RACING REVIEW

GOLD CUP 5-HOUR MARATHON

GREGORY STOTT

Apart from the obvious advantages production racing presents its competitors, there often are underlying commercial benefits. Now, unless there is an outstanding result, an average weekend production race—at California’s Carlsbad, England’s Brands Hatch or Ontario’s Harewood Acres—has little commercial value. Results totaled over a sensible number of races, or a major success such as an endurance event, give distributors their advertising bit. Then, despite his effort, the winning distributor probably will claim not to have sold one more machine because of advertising ballyhoo. What is doubly amusing is this contradictory character often is the responsible factor behind a team entry or sponsored ride for some hopeful the succeeding season. Perhaps he really doesn’t believe in advertising hoopla; perhaps the fun of pit indulgence is sufficient. Regardless, distributors and advertising are the way the Gold Cup Marathon tale unfolds.

In eastern Canada, production racing as a regular class received its initiation in April, 1967. The advertising battle linked to it, however, did not gain its fury until more than a year later, when Triumph embarked on a fierce advertising campaign after winning a preparatory 1-hour “minithon.” The Triumph people likely were a little bugged because of Honda’s valid claim to the Canadian l-,6-,12-, and 24-hour endurance records. It was true. Honda had done it, but done it on a track Honda had hired and where only Honda machines ran.

It wasn’t long before other production race minded distributors joined the local newspaper warfare and, depending where observers were standing, most claims had basic truth to them. The question at local bike shops was not, “Who won the race?” but “Did you see last night’s ads?” By the time the marathon rolled around this year, a good deal of interest had been stirred in the “in” groups. The advertising battle had indeed helped the event, because the majority of distributors entered teams.

The track for the marathon was Ontario’s established 1.91-mile Harewood Acre circuit, a flat, safe, albeit slightly dull, course where an 80 mph average is quite good.

Rules require machines to be virtually stock, except for minor safety modifications. Also, riders are not allowed to extend any riding period over 2.5 hours, or to change riders at every fuel stop. The latter is a determining factor in the marathon.

A Le Mans start set all but one of the 46 machines—of which almost all popular makes 250 cc and over were represented—dashing into the esses. Triumph pulled the opening lead, but in the first hour, numerous pit stops made 1st place a transient thing.

Within the second hour, predictions were narrowing to about a half-dozen machines. There were two distributor Triumphs, one ridden by veterans Roger Beaumont and Ken King, the other by Fraser McAninch and Harv Manning. Because the riders of the former machine both have European experience, and because Beaumont has been the most consistent production class winner, their machine was an odds-on favorite.

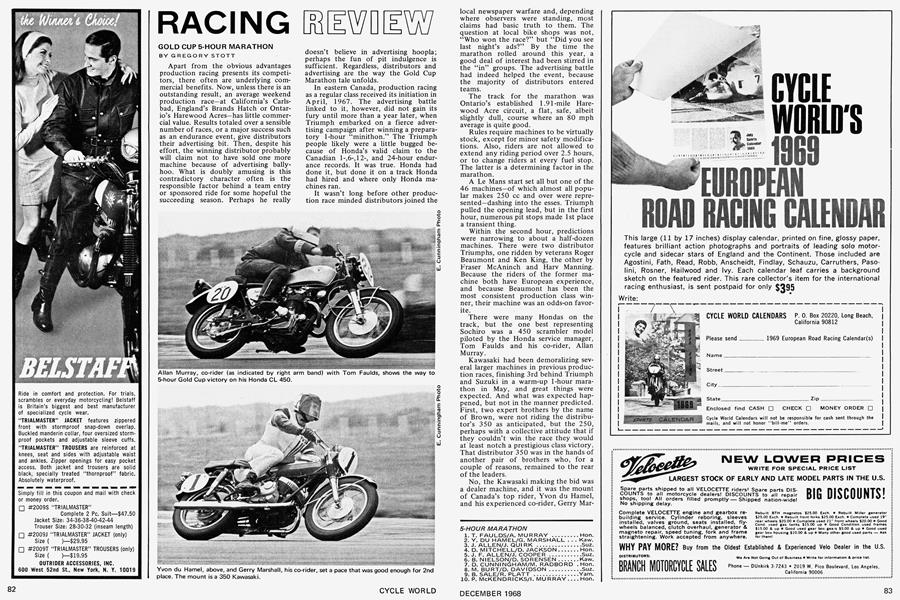

There were many Hondas on the track, but the one best representing Sochiro was a 450 scrambler model piloted by the Honda service manager, Tom Faulds and his co-rider, Allan Murray.

