"THE BUG MEETS THE FLY"

ELLIOT FRIED

THE BMW BUG bit me the first time one of those massive black machines silently passed my laboring Honda and sped into the horizon, its owner completely confident about the miles of desert driving ahead. I fearfully listened to every squeak, rattle and whimper, and estimated distances to the next ten service centers. I’d had the BMW bug for years, but it wasn’t until early summer that the Honda and I parted company in New York in favor of the BMW. I persuaded my friend Bill to do the same with his Lambretta. Fourteen hours after a final visit to the distributor, we were waiting in the Munich BMW waiting room, thanks to Icelandic Airlines, a German express train, and a streetcar. We paced the floor like expectant fathers, and when we were finally led to our two R-50s, cellophane still covering the SachsMeyer saddles, I felt like passing out cigars.

“Gut, ja?” asked a mechanic, wiping a speck of dust from the pinstriped front fender. Bill and I stared at the machines and said in unison, “Ja, gut.” Then we checked the gas supply, started the engines, shook hands with the mechanic, and rode out of the factory.

1 was just turning into the street when the engine sputtered and died. I calmly got off, pushed the R-50 on its stand, and kicked it over. Nothing. I tried again. Silence. After a few more violent but unsuccessful efforts, I stormed back into the factory, ready for a quick refund, wondering if my Honda had been taken off the lot. I half dragged the mechanic to my machine. He looked at it, turned a small lever beneath the tank, and kicked it over. I climbed back onto my idling mount, wondering how to say “I’m sorry” auf Deutsch. I tried to smile.

“Gute Reise,” the mechanic said, adding “Auf Wiedersehen.”

“Auf Wiedersehen,” I replied, and caught up with Bill, who was waiting for me at the corner. He was laughing so hard that he almost dropped his bike. “Do you know what happened?” I asked.

“Sure. Your fuel was off.”

“If you knew, why in the world didn’t you tell me?”

Bill looked at me and smiled. “You never asked.”

We fought our way through rush hour Munich traffic and into the country, trying to -get the feel of our machines. We were paying so much attention to shifting and throttle that we promptly got lost and ended up in a garbage dump. An old man was poking at a small, but overwhelming rubbish fire. I poked through my EnglishGerman dictionary, practiced to myself a few times, and then asked, “Wo ist die Strasse nach München?”

The man turned from the fire and stared at me. “Go back and take the fourth street on your right. You can’t miss it.”

“How . . . how did you know we weren’t German?” I stammered.

“Oh, just luck.”

It turned out that he spoke better English than we did, a situation we were not to find uncommon throughout Europe. He invited us to his house where we had our first experience with Bier; our second and third soon followed at a Gasthouse on the way back.

At first it was a strange feeling to pull into a filling station and have everyone from children to senior citizens gather around our machines and fire questions that ranged from compression ratio to curb weight, but after awhile we expected a crowd and, thanks to our trusty owner’s manuals, were ready for the onslaught. However, I was not prepared for one rather well proportioned Fraulein who whispered in my ear, “BMW absteig und geh” (roughly meaning “BMW gets up and goes,” but it rhymes in-German), giggled, and ran away.

The first leg of our journey took us to Salzburg by way of Innsbruck, the idea being to break the machines in over the Alps. With no posted speeds on the Autobahns, the Mercedes flew by at well over a hundred as we gradually nudged up to fifty. E-17, between Innsbruck and Salzburg was flooded in many places, forcing us through fields and trails. We pulled into the city feeling like seasoned travelers. We had conquered the Anstrian floods; our next quest was to conquer Salzburg Castle.

We left our bikes in the square and began our crusade through the small twisted streets, leaping fences, our coats of mail (almost) gleaming in the sunlight, panting somewhat in spite of ourselves. The castle loomed above us. Suddenly I saw her. Blonde, fair, she was standing on a turret and staring at us, her blue eyes wide with fear. A maiden in distress!

“Don’t worry, we’re coming,” I shouted, as we rushed to the castle gates. Bill got a head start. “I saw her first,” I warned him.

“Prove it,” he said, widening the gap between us.

I lowered my head and ran faster, determined to help her before Bill helped her. Neck and neck, we rounded the final corner. When the Fraulein saw us running towards her, panting, she looked even more frightened. In fact, she screamed.

“Don’t worry,” I shouted. “We’re here to help you.”

She screamed again. Suddenly, as if he sprung from a trap door, her huge mate was beside her. “Was ist los?” he yelled.

“Nothing. I thought she ... I mean we thought . . . maiden . . . distress.” It was much easier running downhill. It is rumored that the castle has never been stormed successfully.

Crossing a section of the Alps on our way to Zurich, we saw countless Mopeds with two on, climbing the grades in first gear. Husbands and wives, sons and lovers, sharing 50ccs over the peaks, and from the way their faces were set in grim determination, it was not the first time.

It was in Nürnberg that I first drove on wet cobblestone streets; it was also in Nürnberg that I first blessed the man who invented crash bars.

