all about SIDECAR RACING

A Serious Primer On The Three-Wheeled Art

JOSEPH BLOGGS

Although non-English crews and BMW rigs have dominated the international championships for many a year, it must be conceded that Great Britain is the world Mecca of sidecar road racing, particularly in classes larger than the international 500cc formula. The author, a native of the London suburbs and one of England's leading motorcycling freelancers, gives us an intimate and technical look at the "left hand" version of the sport as practiced today.

S IDECAR RACING has been, until recently, an exclusively European and British sport. Its development in the USA has been hampered, in part, by lack of data on the machines and technique used by overseas crews. Once this exciting sport catches on in the States, however, it should grow rapidly.

The late Ted Hampshire, one-time service manager at Vincent-HRD, described the sidecar as "an unmechanical device," probably because such a rig is asymmetrical in just about every way. This must never be forgotten. Power application is one-sided. The center of gravity does not lie on the center line of the outfit, but instead is nearer to the engine. Only one wheel steers and that is not central. Further, the brakes are usually (but not always) applied on only one side of the combination. Even if the chair wheel is braked, the distribution is still biased in favor of the machine. Consequently, a racing outfit — like a touring model — crabs towards the chair side when the power is on and away from it during braking. When the engine is on the float, neither pulling nor braking, the outfit steers straight of its own accord. This is the only time when the steering wheel, the front one, is not deliberately turned slightly one way or the other to combat either wheel traction or the brakes.

The neutral conditions are almost never obtained in road racing. It does appear briefly on the 37-3/4-mile Isle of Man circuit, to which sidecar racing first came in 1923. It is probably 100 percent correct to say the neutral state never appears on a short circuit or even a typical Continental GP circuit like that used for the Dutch TT at Assen. But the neutral condition is very common in road work and the geometry of the outfit must be tailored to account for it. Light throttle usage in traffic or speed limits produce close and lengthy approximations to the neutral condition.

