GREEVES ANGLIAN

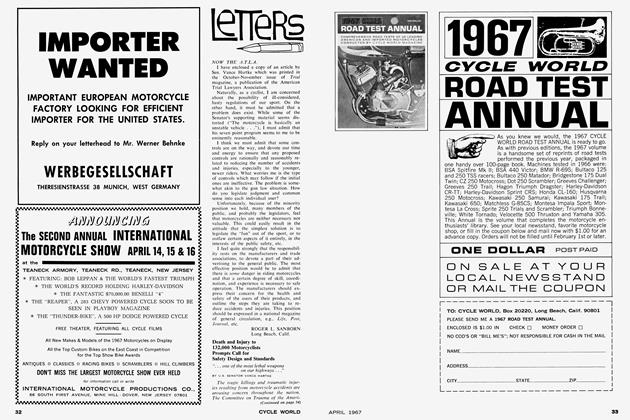

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

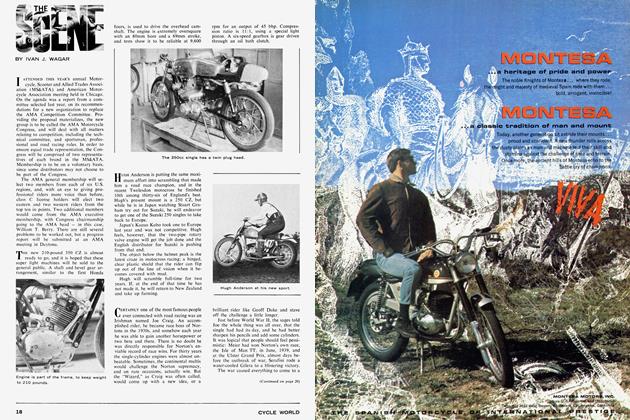

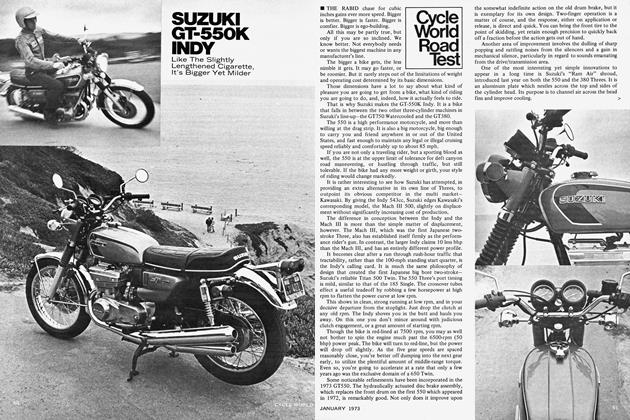

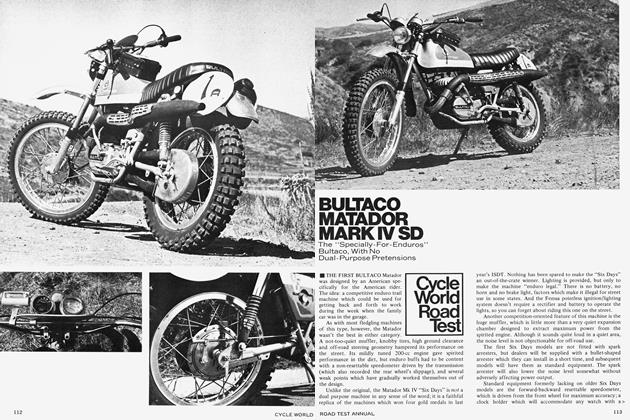

MIDST ALL THE EXCITEMENT about the recent Super-trialer autographed by you-know-who, one tends to forget that the feet-up game originated in Britain, where — by dint of many winters of experience under the most atrocious skies in the world — the natives are still producing rather devastating weaponry. The 246cc Greeves Anglian is just such a motorcycle, and in the hands of such stars as Don Smith and Mike Jackson, has kept both Scott-type and “pure” observed trials results from being a foregone conclusion.

From what the reader has seen of the CYCLE WORLD trials issue so far, he may have noticed that there is a trials bike “formula,” a tangible series of attributes and dimensions. A trialer’s superiority over another seems to be determined in part by how well the formula is executed; deviation, if any, is rarely extreme. While the Anglian follows the traditional trials layout in every respect, it has one particularly distinguishing feature — it is a great machine for the non-expert. One cannot, with great assurance, point to any single feature on the Anglian which makes it behave that vay, but perhaps one can find the combination.

At 228 pounds with gas and lighting, it is competitively light for a two-fifty, but not the lightest. The frame is a variation on the TFS Trail (tested March, 1966); the main section, in fact, is virtually identical in configuration with its distinctive “Greevesian” cast aluminum alloy downtube, welded-up box section cradle, and rearward arcing maintube. The rear section, however, is higher to accommodate a full-sized 19-inch wheel and tire; it also extends farther back to give the 12-inch constant rate Girling spring-damper units a near-vertical attitude and the accompanying mechanical advantage this position offers for optimum damping. Judging by the tube sizes, this frame shows no signs of being intended for any less abuse than either the trail bike or the scrambler.