Speeding northward out of Kassel on a small road, I noticed how the farmhouses were getting progressively shabbier. The people in the fields were waving at us almost frantically. Bill and I waved back until the road suddenly ended, a large VERBOTEN sign signifying its termination as did barbed wire and another sign, Caution, Minefield.

“Your field?” asked Bill.

Before I could think of an adequate response, I noticed a small green figure on the other side of the field, perhaps twohundred yards away. His arms, one of which carried a long black object, were waving above his head. If he was shouting, we never heard him, for we drove back before words, and we hoped, before bullets could reach us. From then on, we paid much more attention to our maps.

Before ' jumping over to England, we rested for a few days in the Netherlands, the only country with three sets of roads: one for pedestrians, one for cars and large motorcycles, and one for bicycles and 50cc machines. It was in this land of windmills and extremely chubby women that we ran into a 50cc ratpack, Hell’s Angels on Mopeds. Fifteen or twenty of them tore through the streets of a small town outside of Rotterdam, mufflers removed, pipes belching bluish smoke. Children were whisked upstairs; shutters banged shut. The Moped boys stopped and watched us go by and then returned to their games. In my rear view mirror, I could see a thin cloud of blue smoke rising above the town.

Off to England, land of Mods, Rockers, and rain. I had heard the usual jokes about English weather, but had never believed them until halfway across the Channel from Ostende, I saw black clouds hovering above the water.

“Looks like a storm,” I commented to the passenger next to me.

“On the contrary,” he said, filling his pipe. “That’s England.” (Continued)

In my nineteen days in England and Scotland, it rained fully or partially for seventeen of them. After a few days, we began to accept the rain as perfectly normal, and the two dry days seemed strange. Each day Bill and I would cycle for fifty miles, wring each other out, and then cycle for fifty more. Due to our large machines and black riding jackets that we needed for survival, we were sure we would be identified as Rockers and so were wary of any scooter that passed our way. We smiled and waved at all of them, trying to show them that we were friendly. Often the scooterist would see these two large machines approach him, the drivers grimacing and waving, and he would take the quickest turn-off, looking somewhat like the apprehensive maiden of Salzburg, whose vision still haunted me, especially when I had an extremely large supper.

England is the land of big cycles, and perhaps one out of every four or five of these, scooters included, has a sidecar. It isn’t surprising to see mom, dad, and two or three kids stuffed in or onto the threewheeled beast, off for a spin in the country. In Carlisle, I met a devoted enthusiast who said that his wife gave him a choice between her or his machine. He filed for divorce within two days. I commended him on his fine choice and drove off, needless to say, in the rain.

It is only in England, I thought, that one is not allowed the privilege of hostelling, if one uses a self-propelled vehicle. So every evening Bill and I hid our machines under a convenient tree, slung our packs upon our backs, and ran the final quarter mile to the hostel.

“My, you chaps look bushed. Hard day on the road?”

“Yes sir.”

Soon we got so good at it that we began believing it ourselves, hiking one morning for three miles before we remembered that we did have cycles, and then hiking back to get them. It was only during the latter part of our stay that we discovered that one could hostel with motorized vehicles, as long as one didn’t use them at the hosteling site. However, if it weren’t for our subtle deception, we would never have met the bobbie in Colchester who helped us break in. One night we had cycled too late to walk the final distance to the hostel before closing time, not knowing we could have cycled to the door. Remembering that I read somewhere that bobbies are supposed to be quite helpful and because, strangely enough, it was raining, I stopped next to a patroling bobbie and asked him to help us. He led us to what we thought would be jail, but what turned out to be a deserted house from which he gently pried the padlock from the door.

“I think you lads will be safe in here tonight. I’ll come and wake you in the morning before anyone comes. Sleep well,” he said, and went away. Bill and I pinched each other and then, due to a hard day’s cycling, fell asleep. The next thing I knew, someone was touching me on the shoulder.

“Morning, lads. Sleep well?”

After we assured him that we did, he took us to the station, let us wash, and gave us a cup of tea. Bill and 1 pinched each other again and then drove southward to Dover, where we caught a ferry for Le Havre. Halfway across the Channel, something appeared in the sky. I asked Bill what it was.

“I’m not sure,” he replied, “but I think it’s the sun.”

France was a land of beautiful countryside and an endless amount of cafes which were really bars. Nobody eats in France. France was a week of French bread and wine. Bill and I got about sixty miles per loaf/liter. All in all, the people seemed quite aloof compared to the Germans and the English, except for the one time we were passing through Saumur, when it seemed that the whole town, waving and gesturing, turned out to meet us. Bill and I waved back. They waved more frantically and so did we, until we heard a loud whirring sound. We pulled off just before the stream of bicycles pouring down the road drowned us. We proceeded again, only to have the same thing happen a few miles later. Tired of bread, wine and bicycles, we entered Spain.

South of San Sebastian, the traffic thinned, as did the roads. We proceeded to Miranda del Ebro, where we pampered ourselves in a luxury hotel, $2.25 a night, including meals. A bottle of good Spanish beer costs eight cents. Taking the donkey express to the outskirts of town, I walked through fields still cultivated by hand and watched a steam-engined freight train climb the steep grade to the south. I felt as though I were transported back through time, though not knowing where.

