Wire Wheeled Pronghorn Hunt

ALFRED H. MILLER

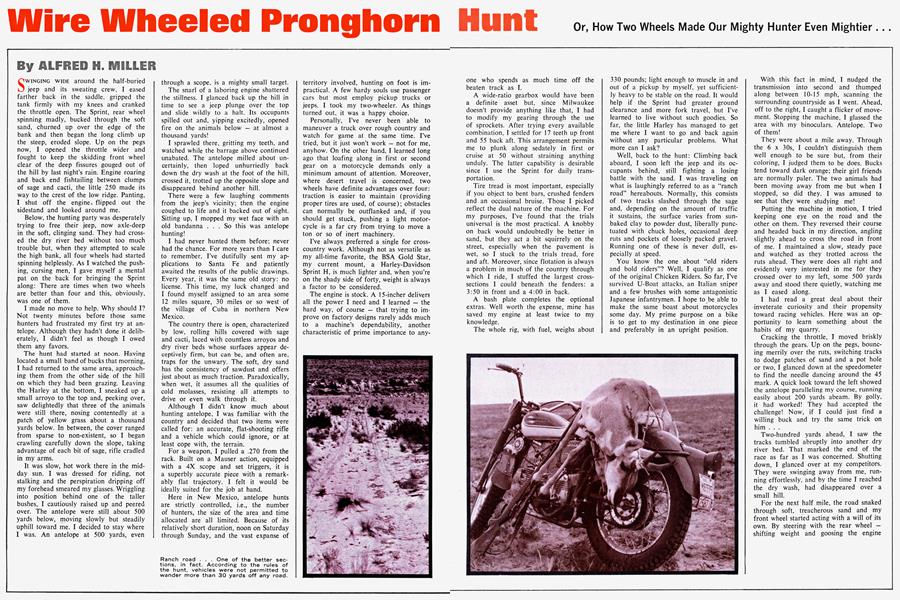

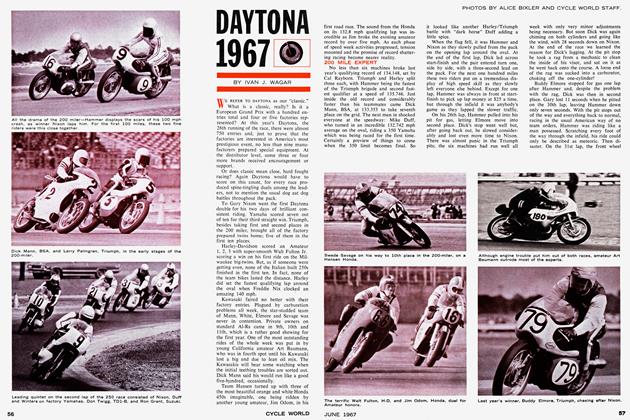

SWINGING WIDE around the half-buried jeep and its sweating crew, I eased farther back in the saddle, gripped the tank firmly with my knees and cranked the throttle open. The Sprint, rear wheel spinning madly, bucked through the soft sand, churned up over the edge of the bank and then began the long climb up the steep, eroded slope. Up on the pegs now, I opened the throttle wider and fought to keep the skidding front wheel clear of the deep fissures gouged out of the hill by last night's rain. Engine roaring and back end fishtailing between clumps of sage and cacti, the little 250 made its way to the crest of the low ridge. Panting, I shut off the engine, flipped out the sidestand and looked around me.

Below, the hunting party was desperately trying to free their jeep, now axle-deep in the soft, clinging sand. They had crossed the dry river bed without too much trouble but, when they attempted to scale the high bank, all four wheels had started spinning helplessly. As I watched the pushing, cursing men, I gave myself a mental pat on the back for bringing the Sprint along: There are times when two wheels are better than four and this, obviously, was one of them.

I made no move to help. Why should I? Not twenty minutes before those same hunters had frustrated my first try at antelope. Although they hadn't done it deliberately, I didn't feel as though I owed them any favors.

