MEXICO ON 500cc A DAY

OUR WITTY TRAVEL BUG RIDES AGAIN

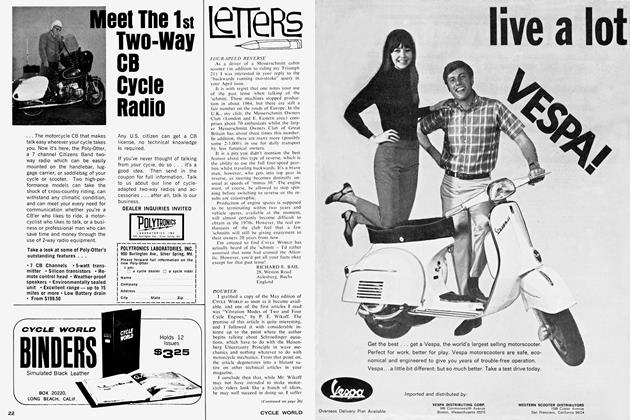

ELLIOT FRIED

IT WAS THE SOGGY month of November that I sat in my Seal Beach hovel listening to the rain pounding incessantly on the roof, dripping through the holes that I meant to patch last month.

Sipping from a freshly opened jug of Red Mountain, I rotated a small two-bit globe that stood on my desk. The world spun before me, especially after half a jug. Where to go during the coming summer? Africa? India? Australia? Downey? A few sips later, I had visions of myself complete with white jungle suit and Bell pith helmet cycling after lion, tiger, and an occasional veiled woman, my luggage carried by a train of native guides on matching Honda 50s .. .

Then, suddenly the world flew out of my hands and crashed to the floor, and I turned to face the cause of this earthshaking disaster. It was Susan.

"I told you to fix that roof. I told you!" she yelled, picking up the back issues of CYCLE WORLD that surrounded my chair and flinging them across the room. "Don't say I didn't tell you 'cause I did."

"All right, so you told me."

I dodged into the kitchen, where I tried to recapture the safari. But I couldn't, so instead I began to think . . . Shipping two people and a cycle anywhere, even to Catalina, would take funds that I didn't have.

"I walked back into the living room, side stepped Susan, and, shrugging, picked

up the world. I turned it slowly in my hands until I discovered a dent, a dent running from the green of California, deep into the orange and yellow heart of Mexico. Mexico, land of sombreros, fiestas, siestas, señoritas . . .

Susan walked by, playfully kicking me in the shins. Well, siestas, anyway.

Seven months later, when both the sky and my vision had cleared — punctured by needles, armed with halizone tablets, salt tablets, cables, spark plugs, a hard-earned $150.00 in traveler's checks, and, of course, Susan — I pointed my R-50 south on the San Diego Freeway, turned east on Highway 94, and drove to the Tecate Border Station. There we quickly discovered that though a driver's license will get you into Baja, it will not get you into Mexico proper; a birth certificate or passport is needed, neither of which we had.

Alas! Woe! Had the tour ended before it began? Were the intrepid young adventurers forced to return to their native land

due to technicalities?

Not quite. In broken English the border guard explained that although he'd like to let us in, the risk of losing his job prevented him, but perhaps a small "deposit" might . . .

"Will you take a check?" I asked.

He would. Ten dollars lighter and 10 minutes later, we coasted down the long slope into Tecate. After a few samples of the native product, we pressed on to Mexicali. A few miles later, I stepped behind a handy cactus and quickly replaced my leatherette riding pants with a pair of vented jeans, for the heat hit us like a wall; dry desert heat that was to last 1,400 miles until the humid tropical heat began.

Speeding through mile after mile of the Gran Desierto, the BMW, as always, refused to overheat. But I didn't. The hot air, made hotter by the opposed cylinders, was channeled upward by my legs past body and face — a pleasant sensation in November rains but not in the summer desert. Of course, if you have crash bars, you can brace your legs above the cylinders. But then you are out of contact with gearshift and rear brake, both of which often come in handy due to gaping chuckholes reminiscent of deeper segments of the Grand Canyon.

Day after day of silence, broken only by the steady turbinelike whine of the engine, the BMW averaged nearly 70 mpg with a near gross weight of 800 pounds, which included 125 pounds of Susan and 60 pounds of the other luggage.