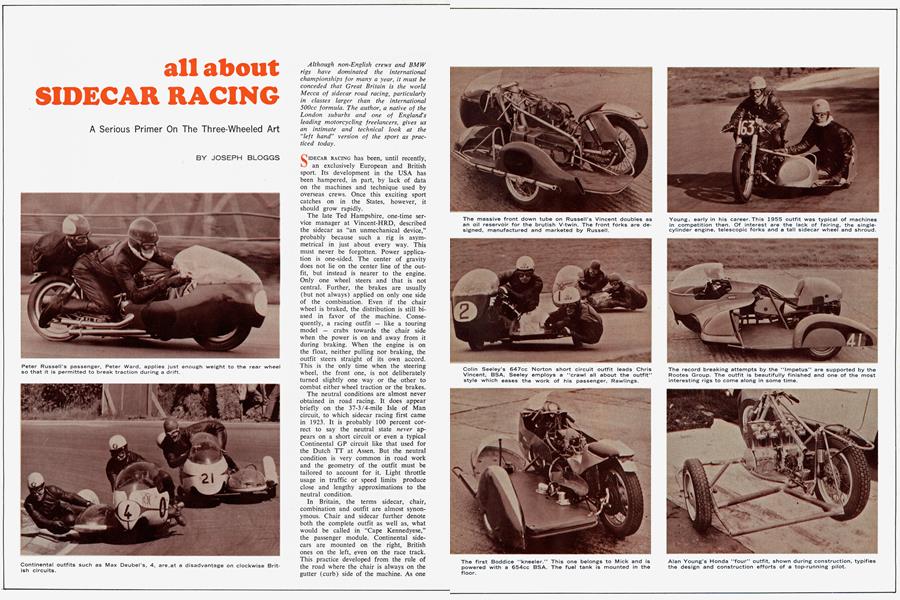

In Britain, the terms sidecar, chair, combination and outfit are almost synonymous. Chair and sidecar further denote both the complete outfit as well as, what would be called in "Cape Kennedyese," the passenger module. Continental sidecars are mounted on the right, British ones on the left, even on the race track. This practice developed from the rule of the road where the chair is always on the gutter (curb) side of the machine. As one corners better away from the chair, a Continental-trimmed outfit (i.e., chair on right) is favored by a counter-clockwise circuit. A British chair — which seems most likely to be adopted in the USA — is at a definite advantage on a clockwise circuit, because it corners better to the right than the left because it drifts more easily in this direction. This advantage is particularly apparent when the few cyclecars or three-wheelers in use on British tracks mix it with outfits. A good three-wheeler like Owen Greenwood's Mini-Special has an advantage over a British outfit, by a significant margin, on lefthanders. But on righthanders, the top sidecars are fractionally faster. We shall consider, to avoid tedious qualification, that a British outfit, with the chair on the left, is in mind.

A good racing outfit must lose rearwheel traction to handle well on either sort of bend. This is why tires of only 3.25-inch section are sometimes used when 3.50-inch rears are normal to an equivalent solo. Centrifugal force, throwing the weight to the outside of the bend, allows the rear wheel to spin much more on righthanders than it does on lefts. The speed differential between the two corners is of the order of 10 mph at 70 mph. An outfit set up so that traction cannot be broken is almost unraceable, however well the owner may think it handles in any private sallies onto a test circuit.

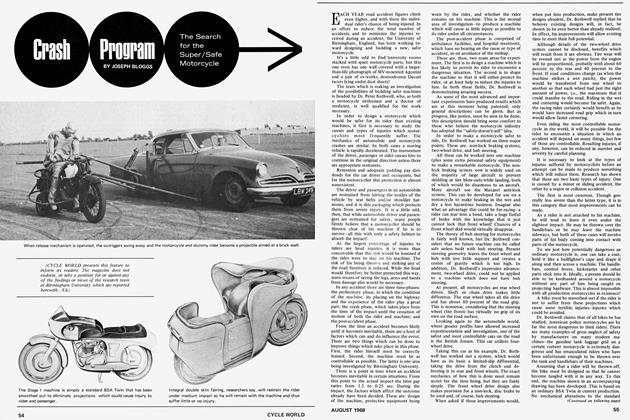

British racing outfits weigh about 400 pounds dry with streamlining. They fall broadly into two classes: those with integral side car chassis and machine frame and those in which the sidecar is attached or bolted to the bike. To the latter school belongs Bill Boddice, veteran sidecar racer now succeeded by his 18-year-old son, Mick. "I believe in racing only genuine sidecars," says Boddice. "My test is this: The sidecar should be detachable so that the machine can then be wheeled away and ridden." Of course, the riding of such a specialized "solo" would be barely classable as riding, but Bill makes his point in unmistakable Boddice manner, typical of the Birmingham background to which he belongs.

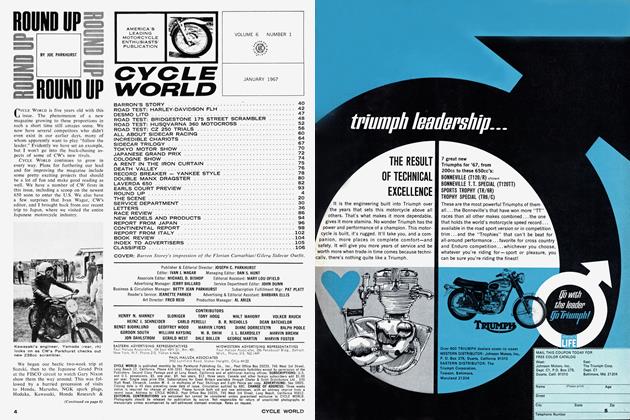

The other view is taken by Colin Seeley, of South London. Creator of the Seeley specials and sponsor of Derek Minier earlier this season, Colin believes in welding the machine and sidecar chassis into one. Indeed, they are one, for the bike has no frame of recognizably solo origins.