The hunt had started at noon. Having located a small band of bucks that morning, I had returned to the same area, approaching them from the other side of the hill on which they had been grazing. Leaving the Harley at the bottom, I sneaked up a small arroyo to the top and, peeking over, saw delightedly that three of the animals were still there, nosing contentedly at a patch of yellow grass about a thousand yards below. In between, the cover ranged from sparse to non-existent, so I began crawling carefully down the slope, taking advantage of each bit of sage, rifle cradled in my arms.

It was slow, hot work there in the midday sun. I was dressed for riding, not stalking and the perspiration dripping off my forehead smeared my glasses. Wriggling into position behind one of the taller bushes, I cautiously raised up and peered over. The antelope were still about 500 yards below, moving slowly but steadily uphill toward me. I decided to stay where I was. An antelope at 500 yards, even through a scope, is a mighty small target.

The snarl of a laboring engine shattered the stillness. I glanced back up the hill in time to see a jeep plunge over the top and slide wildly to a halt. Its occupants spilled out and, yipping excitedly, opened fire on the animals below — at almost a thousand yards!

I sprawled there, gritting my teeth, and watched while the barrage above continued unabated. The antelope milled about uncertainly, then loped unhurriedly back down the dry wash at the foot of the hill, crossed it, trotted up the opposite slope and disappeared behind another hill.

There were a few laughing comments from the jeep's vicinity; then the engine coughed to life and it backed out of sight. Sitting up, I mopped my wet face with an old bandanna ... So this was antelope hunting!

I had never hunted them before; never had the chance. For more years than I care to remember, I've dutifully sent my applications to Santa Fe and patiently awaited the results of the public drawings. Every year, it was the same old story: no license. This time, my luck changed and I found myself assigned to an area some 12 miles square, 30 miles or so west of the village of Cuba in northern New Mexico.

The country there is open, characterized by low, rolling hills covered with sage and cacti, laced with countless arroyos and dry river beds whose surfaces appear deceptively firm, but can be, and often are, traps for the unwary. The soft, dry sand has the consistency of sawdust and offers just about as much traction. Paradoxically, when wet, it assumes all the qualities of cold molasses, resisting all attempts to drive or even walk through it.

Although I didn't know much about hunting antelope, I was familiar with the country and decided that two items were called for: an accurate, flat-shooting rifle and a vehicle which could ignore, or at least cope with, the terrain.

For a weapon, I pulled a .270 from the rack. Built on a Mauser action, equipped with a 4X scope and set triggers, it is a superbly accurate piece with a remarkably flat trajectory. I felt it would be ideally suited for the job at hand.

Here in New Mexico, antelope hunts are strictly controlled, i.e., the number of hunters, the size of the area and time allocated are all limited. Because of its relatively short duration, noon on Saturday through Sunday, and the vast expanse of territory involved, hunting on foot is impractical. A few hardy souls use passenger cars but most employ pickup trucks or jeeps. I took my two-wheeler. As things turned out, it was a happy choice.

Personally, I've never been able to maneuver a truck over rough country and watch for game at the same time. I've tried, but it just won't work — not for me, anyhow. On the other hand, I learned long ago that loafing along in first or second gear on a motorcycle demands only a minimum amount of attention. Moreover, where desert travel is concerned, two wheels have definite advantages over four: traction is easier to maintain (providing proper tires are used, of course); obstacles can normally be outflanked and, if you should get stuck, pushing a light motorcycle is a far cry from trying to move a ton or so of inert machinery.

I've always preferred a single for crosscountry work. Although not as versatile as my all-time favorite, the BSA Gold Star, my current mount, a Harley-Davidson Sprint H, is much lighter and, when you're on the shady side of forty, weight is always a factor to be considered.

The engine is stock. A 15-incher delivers all the power I need and I learned — the hard way, of course — that trying to improve on factory designs rarely adds much to a machine's dependability, another characteristic of prime importance to anyone who spends as much time off the beaten track as I.

Or, How Two Wheels Made Our Mighty Hunter Even Mightier...

A wide-ratio gearbox would have been a definite asset but, since Milwaukee doesn't provide anything like that, I had to modify my gearing through the use of sprockets. After trying every available combination, I settled for 17 teeth up front and 55 back aft. This arrangement permits me to plunk along sedately in first or cruise at 50 without straining anything unduly. The latter capability is desirable since I use the Sprint for daily transportation.

