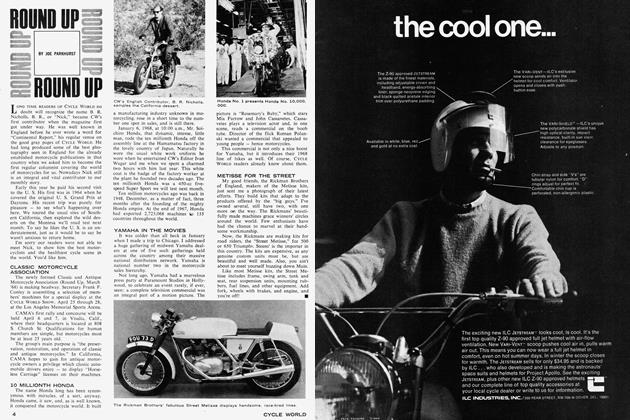

In creating the H-D racing stable for '68, O'Brien lavished as much attention and talent on aerodynamics as he did on the new combustion chamber design and dual carburetion. He commissioned Wixom Bros, of Long Beach, Calif., makers of the popular Ranger fairings, to design, build and test fairings and fuel tanks for H-D road racing machinery.

The brothers Wixom, Dean and Stan, designed a group of experimental fairings to enclose the '68 bikes. Among the designs built were one of super narrow configuration, aimed at major reduction in overall frontal area; and one somewhat less narrow, with fuller side coverage and a longer, less flattened forward projection.

In the Wixom shop, patterns were made from light plastic foam, then female molds were built over the patterns. The fiberglass fairings and tanks were laid into these molds. Once the prototype fairings were completed, they were thoroughly tested.

The prototype fairings, and a fat, dustbin-like KR fairing from Daytona 1967, were taken to the 10-ft. diameter wind tunnel at the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

There, with the aid of William H. Bettes, director of the lab's low speed aerodynamic test facilities, and technicians, the Wixoms and O'Brien put the fairings through their paces.

The air stream of the tunnel is projected by a $70,000 aluminum propeller powered by a World War I submarine electric drive motor. Air temperature in the tunnel is held constant by water cooling and introduction of cool outside air as frictionheated inside air is bled off.

The initial tests were made with a bare bike, aboard which was Sierra Sam, a 165lb. test dummy, lent by Sierra Engineering Co., of Sierra Madre. Calif. Purpose of the bare bike runs was to calibrate the sensing equipment for later tunnel trials with various fairings, and to check for flutters and oscillations.

The fairings were tested one by one at air stream velocities up to 160 mph. As Dean Wixom put it, "That old KR fairing proved pretty slippery," with 30 percent less drag than the bare motorcycle. The super narrow fairing was bolted onto the frame, and the wind was forced through the tunnel at racing speeds. The Wixoms' faces grew long indeed, as the narrow unit quite unexpectedly displayed slightly more drag than the KR fairing. Tufts of string, taped onto the fairing in orderly rows, showed turbulence just above ground level, and to the rear of the exposed hand grips and levers, and an extreme pressure buildup just ahead of the crouching Sierra Sam's chest. A transverse dowel spacer was fitted to the narrow fairing to widen it by 2 in. in an effort to direct airflow smoothly past Sierra Sam's plastic and steel legs. Resultant drag was higher still.

The Wixoms and Cal Tech workers fitted a wider, fuller fairing to the machine and air stream testing was resumed. This fairing, Dean Wixom said, was designed "to reach out to assume early command of the air." As wind tunnel air speed approached 150 mph with this fairing, it became obvious that less turbulence prevailed around the rider, and that the wider fairing induced smoother air passage along the ground plane. "This fairing proved pretty good," Dean Wixom explained. "It had significantly less drag than the super narrow fairing. We taped tufts to it, then found that although it offered less drag, it still had some problem areas."

(Continued on page 76)

He continued, "We were so impressed by the slipperiness of the earlier KR fairing that we spent an evening at the shop, making modifications to it. We shortened overall height, and changed some contours with the aid of tape and clay."

The modified KR was taken to the Guggenheim lab wind tunnel where it proved to be the slipperiest of all the fairings tested, including one, not a KR, that previously had been used on a Daytona racer.

During field tests of the prototype modified KR, conducted at Willow Springs, the Wixoms and O'Brien determined that additional ground and wheel lock clearances were mandatory. These changes were incorporated, the design cleaned up, and the modified KR fairing was put into production for Daytona '68. Ten copies were made — three spares to match the three reserve engines.

The production fairings retain many of the curves of the KR predecessor, but are much smaller in overall size. Moreover, the production units are expressly for the lowboy frame configuration.

The 10 fairings were given a three-tone gel-coat paint job, a super difficult task, in the colors of the Harley-Davidson escutcheon, orange and black, with a white accent stripe. There will be no doubt at Daytona as to whose manufacture they are.

The fiberglass fuel tank went through two design stages before it was judged acceptable for competition in the 200-miler. The basic shape was developed by LeGrande Fletcher, talented industrial designer who works closely with the Wixoms. An incredible amount of preparation time was consumed as each of seven tanks was tailored to fit each of the seven H-D factory team riders.

Primary aim of Fletcher's tank design is to keep the rider tucked below the fairing, with his arms and elbows inboard as far as possible, while retaining adequate gasoline capacity for the 200-mile high speed dash.

The seats of the seven machines are not upholstered in the ordinary sense, but are covered with a thin, light pad of Ensolite, a soft, resilient, vibration-absorbent plastic.

These are the seven Harley-Davidson Daytona machines for 1968. At this writing, the riders who make up the H-D team are Freddy Nix, Cal Rayborn, Roger Reiman, Mert Lawwill, Bart Markel, Dan Haaby and Walt Fulton.

Those familiar with American motorcycle racing will recognize these men as Americans all — no Europeans among 'em.

Thus it is that the American motorcycle manufacturer is mounting an effort to regain supremacy of American machinery, ridden by Americans, in America. Perhaps that orange, black and white ought to be red, white and blue.