Kawasaki had been demoralizing several larger machines in previous production races, finishing 3rd behind Triumph and Suzuki in a warm-up 1-hour marathon in May, and great things were expected. And what was expected happened, but not in the manner predicted. First, two expert brothers by the name of Brown, were not riding the distributor’s 350 as anticipated, but the 250, perhaps with a collective attitude that if they couldn’t win the race they would at least notch a prestigious class victory. That distributor 350 was in the hands of another pair of brothers who, for a couple of reasons, remained to the rear of the leaders.

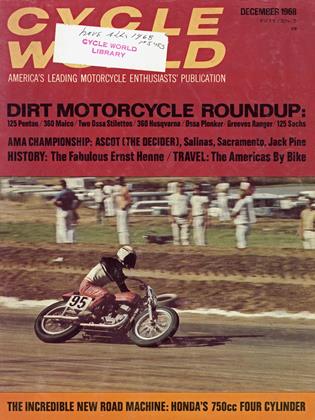

No, the Kawasaki making the bid was a dealer machine, and it was the mount of Canada’s top rider, Yvon du Hamel, and his experienced co-rider, Gerry Marshall. This team had come to the track with both a BSA 650 Firebird scrambler and a Kawasaki 350. The Beezer, though, showed electrical ailments and this, plus the frightening fact that Marshall on the 350 had passed du Hamel riding the 650 in the back straight during practice, influenced them to the Kawasaki.

Another machine that indicated the day might be rewarding was the distributor Suzuki 500/5 under the direciion of two aggressive, if not slightly mad fellows, Jim Allen and Jim Quirk.

Going into the third hour, everyone had pitted, and retirements through crashes or mechanical problems were becoming frequent. Still, almost 40 machines ran, a few only because one rider (the partner of an injured rider) remained with a good machine, and just because it’s admirable to finish. Safety was considered here, though, for if one rider wished to continue and his co-rider was out for some reason, he was required to wait half an hour at pit stops.

Most of the front runners had visited fuel alley three times, some twice, but one, the Faulds/Murray Honda had come in only once. The strategy of pit stops already was evident for their Honda led only one lap ahead of the 2nd place machine, the Kawasaki 350, which already had pitted three times. A pattern was unfolding.

Marshall was demonstrating a good deal of experience on the Kawasaki, but to do justice, it was du Hamel that kept it where it was. And how well he did it! He already was the only rider, the timers had recorded, to complete a lap at more than 80 mph. Despite one less pit stop, the Suzuki 500 was in 3rd place.

The Triumphs were being well ridden but little problems kept the mechanics busy. The McAninch/Manning 650 held 4th, while the other Coventry bomb barely held 6th from the first 250, a Suzuki X-6 ridden very ably by John Allen and John Cooper. Between the Triumphs lay another Honda 450, the effort of Derek Mitchell and Dave Jackson, a rider making a comeback of sorts.

Because a good deal of production race interest centers on the Britain vs. Japan controversy, hour four (three down, two to go) delivered a bit of shock. First, the Beaumont/King Triumph, which had started to gain a bit of lost ground, snapped a primary chain at an estimated 85 mph and, for all the world to see, sent its helpless rider, Ken King bouncing off a front straight haybale. Half an hour later, the brother Triumph followed suit, snapping a rear chain and locking the drive sprocket, but fortunately without such spectacular result. The Triumph camp was not a happy one.