Tire tread is most important, especially if you object to bent bars, crushed fenders and an occasional bruise. Those I picked reflect the dual nature of the machine. For my purposes, I've found that the trials universal is the most practical. A knobby on back would undoubtedly be better in sand, but they act a bit squirrely on the street, especially when the pavement is wet, so I stuck to the trials tread, fore and aft. Moreover, since flotation is always a problem in much of the country through which I ride, I stuffed the largest crosssections I could beneath the fenders: a 3:50 in front and a 4:00 in back.

A bash plate completes the optional extras. Well worth the expense, mine has saved my engine at least twice to my knowledge.

The whole rig, with fuel, weighs about 330 pounds; light enough to muscle in and out of a pickup by myself, yet sufficiently heavy to be stable on the road. It would help if the Sprint had greater ground clearance and more fork travel, but I've learned to live without such goodies. So far, the little Harley has managed to get me where I want to go and back again without any particular problems. What more can I ask?

Well, back to the hunt: Climbing back aboard, I soon left the jeep and its occupants behind, still fighting a losing battle with the sand. I was traveling on what is laughingly referred to as a "ranch road" hereabouts. Normally, this consists of two tracks slashed through the sage and, depending on the amount of traffic it sustains, the surface varies from sunbaked clay to powder dust, liberally punctuated with chuck holes, occasional deep ruts and pockets of loosely packed gravel. Running one of these is never dull, especially at speed.

You know the one about "old riders and bold riders"? Well, I qualify as one of the original Chicken Riders. So far, I've survived U-Boat attacks, an Italian sniper and a few brushes with some antagonistic Japanese infantrymen. I hope to be able to make the same boast about motorcycles some day. My prime purpose on a bike is to get to my destination in one piece and preferably in an upright position. With this fact in mind, I nudged the transmission into second and thumped along between 10-15 mph, scanning the surrounding countryside as I went. Ahead, off to the right, I caught a flicker of movement. Stopping the machine, I glassed the area with my binoculars. Antelope. Two of them!

They were about a mile away. Through the 6 x 30s, I couldn't distinguish them well enough to be sure but, from their coloring, I judged them to be does. Bucks tend toward dark orange; their girl friends are normally paler. The two animals had been moving away from me but when I stopped, so did they. I was amused to see that they were studying me!

Putting the machine in motion, I tried keeping one eye on the road and the other on them. They reversed their course and headed back in my direction, angling slightly ahead to cross the road in front of me. I maintained a slow, steady pace and watched as they trotted across the ruts ahead. They were does all right and evidently very interested in me for they crossed over to my left, some 500 yards away and stood there quietly, watching me as I eased along.

I had read a great deal about their inveterate curiosity and their propensity toward racing vehicles. Here was an opportunity to learn something about the habits of my quarry.

Cracking the throttle, I moved briskly through the gears. Up on the pegs, bouncing merrily over the ruts, switching tracks to dodge patches of sand and a pot hole or two, I glanced down at the speedometer to find the needle dancing around the 45 mark. A quick look toward the left showed the antelope paralleling my course, running easily about 200 yards abeam. By golly, it had worked! They had accepted the challenge! Now, if I could just find a willing buck and try the same trick on him . . .

Two-hundred yards ahead, I saw the tracks tumbled abruptly into another dry river bed. That marked the end of the race as far as I was concerned. Shutting down, I glanced over at my competitors. They were swinging away from me, running effortlessly, and by the time I reached the dry wash, had disappeared over a small hill.

For the next half mile, the road snaked through soft, treacherous sand and my front wheel started acting with a will of its own. By steering with the rear wheel — shifting weight and goosing the engine to change direction — I managed to complete this section without penalty, as the trials reports so aptly put it. Finally, I shook the last of the loose stuff off my wheels with a sigh of relief, climbed to the crest of a small ridge and stopped to let the engine cool.

I found myself looking down on a small, shallow basin roughly two miles in diameter. There, almost precisely in its center, was the main herd. There were about 40 of the little animals, grazing contentedly, ignoring the activity around them. And there was plenty of that! I could see five other hunting parties ringing the herd, all presumably facing the same quandary I was: how to get withing range of the antelope without spooking them!

