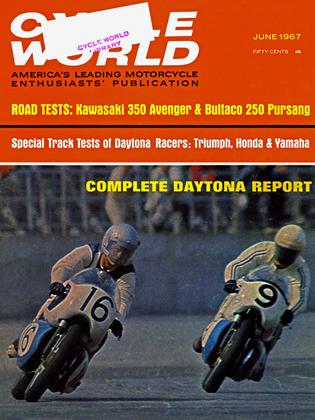

A LOOK AT DOUG HELE

TRIUMPH'S DEVELOPMENT ENGINEER

B. R. NICHOLLS

"SUCCESS is one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration." So says a book marker sent by Al Stuckey, Pat Owens and Jack Wilson of Johnson Motors to the occupant of a first floor office at the Triumph works in Meriden, Conventry. It is not a big room. In one corner stands a drawing board, in another, a bookcase. Spread around are bits and pieces of engines - Triumph engines. On the outside the door is labeled simply "D. L. Hele."

That is the name behind the success of Triumph machines at Daytona, it is the name of the 47-year-old Englishman who spent his time there with stop watch and pencil noting everything about six Triumph machines and quite a few things about the opposition. To those on the spot he may have seemed uncommunicative, retiring or shy, but the simple answer is Doug Hele went to Daytona as architect for a Triumph victory.

Success has to be built on a firm foundation of both theoretical and practical knowledge. This is where Doug Hele scores over so many other development engineers, for he covers around 10,000 miles a year on bikes, in particular, those with a problem to be solved. He was apprenticed for five years to the British Motor Corporation in machine tool design and the drawing office and worked with them as a draftsman until 1945. Since Doug could not get onto the design side, he joined the now defunct Douglas concern and did the original sketch of the radiadraulic fork and worked on its components, but had nothing much to do with the engines, which he was really after.

At that time, it was his ambition to join Norton on the design and development side, and he achieved this in 1947, working with Joe Craig and Bert Hopwood. Then Hopwood went to BSA, and in 1949, he asked Hele to join BSA to design and build a 250cc racer. This in itself could well be the subject of another article; suffice it to say at this stage that two years were spent on a completely new design, not only the single cylinder ohc, four-valve, twin-carburetor engine with outside flywheel, but also the frame and suspension. It was built in 1951 and after a couple of years development, produced almost 30 bhp. With Geoff Duke on board it equalled the Oulton Park class lap record in secret tests, but a directional requirement before racing of a guarantee to win meant the project was shelved. A look of "99 percent perspiration" appears as Doug recalls that particular decision.

In 1956, he went back to Norton with a free hand as development engineer on the .Manx models. There, he had a great deal to do with the design of the Jubilee. At that time, the 500 and 650 Dominators, which Hopwood had designed back in 1947, were not very quick; the Manx engine was giving bevel trouble, which he immediately cured by using the design that appeared in his 250cc BSA. Hele learned a lot during 1957 and '58 from engines left by Joe Craig, not the least being that bhp is just as necessary at 6,400 at it is at 7,400. In 1957 he started development on the 500cc Dominator twin, using Manx type cams with a ramp, and by 1961, had the engine turning out 52 bhp with very good torque from 5800 to 7400 rpm. That year, Phil Read was set to ride it in the Senior TT, but fell off in practice, and Tom Phillis rode instead. Nineteen-inch wheels were used and half a link had to be added to the chain to gain sufficient clearance; but even so, the tire touched the frame at the bottom of Bray Hill and smoke can just be detected in the photo of Phillis at that spot during his memorable 100 mph lap. That, done in 1961, is still the only twin and only push rod engine to have lapped the Island at over the "ton."

This was a peak period of development at Norton, for that year, in the Thousand Kilohneter race at Silverstone, they took the 350, 500 and 650 classes. Speed for the 650 had been obtained by a head Doug redesigned in 1957, to allow Amal GP carburetors. Then, in 1962, the Yanks had a yearning for 750s, so the 650 was bored out to 73mm to accommodate the taste.

Meanwhile, other work had been going on, namely a desmodromic idea Doug had worked out before going to Norton, and Bob Mclntyre practiced on it on the final TT practice morning of 1960, but it didn't have the torque of a conventional Manx. A 350cc desmo in 1961 lacked a good compression ratio. A 500 top on a 350 was tried but not raced. The difficulty was to get accurate cams for the desmo. Also, it broke vertical shafts and this led to an improved design for the Manx engine. In an attempt to shorten the stroke, a 93mm bore engine was tried. However, it required a narrower valve angle, so it was dropped.

Then, in 1962 came the move south to London, so that all could be under the AMC roof at Plumstead. Doug Hele toyed with the idea of joining the Ford Motor Company or teaching technical drawing, which he had previously done part time. However, motorcycle engines were his life, and late in 1962, Doug joined Triumph, in charge of development where he renewed his association with Bert Hopwood.