So, the British faith was dealt a blow and it appeared as though little could be done to prevent Oriental domination. Two Norton Commandos were still in contention, but a distance behind the first six. One had lost almost 30 min. when an ignition coil quit, and the problem had to be traced. The other’s chances dwindled when a broken rocker feed pipe and loose contacts demanded pit attention. Both, however, showed their phenomenal strength and handling ability par excellence though. In fact, New Yorker Gene Conway, once an employee of the Norton concern, even ground the right muffler to the exposed inners.

With retirement of the major Triumphs, an entertaining final hour battle developed. The 450 Honda maintained its lead, having made the last of its three pit stops in the fourth hour.

Early in this last hour, cool du Hamel came to the sudden realization, or so it appeared, that 1st place was not so very far away, two laps in fact. He waved Marshall in, and after their sixth pit stop, set off for Murray, who was completing the Honda stint. Tension built. The French Canadian negotiated corners prodigiously and practically crawled under the paint on the straights. With less than 20 min. remaining, he added another lap on the 3rd place Allen/Quirk Suzuki, now five laps behind.

(Continued on next page)

Then, with 10 min. remaining, the Kawasaki passed the Honda in the Esses, but the win was not yet Yvon’s, for he had merely unlapped the Kawasaki and joined the leaders’ lap. Only mechanical failure or a trip to the boondocks in the next few minutes could rob Honda of its victory.

For three-quarters of a lap the latter was a possibility, as a stunned Murray set off for du Hamel, trying to regain what he thought was a lost lead. Frantic “Cool It!” signals set him straight, though, and a few minutes later the race ended. A Honda had completed 202 laps, and had won three-quarters of a lap ahead of the Kawasaki and five laps ahead of the Allen/Quirk Suzuki. The 4th place Mitchell/Jackson Honda 450 was trailing, seven laps behind.

Suzuki stamina gained an X-6 a remarkable 5th place and first 250 position. The riders, John Cooper and John Allen (brother of 3rd place team rider, Jim Allen) dealt their efforts smoothly and consistently. Their finish only 13 laps behind the leader was impressive.

Post race happenings were almost as full of incident as the pre-race action. Partly by reason of the fierceness of pre-race advertising, previous races had been blemished by protests and counter protests. One official of the sponsoring Nortown Motorcycle Club foresaw such clamoring again, and arranged for a competition protest committee to handle contingencies of that nature. The forseen protests came, of course, and the committee played judiciary to some very excited and occasionally unsportsmanlike individuals. Triumph first protested the winning Honda on grounds the tank emblems were removed and that Renolds chain was used. This was defeated because the emblem removal had been passed through scrutineering (on several machines), and as far as the chain was concerned, it was just one of those changeable items. Curiously, Triumph had used racing chain.

Honda counter-protested the Triumph on the basis the Coventry machinery was equipped with close ratio gearboxes, folding footrests and a host of other non-North American features. This protest was dropped, as was one against Suzuki, when Honda learned its protest had been ruled out.

The following week, when Triumph was protested again, the distributor showed a British catalog that lists availability of such a machine to the public on special order. The Canadian Motorcycle Association rule states, “cataloged by the manufacturers and sold to the general public for street use,” but does not specify in North America or in what quantity they should be available.

Then it was Suzuki’s turn to protest the two Kawasakis, the 2nd place machine and the distributor 350, on the grounds the machine had been fitted with different rotary valves, a different carburetor and exhaust system. The first two accusations were dismissed, as was the latter on the distributor 350. The du Hamel/Marshall accusation held some truth, though. The baffle was pulled and to the seemingly honest surprise of both riders, 5 in. had been sawed off. Sensitive tempers were ignited, and after the blue air was cleared, the committee ruled it had been passed through scrutineering and practiced without protest. Additionally, the committee stated the belief that modification had added nothing to the power. It was the Isle of Man once again.

Whether the decision was correct is perhaps debatable. Someone, most likely the sponsoring dealer had shortened the baffle. It was an unnecessary aggravation for any power increase certainly was infinitesimal. The two riders were very capable and their 2nd place was won by such capability, not devious unsportsmanlike means.