It used to be general practice, up to about a decade ago, to attach chair to bike by two ball joints low down and two or sometimes three plain bolted attachments at top rail height. The ball joints were like automobile tie rod ends, carefully set to permit some movement of the ball in the cup, like a human elbow or knee. It was found that if they were screwed up solid, they broke. No one ever found out or much cared whether the ball joints were needed to cope with flexing of flimsy chassis and frames, or because the neck of the ball was too weak. The arrival of full plain-bolting stopped such inquisitiveness.

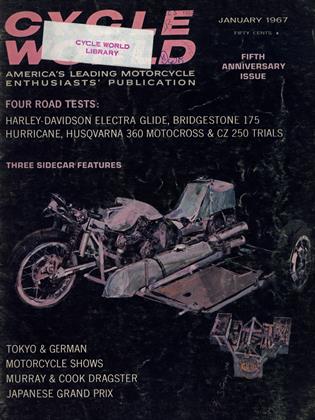

The usual practice these days is to bolt the chair and bike together solid. If 5/16inch bolts break, the builders increase the size to 3/8-inch, and so on. A typical integral layout consists of a machine "frame," which is more or less recognizably Featherbed. Londoner Alan Young, who has spent three years creating a 500cc Honda four-cylinder outfit by "nailing" a pair of 250s together, has had to use a special frame, as his outfit is crab-tracked. The machine wheels are not in line, the front wheel running half-a-tire's width outside the rear wheel. This is no handicap, by the way. Alan optsfor a simple rectangle for the sidecar chassis, but most builders make it triangular with the chair wheel at the apex. Welded-on loops, extend forward and rearward to mount the platform. Young has used aircraft-quality T80 and T90 tubing, some as light as 21 gauge. More common is T45 and T50, of lower tensile strength but cheaper and more readily available. Peter Russell, of Northamptonshire, a successful driver of a 998cc Vincent outfit, uses 18 gauge T45. The front downtube is of four-inch diameter and the outfit weighs 416 pounds.

Another constructor working in nickelbronze welded T45 is Ian Johnson of Nottingham. His 650cc Johnsonian has a Triumph engine with a 180-degree crank and uses, like Russell, the 4-inch downtube. But the rest of the outfit is in 16 gauge T45, of either 1-1/8 or 1-1/4-inch diameter as appropriate.

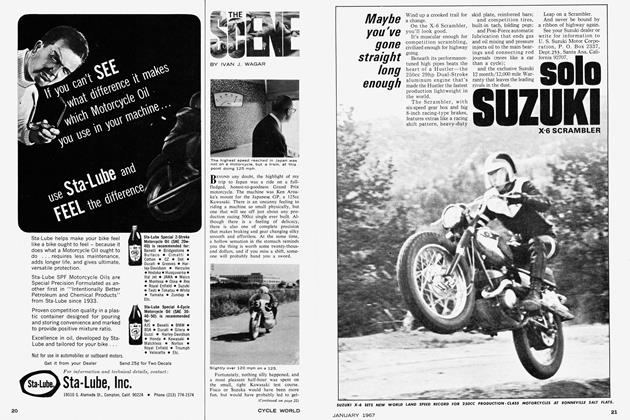

One of the prettiest outfits to appear this season is the Impetus, built by two South London men, using a 998cc Imp engine, supported officially by Rootes, the Hillman car company. The frame and chassis are integral in 1-1/4-inch diameter 17g T45. Weight is 400 pounds. Two adherents to Reynolds 531, which can be fusion-welded, are Colin Seeley and Bill Boddice. Bill and his son, Mick, build their own outfits, and their latest one, using a semi-factory 645cc BSA A65 motor, has the usual Boddice bolt-on chair of 1-1/4-inch diameter x 16g. Like the Impetus, Mick's latest weighs 400 pounds.

Steering head angle usually approximates to 65 degrees though Young goes for 69 degrees. Boddice has 64 and Seeley 63, but it is probable that the 63 to 65 value is close enough and the difference may be due to measuring inaccuracies anyway. Young's steep steering head angle is definitely a departure from general practice. Head angle of a standard Manx Norton is 64-1/2 degrees though the factory does not claim to make them more precisely than plus or minus one degree.