The impasse was shattered by two impatient hunters on my left. They started walking toward the herd and, to my complete amazement, opened fire at something like 800 yards! Jets of dust, pluming from the basin floor a bit more than halfway between the gunners and their targets, marked the limit of their rifles' trajectories. A ripple of uncertainty fluttered through the herd. Deciding that the shooters' intentions were hostile, they wheeled about as though on signal, darted up the flat slope and dissolved in a hazy cloud of dust over the basin's rim - away from the would-be marksmen and away from me.

Down the twisting, bumpy road I went. This was pure chase now and I concentrated on the machine and the road surface. Thundering over the basin floor, I sped up the other side, then dropped my speed as I neared the rim. A splatter of shots ahead drew my attention to the right when I eased out on the flat. There, about 150 yards off the road, I saw two hunters kneeling over the prostrate body of an antelope. I parked the bike and walked over — I just had to see what one of the little beasts looked like up close.

As I neared the men, I was astonished to see. not more than 80 yards away, two antelope calmly bedded down, nonchalantly watching the hunters dress out one of their ex-relatives!

After observing the usual amenities, I jerked a thumb toward the spectators. "Does?" I inquired.

"Yeah," answered one of the hunters. "I think one of 'em's wounded. The Warden told us there was a gut-shot doe running around here and I think it's that one," he said, pointing to the nearest animal. "She sure acts funny."

I examined her through my binoculars but couldn't see any sign of a wound. Laying my rifle aside, I helped the men finish their chore but continued to eye the two does. I couldn't understand why our presence failed to excite them or how they were able to ignore the pungent odor of freshly-spilled blood.

As we finished, the nearest doe stood up. Again, I glassed her carefully, but failed to see any blood. The other antelope scrambled daintily to its feet, walked over to the doe, and to our considerable amazement, made it abundantly clear that he was anything but female!

While we discussed the proprieties of shooting at an animal at such a delicate moment, the doe lost interest in her admirer and began walking sedately away. Undaunted, the buck followed closely and both quickly disappeared behind a low knoll to our right. Bagging him now would be more of a sporting proposition, so I flipped the safety off my rifle and trotted around the other end of the mound. There they were, both of them, about 150 yards off, still walking slowly away.

I dropped prone, only to discover that the slight downward slope of the ground in front and the ever-present sage made it impossible for me to see the animals. Rising, I assumed a kneeling position and peered through the scope. The little buck was facing almost directly away from me. Since a shot from that angle would destroy a lot of edible meat, I decided to wait.

A rifle cracked behind me (I never did find out who fired or where he was) and kicked up a blossom of dust right under the buck's nose. The doe spun around and loped off to the right with the buck, ever faithful, tagging along some six feet behind. Excitedly, I swung the crosshairs ahead of him and tugged the trigger. Dust exploded at his feet! Cursing myself, I bolted another round in the chamber, swung the sight past the buck's shoulder — he was really moving now, head and neck stretched straight out — past his nose, to an imaginary spot about three feet in front and held it until I was positive my swing matched his pace. Squeezing gently, I felt the set trigger grate ever-so-slightly just before the rifle jarred against my shoulder. The sound of the report was echoed by the solid smack of the bullet striking home. He was down!

The antelope was slightly over 200 yards away when the tiny bullet caught up with him. It struck him in the neck, shattered about two inches of vertebrae and killed him instantly. He never felt a thing; it was a good, clean kill.

It took about 20 minutes to photograph him, dress him out and load him aboard the Sprint. During that time, the clouds, which had been lowering ominously, decided to unload their cargoes and a cold rain began pelting down. By the time I tied the last knot securing the animal to the saddle, it was pouring and the ground underfoot was slowly turning to grease.

It took an hour and a half to cover the three miles separating me from my truck. The extra weight behind me stiffened the ride considerably and, even though I eased along slowly in first, the constant jarring loosened the ropes and I was forced to stop several times to tighten things up. While I was at it, I scraped the accumulated mud from between wheels and fenders. It was slow going but, thanks to my cowardly approach to muddy surfaces and the inherent stability of the Sprint, I made it back without incident — feet up all the way. — Well, would you believe half the way? ■