I had purchased a two liter bota, which proved to be extremely handy. “Wine stations” are much more numerous than gas stations, the latter sometimes being as much as a hundred miles apart. Like everywhere else in Europe, gasoline was extremely expensive (around 80d per gallon) and the highest quality Spanish gasoline was barely a match for our discount station brews. At one wine stop bordering the desert, we were joined by an R-26 mounted policeman who examined our machines in detail, and then filled my bota, demonstrating with complete proficiency its proper use. Again the topic of motorcycles helped to bridge the language barrier; there’s so much one can say with one’s hands or show with a stick in the dirt.

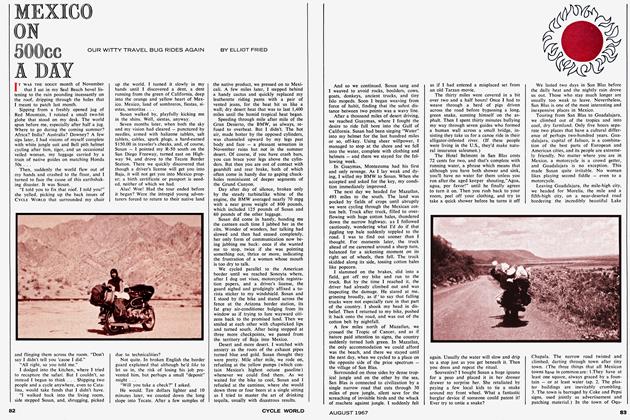

I hung the near-empty bota around my neck. Then Bill and I drove into the intense heat of the desert, where through the dust and glare, the images of people threshing grain by hand, chained mules walking laboriously in circles, and the tall foreboding churches seemed like pages from a picture book. The sun we had never seen in England was making up for lost time, and although our bikes never overheated, we often did.

Flies had become our constant companions, and we had soon ceased to notice them. In Zafra there was one particular fly who gave me an extremely nasty look just before he bit me. I have no way of proving it, but I think that many of the incidents that occurred south of Zafra were a result of this particular fly.

We cycled past Sevilla and into Algericas, where Bill had to be rescued from a Spanish Inquisition rerun (I never dreamed that cycles would be considered controversial), and crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to Tangier, land of veiled women, prepubertal opium pushers, and the infamous Black Market. I exchanged my remaining travelers checks into durmas on the market, getting six durmas ($1.20) for every dollar I exchanged. However, there was one catch. Durmas cannot leave the country. It was not pangs of righteousness, but rather pangs of something else that was to soon cause me to regret my exchange.

It happened the third night. I awoke in our room in the Hotel Williams, shivering, yet drenched in sweat, and listened to Bill snoring across the room. My mouth was dry and it was hard to speak. “Bill,” I whispered. Then everything turned black.

Later, “Malaria,” said the doctor, standing above me. “Five dollars.”

I rubbed my forehead. “Can I pay you in Durmas?”

“Five dollars.”

Before things turned black again, I found out that Bill had also played the Black Market game. When I awoke, the doctor, Bill, and my Durmas were gone. I lay in the bed thinking how my friends in California would laugh when I’d tell them how I got malaria from a Spanish fly. Bill soon returned with a coke and a ticket for me and my bike on a Yugoslavian freighter, the Tiihobic, which would be sailing from Casablanca to New York.

“There’s only one catch,” Bill said. “It’s leaving tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow? But how can I ... ?”

“Don’t worry. You’ll get there.”

It was still dark when he led me to the garage, started the engine, and helped me on to my machine. He was about to start his own when he noticed that his rear tire was flat. “Looks like you’ll have to make it on your own.”

I flicked on the headlight and drove into the night, catching Route 2 to Casablanca. I wish I could sort out what I saw from what I thought I saw, but the fever made that impossible. I remember weaving through a herd of camels and waving to old ladies selling flowers in the desert. South of Asilah, I watched the sunrise and saw hundreds of tiny round huts nestled in the sand. Six hours and 384 kilometers after Tangier, I was in Casablanca. I was aboard the Tiihobic in fifteen minutes, watching my BMW being lifted fifty feet into the air by what seemed no more than a fish net.

As soon as we left the harbor, I rushed to the ship doctor’s quarters, knocked on the door, and burst in without waiting for a reply. The doctor jumped from his chair in surprise.

“Malaria,” I gasped. He led me into sick bay and gave me a shot of quinine so large I slept on my stomach for a week.

Finding myself to be the only passenger, I spent the next nine days playing chess with the 56 Yugoslavian non-English speaking crewmen and driving the BMW around the cargo area.

As my mind cleared, the memories of Europe and Morocco became sharp and clear. Before we docked in Brooklyn, I was already homesick for a dozen countries and was in the process of planning my return, armed with my trusty road maps and a large supply of quinine. For I’ve found that once one gets the bug, it’s very hard to lose it.