Elsewhere in the pits, the more pleasant side of the game was reflected. The finishing winner, Allan Murray, gave deserved credit to co-rider Tom Faulds. A few yards from him, two BSA enthusiasts announced to anyone who would listen that their 1967 Thunderbolt had the most miles of any motorcycle in the marathon—21,500. “Wow!” said the

passersby as they nonchalantly glanced at the speedometer on the worn Beezer. Their machine, though well down and suffering from a mid-race clutch change, was one of more than 30 machines that finished.

Yvon opined to a few fans that because of lower speeds, rest periods and such, the marathon was considerably easier than the Daytona 200 miler. “Is there anything harder?” a young lad wondered.

Capability was mentioned as a prime hand in the Kawasaki position, but it must be agreed that, though rider ability was obviously a factor, the race was won by pit strategy—three pit stops for the Honda against six for the Kawasaki and five for the Suzuki. The pit strategy, incidentally, was neatly pre-arranged by the co-rider, Allan Murray. The salesman by profession had taken some time to determine fuel mileage, then sat down with a slide rule and figured out the most advantageous times to pit for fuel. Murray calculated three stops—one every 2 hr. and 15 min. Slide rule strategy paid off.

(Continued on next page)

JACK PINE

PERRY FIELDS

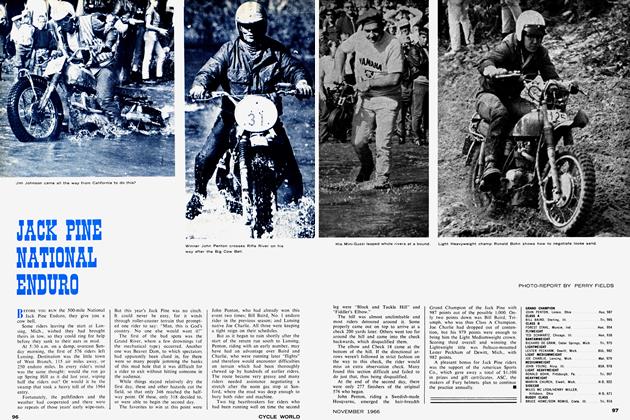

In recent years, the world famous Jack Pine 500-mile National enduro has started from the heart of downtown Lansing, Mich. For more than a third of a century, people had gathered to watch the colorful departure of riders as they headed north for the woods.

This year, however, the tradition and pomp were missing from the 41st Jack Pine run. Riders started at Reedsburg Dam, a park and camping area on the Muskegon River, five miles from Houghton Lake. The move was prompted by the limited routes that could be arranged in the traditional area. Other past pleasures that were missed were the hot dinners in the church at West Branch, the banquet, and movies that once formed part of the Jack Pine scene.

The riders’ meeting confirmed rumors that the new look Jack Pine would be tougher than ever. At 7 o’clock the next morning, a Saturday, the first six ma-

chines departed. Bikes left in groups of six every minute, until all 586 had started.

A heavy fog hung over the area as John Young of Asip, 111., carrying No. 1 plate, left the main highway for the no-man’s-land ahead. The noon stop was at Frederic, 126 miles north, over hills that a mountain goat would shun, through swamps that turned machines into globs of mud, and into woods so tight that many riders lost the skin off their knuckles when squeezing between trees.

The morning ride alone claimed more than half the starters—about 272 machines reached Frederic. After a quick meal and a brief rest, the machines headed back south. Conditions for the return ride were easier.

When results were posted at the end of the first day, the majority of the existing riders were already asleep, but their mechanics, wives and friends were waiting for the scores. Two checks were missing—it seemed the checkers had taken the reports home. Without these checks, no one knew for sure who was leading the run. Bill Baird, LeRoy Winters, John Penton, Ron Bohn and John Young were high in contention, however—particularly Baird, who had lost least points without counting the missing checks.

The skies opened on Sunday morning, and riders were treated to a downpour. The Beaver Dam was not as sloppy as it had been in previous runs. The bottom seemed harder, and the deep water gave problems. This hit riders who had not waterproofed their machines. Approximately 230 machines started the second day’s run, although the rough country before the Beaver Dam quickly claimed some of these. Not one of the powder puffs was left, while the sidecars were eliminated the

(Continued on next page)

previous day almost before the enduro started. George Wolfe, and passenger John Olson, won the sidecar championship by completing 47.2 miles.