Susan did come in handy, handing me the canteen each time I jabbed her in the ribs. Wonder of wonders, her talking had slowed and then had ceased completely, her only form of communication now being jabbing me back: once if she wanted me to stop, twice if she was pointing something out, thrice or more, indicating the frustration of a woman whose mouth is too dry to talk.

We cycled parallel to the American border until we reached Sonoyta where, after I dug out visas, motorcycle registration papers, and a driver's license, the guard sighed and grudgingly affixed a turista sticker to my windshield. Susan and I stood by the bike and stared across the fence at the Arizona border station, its fat gray air-conditioner bulging from its window as if trying to lure wayward citizens back to the promised land. Then we smiled at each other with chapsticked lips and turned south. After being stopped at three more checkpoints, we passed from the territory of Baja into Mexico.

Desert and more desert. I watched with anxiety as the roots of the exhaust pipes turned blue and gold. Susan thought they were pretty. Mile after mile, we rode on, refueling at the yellow pumps (which contain Mexico's highest octane gasoline) whenever we could find them. As we waited for the bike to cool, Susan and I refueled at the cantinas, where she would down three or four beers at a single sitting as I tried to master the art of drinking tequila, usually with disastrous results.

And so we continued. Susan sang and I weaved to avoid rocks, boulders, cows, goats, donkeys, ancient trucks, and tiny Islo mopeds. Soon I began weaving from force of habit, finding that the safest distance between two points was, a wavy line.

After a thousand miles of desert driving, we reached Guaymas, where I fought the desire to ride full bore into the Gulf of California. Susan had been singing "Water" into my helmet for the last hundred miles or so, off-key. Using sheer willpower, I managed to stop at the shore and we fell into the water, complete with clothing and helmets — and there we stayed for the following week.

In Guaymas, Montezuma had his first and only revenge. As I lay weak and dying, I willed my BMW to Susan. When she accepted and asked for the key, my condition immediately improved.

The next day we headed for Mazatlan, 493 miles to the south. The land was pocked by fields of crops until abruptly we were cycling through the Mexican cotton belt. Truck after truck, filled to overflowing with huge cotton bales, thundered down the narrow highway, as I followed cautiously, wondering what I'd do if that jiggling top bale suddenly toppled to the road. I was to find out sooner than I thought. For moments later, the truck ahead of me careened around a sharp turn, balanced for a sickening moment on its right set of wheels, then fell. The truck skidded along its side, tossing cotton bales like popcorn.

I slammed on the brakes, slid into a field, got off my bike and ran to the truck. But by the time I reached it, the driver had already climbed out and was inspecting the damage. He stared at me, grinning broadly, as if 1 to say that falling trucks were not especially rare in that part of the country. I shook my head in disbelief. Then I returned to my bike, pushed it back onto the road, and was out of the cotton belt by nightfall.

A few miles north of Mazatlan, we crossed the Tropic of Cancer, and as if nature paid attention to signs, the country suddenly turned lush green. In Mazatlan, the only accommodation we could afford was the beach, and there we stayed until the next day, when we cycled to a place on the opposite side of the price spectrum — the village of San Bias.

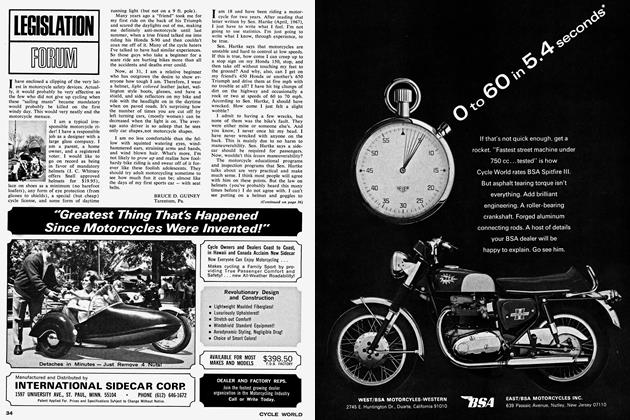

Surrounded on three sides by dense tropical jungle and on the other by the sea, San Bias is connected to civilization by a single narrow road that cuts through 30 miles of pure jungle, silent save for the screaching of invisible birds and the whack of machete against jungle. I suddenly felt as if I had entered a misplaced set from an old Tarzan movie.