The steeply raked forks are of the new design introduced last year on the Challenger, incorporating external spring-damper units and offering a generous 6V2 inches of travel. Accordingly, the front suspension does a good job of leveling rough terrain; it is firm without jarring and as such is probably an important factor in preventing fatigue in the rider’s forearms and wrists. The front end, probably because of the leading link design and the extra inertia it produces, does not have the precise feel that a telescopic fork produces, but it is more than up to the job, and is particularly attractive when one considers how much less expensive it is.

Use of the 21-inch front wheel is absolutely necessary, of course, as this is the single other most important factor in determining how precisely a dirt machine follows the helm. Greeve’s choice of the full-size 19-inch wheel in the rear explains, at least in part, the secret of the Anglian’s excellent grip on a wide variety of surfaces; the rear wheel had virtually no tendency to crab downhill on moderate off cambers or dig itself a hole on steep, dry climbs.

The Anglian is one of the last Greeves models to still utilize a Villiers lower half instead of the beefier allGreeves engine one finds in the MX3 series. This is quite natural, as the Villiers 37A unit used on the trialer has no need of sustaining the high output of a scrambler engine. Greeves, however, adds to this a special light-alloy “square” barrel and head with generous finning and a geometric compression ratio of 11:1. While the ratio may seem high for slow and steady going, such is not the case. The engine is an easy and almost immediate starter, cold or hot, and only seems to gain from the high pressure in terms of low and medium speed torque. The Anglian is extremely difficult to bog down in low cog, as it will either lose traction or gently raise its front wheel before continuing on its way — which is either upside down or forwards, depending on the rider.

An added benefit of the high compression ratio is that it takes the gritted teeth out of most downhill descents; the engine simply refuses to be hurried down and the pilot is not so tempted to use the back brake and risk killing the engine or setting things to sliding.

Slow running, important in trials, is excellent, although we did manage to stall out once or twice by getting overconfident. We also found that the engine requires a practice common to two-strokes — cleaning out the engine during extended, slow downhill sequences by blipping the throttle, this to ensure instant and precise throttle responsewhen it is needed at the bottom of the grade, or to turn out. The Anglian boasts one of the new Amal concentric carbs, which probably does much to enhance slow running, and minimize this problem.

The manner in which seat, pegs, handlebars and controls are positioned follows the trials formula quite nicely. The handlebars, for instance, are wide and flat; they measure 31.25 inches across and we would be willing to bet that the reader couldn’t find more than about an inch variation, were he to run around madly measuring trialer handlebar widths. Ground clearance is fairly decent at nine inches. The foot pegs are 13 inches from the ground and rear set, of course; little beads have been welded onto their tops to provide a “gripping” surface, which may prove useful in the mud, if not in dry weather.

In seated or standing position, rear brake application requires no shifting of the left foot. Shifting from one gear to a higher one, however, does require one to move the right foot off the peg, unless he is blessed with size 13s. But as the Villiers shift pattern is one-up-three-down, and situations in which one is accelerating through the gears are not so demanding as downshift situations, moving one’s foot is not so difficult. Ah yes, but what about downshifts, you say? Fortunately, Greeves saves the day with a rocker type gear lever, the rear tang of which falls right to foot when the rider is in standing position; shifting from a higher gear to a lower one, then, also involves only a downward stab, rather than an uncomfortable upward pull.

Nowadays, a new school on trials gear ratios holds that the first three ratios should be close together and then have a wide jump to fourth. The Anglian remains with the old school, prescribing a bigger jump between second and third. In practice, the difference is not that noticeable, and the Anglian still offers that charming and necessary trialer habit of gobbling up three gears very quickly on the flat and then dropping from a soprano whine to a baritone fog in the change from third to fourth. Fortunately, the Greeves-Villiers unit has the torque to handle this change of register gracefully, even on an upgrade, so one gradually arrives at midrange in this highway overdrive, buzzing along at 40 mph and up, relaxing a bit and maybe even thinking about the next section to conquer.

One cannot fail to remark that this is a very comely little machine; much of its beauty is in that slim, bright red fiberglass two-gallon fuel tank. The tank’s slimness is also functional; it measures only VÁ inches wide at the back, which not coincidentally, is the same width as the front part of the trials seat. Midway, the tank is still only six inches wide, offering a narrow, comfortable profile for the knees to grip in standing position. The tank, held on by two elastics, is easily removable.

Finish is good, and even the functional parts such as the aluminum fenders, high-folding kickstand, and slotted number plate, are attractively done. The welds are clean and strong and the painting on frame and suspension units looks faultless. Aircraft locking nuts have been used throughout.

All in all, the Anglian is a fine example of a fine breed, and in being good for the duffer, it must also prove a useful tool for the expert.

GREEVES

ANGLIAN

$830