From the Beaver Dam, riders headed for Maple Valley, 25 miles west of West Branch. This was their first fuel stop of

the morning. After passing the roller coaster sand riding at Sky Line Drive, a few miles of open trail riding, White Ash Sands, and Preachers Nob, riders reached the second fuel stop, at Clear Lake. The noon stop at Reedsburg Dam left riders with only 66 miles to the finish. Final results showed that Bill Baird had won the prized Cow Bell, with a score of 979. James McCabe, the class A champion, was closest, with 965. Bill’s win came after two near misses. In 1965 he lost to Bill Decker by three points, and in 1966 he trailed John Penton by only two points. This year, four points were the most that Baird lost at any one check. He dropped a total of 17 the first day and only four during the second.

After victories by Greeves in 1965, and Husqvarna in 1966, Triumph has reclaimed the event—no run was held last year.

The Lansing Motorcycle Club and the Jack Pine Committee received cooperation from the Houghton Lake Chamber of Commerce, Michigan State Police Post at Houghton Lake, the Sheriffs’ Departments of Missaukee, Roscommon, Kalkaska, Crawford, Lake, and Otsego counties, and the Michigan Department of Conservation.

ARNOLD LONG

Arnold Long, 31-year-old Expert No. 26P, was killed when his motorcycle struck a road sign on an interstate highway near his home at Champaign, 111. Long twice was ranked among the nation’s top 50 Experts. In 1962 and 1963, he finished 2nd in the IllinoisIndiana State Motocross Championships, and won the title in each of the following three years. The last AMA national he contested was the Peoria TT, in August.

Long worked at the Aeronautical Laboratory of the University of Illinois. He is survived by his wife, Martha, and four children.

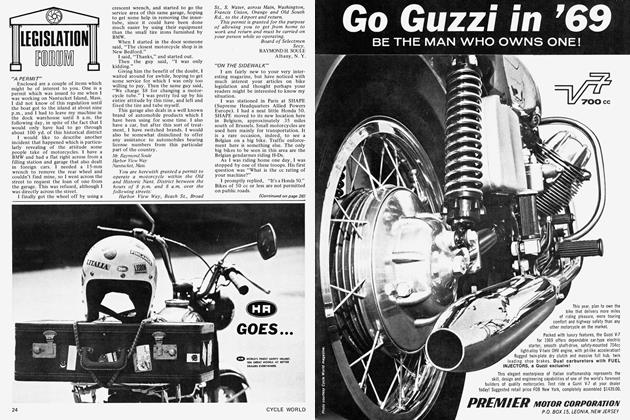

BMW WINS MARATHON

BMW machines placed 1st and 2nd in a five-hour marathon at Virginia International Raceway, Danville, Va., the first production race ever staged by the Association of American Motorcycle Road Racers.

Thirty bikes lined up for the European style push start. A 745-cc Norton Commando, co-ridden by Frank Camillieri and Andy Lascoutx, streaked into an immediate lead, and appeared destined for overall victory. But, after setting fastest lap at 74.96 mph, and dominating the race until the final hour, the Commando retired with mechanical problems.

For the closing laps, the two BMWs, ridden by Kurt Liebmann and Fred Simone, and John Potter and William van Houton, maintained the first two places. The Liebmann/Simone combination won, and the bright orange Harley-Davidson Sportster of Barry Page and Don Grubb placed 3rd overall.

The leading BMW completed 342.4 miles of the twisting 3.2-mile circuit, at an average speed of 68.42 mph.

A Suzuki won the 500-cc class, while the Terry Ernest/John Porter Yamaha beat a Kawasaki in the 350 section. The Ducati team of Walter Finnegan and AÍ Gehb claimed the 250 class, ahead of another Ducati and a Kawasaki. A 175 Kawasaki was 1st in the 200-cc division.

Twenty-two machines still were running at the finish of the race, which was supported by Sunoco and Amoco, with fuel for riders, and the Nisonger Corporation, with KLG spark plugs. [O]