The thirty miles were covered in a bit over two and a half hours! Once I had to weave through a herd of pigs driven across the road before bypassing a long, green snake, sunning himself on the asphalt. Then I spent thirty minutes bullying my way through seven guides who formed a human wall across a small bridge, insisting they take us for a canoe ride in their alligator-infested river. (If these people were living in the U.S., they'd make natural insurance salesmen.)

The Hotel Belmont in San Bias costs 72 cents for two, and that's complete with running water, a phrase which means that although you have both shower and sink, you'll have no water for them unless you run after the aged keeper shouting,"Agua, agua, por favor!" until he finally agrees to turn it on. Then you rush back to your room, peel off your clothing, and try to take a quick shower before he turns it off again. Usually the water will slow and drip to a stop just as you get beneath it. Then you dress and repeat the ritual.

Souvenirs? I bought Susan a huge iguana for a peso and placed it in her dresser drawer to surprise her. She retaliated by paying a few local kids to tie a snake around my front wheel. What a fantastic burglar device if someone could patent it! Ever try to untie a snake?

We lasted two days in San Bias before the daily heat and the nightly rain drove us out. Those who stay much longer are usually too weak to leave. Nevertheless, San Bias is one of the most interesting and inexpensive places in Mexico.

Touring from San Bias to Guadalajara, we climbed out of the tropics and into cool, dry farmland. Only five hours separate two places that have a cultural difference of perhaps two-hundred years. Guadalajara, capital of Jalisco, is a combination of the best parts of European and American cities, and its people are extremely friendly. No matter where you are in Mexico, a motorcycle is a crowd getter, and Guadalajara is no exception. This made Susan quite irritable. No woman likes playing second fiddle — even to a motorcycle.

Leaving Guadalajara, the mile-high city, we headed for Morelia, the mile and a fifth-high city, on a near-deserted road bordering the incredibly beautiful Lake

Chapala. The narrow road twisted and climbed, darting through town after tiny town. (The three things that all Mexican towns have in common are: l.They have at least one square, always graced by a fountain — or at least water tap. 2. The plaster buildings are inevitably crumbling. 3. The town is barraged by Coke and Pepsi signs, used jointly as advertisement and patching material.) In the town of Oquroga, I met an aging ex-patriot who was convinced that Coke and Pepsi were taking over the world.

"Don't tell anyone I said so," he pleaded, "or I'm done for." Leaning forward in his wicker chair, looking me straight in the eye, he inquired, "You're not a Coke man, are you?"

"No," I replied. "I never touch the stuff."

He breathed a sigh of relief. "Good.

Then there's hope."

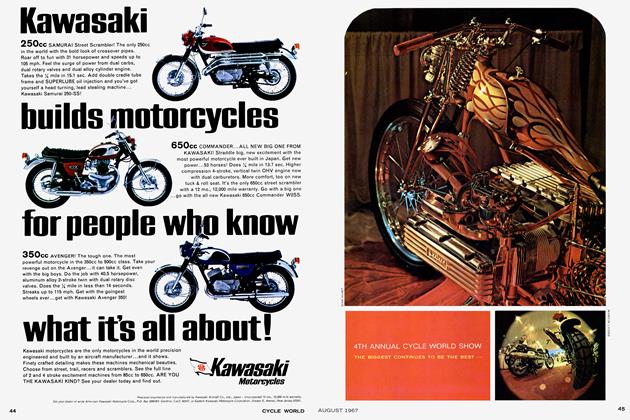

* * *

The drive from Morelia to Mexico City offered the most spectacular scenery of the entire trip. The road climbed past the nine-thousand foot mark before dropping down to Mexico City, two thousand feet below. In the space of a very few miles, the narrow road takes 310 turns across the high mountain ridge of the Sierra of Ozumatlán before dropping into thick virgin woods. For me it was the epitome of touring, a time when all the stock clichés about the merging of man and machine come true, a sensation as beautiful as it is rare.

Few Mexican highways have medians, and the truck drivers are notoriously poor at judging their share of the road. However, the closer one gets to Mexico City, the better the road becomes. The last 40 miles were covered on a four-lane divided highway. After 2,000 miles of narrow twolane road, I greatly realized how both boring and safe these highways really are.