The first problem Doug tackled was cam wear on the unit construction 650, which was already a good motorcycle as a result of design work by Brian Jones and development by Frank Baker. Doug overcame the problem by using bigger

(Continued on page 101)

cams, while at the same time employing barrel type push rods to cut out side whip. Power was very good on open megaphones, so to get the same with mufflers, a balance pipe and 1 VA -inch pipes instead of II/2-inch were used with special silencers.

Doug did not ride in his first few months at Triumph, but when he did, he fully understood the problem facing Percy Tait, the development rider who raced the machines. To cure the handling misdemeanors, he felt that more trail with the existing wheelbase was required. This was achieved by taking 0.775 inch out of the top tube and altering the head angle. This also gave a lower center of gravity. Then, for racing in 1964, the top yoke was altered slightly, fork movement lengthened, and the handling problem was solved. The back end had not been touched, apart from the rate of dampening.

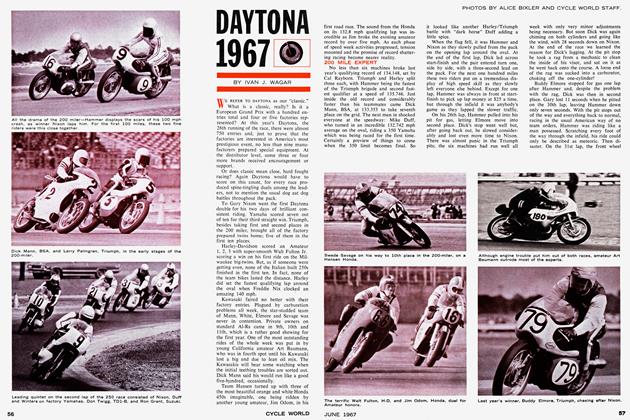

In September, 1965, it was decided to race at Daytona in 1966, so Rod/Coates and Cliff Guild went to Meriden to give the lowdown on the American scene. It was notebook, stop watches and coats off in 1965, for they had their problems in practice from which a lot was learned. But it was worthwhile — Buddy Elmore won.

"We learned from each other on that trip," says Doug, "not the least being the use of hard-faced cams which Cliff Guild had been using. It pays to have the same size cams at the end of the race as you start with."

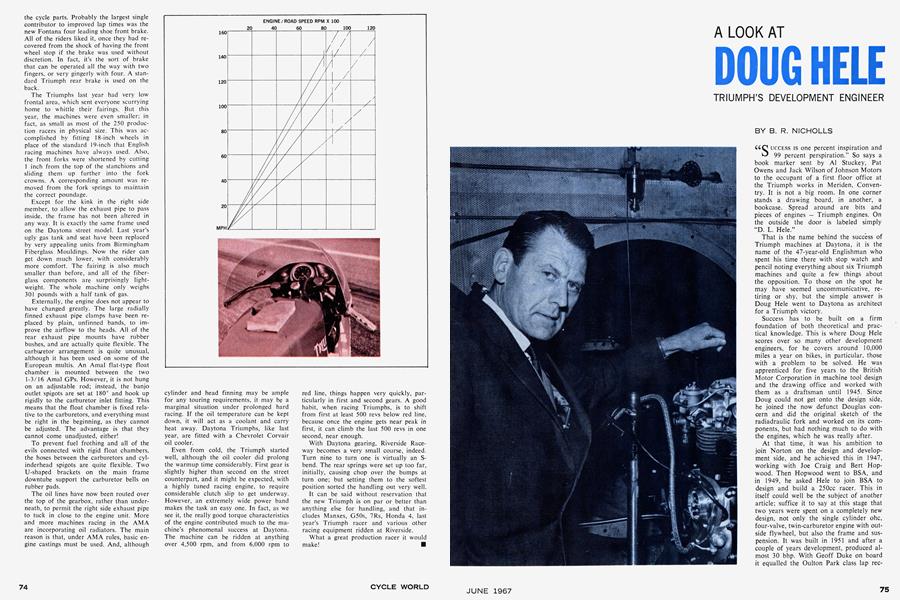

The story of the 1967 races is told elsewhere, but it is worth noting that Triumph went to Daytona with 18-inch wheels which were not too popular. A change at the back to 19 saw three seconds knocked off lap times in practice.

"You cannot argue that 18-inch wheels should be all right when a rider can give that sort of answer," says Hele. When asked if any down-field runner had impressed him, he opted for Gene Romero, whose machine was not really right in practice and possibly did not get all the attention it deserved. But the bike was put right by race time and Doug is pretty sure he'll be among the leaders in 1968.

That brings us to next year, when Doug hopes Triumph will go back to try for three in a row.

"By then we will need more power to pull a higher gear, assuming Harley does some work in the meantime,"claims Hele. "Rockers, cams, combustion chambers are the avenues of approach, and we shall also redesign the exhaust mounts, particularly at the engine end."

It will be a diligent search for more power, as Doug Hele is a chartered engineer who expended a lot of perspiration getting his A.M.I. Mech. E. (Associate Member of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers).

Squish heads and all that? A brief grin appeared on Doug's face as he countered, "The Domiracer did not need that in 1961."

You can bet your life the old saying is wrong. There will be more than 1 percent inspiration from this man before practice starts for Daytona in 1968. ■