Somewhere between Morelia and Toluca spurts the "Fountain of Youth" that Ponce de Leon missed by a bit more than 3,000 miles. The fountain is the main attraction of a small health spa appropriately named Agua Blanca. If you find it, spend a night. The owner runs Agua Blanca as a hobby, so it's virtually unadvertised. Here you have the dubious honor of swimming in the world's most radioactive water. Even though you may not come out years younger and quicken feminine pulses, you'll at least quicken geiger counters.

Our super health came in handy the next day on the road. Caught in a sudden cloudburst, we soon discovered that our warsurplus waterproof matches weren't waterproof, so we placed the cover over the bike and hid within it, quivering at every thunderclap. As the rain slowed, we pressed on — soggy but undaunted. Thirty miles outside of Mexico City, we ran into hailstones the size of shooter marbles. Hailed into a ditch, we again cowered beneath the cover, like two kids hiding beneath a bed. When the hail stopped and a steady drizzle began, we finally made it into the big city, where we were immediately run off the road by incessant and insane traffic.

Mexico City is fine for those who have a fair amount of money and who are attracted to fast city life. We weren't, and our funds were rapidly disappearing. One of the best things about Mexico City is that it's completely overrun by mariachi bands, groups of musicians as loud as they are bad, who will serenade you anywhere (restaurants, buses, parks, alleys) for an incredibly low price. If you feel extravagant, hire them for a day as you would a car; they'll follow you anywhere, their quality of music rising in direct proportion to the amount of drinks with which you ply them.

We left Mexico City within a week. Once you're on the road for any length of time, it's awfully hard to stay off it.

Heading north on the Pan American Highway, we drove through rich farmland, an extremely intensive stretch of mountains, more tropics, and then mile after mile of flat semi-arid desert. But before we leave the mountains forever, we must not forget the donkey.

As we were climbing through the mist 200 miles south of Ciudad Victoria, Susan was singing in her own inimitable way, which I thought was enough to scare anything off the road. Then suddenly I saw a donkey, looking big as a house and twice as sturdy, standing in the middle of the road. I stared at him and he stared back. I swerved but he moved. I swerved the other way but he moved back and stopped. I honked, Susan screamed, the donkey brayed. Then I hit the brakes, but it was too late for all at once there was donkey everywhere. My fairing brushed along his side like a huge back scratcher, and then we were past. I drove on, too shaky to stop. When I looked back, all I could see was mist.

"Did that really happen?" Susan asked.

"I'm not sure. I think it did." But it was only at the next stop, when I picked brown hair from the mist-wet fairing, that we were certain.

In our last night in Mexico, I was almost arrested. Susan and I were walking through the square of a small town 200 miles south of the Texas border. Thick streams of birds flowed through a lemon-tinted sky. It was sunset. The town was so still one could almost hear it breathing, sighing, and in a moment of tequila-inspired enthusiasm, I kissed Susan on the cheek. Three seconds later, I was looking into the weathered face of a tall, aging man who was dressed all in black except for his shining silver pistols.

I suddenly knew what countless badmen must have felt like "fessing up" to the Lone Ranger. I understood that he was enraged, but I didn't understand why until a local barber came to the rescue and, in broken English, explained that one just doesn't do things like that in a small town, and that if I didn't want firsthand information about what Mexican jails are really like, the best thing to do would be to leave town immediately. The sheriff was muttering, and by this time, half the townfolk had poured into the square, taking bets, perhaps on the gringo against the home town champ — who by this time was restlessly stroking his holster.

We were on the road within three minutes and didn't stop until we reached

Brownsville, three hours later.

* * *

Compared to our Mexican travels, the journey back, by way of St. Louis, was quite uneventful; not a single mule was grazed. However, our monetary supply was quickly grazed into nonexistence. In other words, by the time we reached St. Louis, we were flat broke. However, we soon found work in a drive-in restaurant. I prepared malts and shakes behind the counter and Susan carried them out to the cars. Although I tried to explain to the owner how such seasoned travelers as Susan and myself should assume managerial positions, he didn't seem to understand. Three days after we began, Susan spilled a chocolate malt down a man's back, and when I attempted a refill, the malt machine exploded, sending a thick brown spray the length of the restaurant.

We headed for Seal Beach the next day and were home within a week. Our total mileage was a bit over 6,200 miles, and our total expenditure was a bit under $200.

Now, with the touring memories of last summer fresh in my mind, I sit in my Seal Beach hovel and ask myself the all-important question: Where to go this coming summer? Where?