Much more critical is trail. Ten years ago, telescopic forks were general. Trail was excessive and tire squeal the regular thing. Today, few people have telescopies — Seeley was one of the last, with a very successful Matchless G50 outfit — and tire squeal is no longer a part of the atmosphere of a meeting. If an outfit screams its front tire, its handling is wrong because of too much trail. Usual figures, compared with the four-inch trail of a 500cc solo, are 1/4 to 3/4-inch (measured at half stroke), though Eric Oliver — who retired in 1955, followed by a brief compositive back — has used 1/4-inch negative trail. The handling is then without feel and only a great deal of experience will keep it "between the hedges."

At zero trail, which several people have, there is a sensation of driving on ice. Again a very delicate touch is required. The Impetus has 1/2-inch trail, the same as Russell's big Vincent. Boddice uses 1 inch, while Seeley recommends 1/4 to 1/2 inch and no more for the competent driver. Young uses 1/4 inch. A novice is well advised to start with 1-1/4 inches to get the feel of things. There will be some shoulder ache which will disappear as he works his way down to less trail.

Leading-link forks, either genuine Reynolds or copies, are usually made with eccentric pivot spindles to permit trail adjustment unless, like Seeley, the builder is sure enough of himself to set them up at one fixed value. Front fork movement is generally about two inches but less with teles and typical spring poundage is 100. The rear legs have about 3-1/4 inches of travel. Honda or Girling telescopic steering dampers are used to combat handlebar flutter on bumps.

Seeley makes his leading-link forks from 531 tube. The stanchions are 16 gauge about 2-inch diameter and the arms, also of 531, are 1-1 /4-inch-diameter and of 10 or 12 gauge. (Material availability often determines sizes and gauges.) Joints are nickel-bronze welded.

Norton rear swing arms are common, generally lengthened and strengthened. Phil Irving has increased lap speeds of Australian Vincent outfits by several miles per hour solely by moving the rear wheel back two inches in the stock Vincent rear fork.

In Britain, the longer-than-solo wheelbase is 57 to 58 inches, though Russell's outfit, which tends to suffer from frontwheel patter on leaving righthanders, has only a 56-inch base. A Boddice outfit drifts well with only 54 inches.

There is no general agreement on track. The narrower the track, the livelier the outfit. Seeley puts the minimum at 32 inches and used 36 inches on his last Norton 650SS outfit. Russell has 33, Boddice 36, while Vic Phillips' Impetus has 40, definitely on the wide side. Weight carried by the sidecar wheel (unladen), is on the order of 75 pounds.

Lead, the amount the chair spindle leads the rear wheel spindle, averages 10 to 12 inches. Some outfits have had as much as 18 inches — used in the Garrard racing sidecar — but this is too much. The more lead, the greater adhesion of the rear wheel, which may be an asset on righthanders, depending on tire section and engine torque, but is a handicap on lefthanders unless the chair wheel is intentionally aviated. Two retired riders who were pastmasters at this were Eric Oliver and Vincent factory rider Ted Davies. Modern geometry and perhaps tires have produced outfits which handle well on lefthanders with the tire still kissing the tarmac.

Drifting is certainly influenced by the surface. Most British tracks have coldrolled asphalt with coefficients of friction better than 0.8 dry and 0.65 wet. Concrete is rare. Airfield circuits are now few and generally resurfaced on bends anyway. No drifting sets in much below 35 mph. To court a deliberate breakaway at low speeds is to invite upending the outfit.

It is usual to make the sidecar wheel toe in, an absolutely essential factor for a road outfit which needs 1-1/4 to 2-inch toe-in. But race versions have less, rarely more than 3/8-inch. Russell has none, while Seeley goes for 3/8-inch toe-out. The matter isn't critical and mainly determines how much brute force the driver will have to exert to lock the front wheel over enough to keep the rig straight under full power.

The amount of weight carried on the front wheel is also a factor here. Too little will allow the wheel to patter on righthanders — a fault with Russell's outfit — whereas too much may allow the back wheel to spin so readily that power cannot be used freely on corners.

All Boddice outfits, with a forward disposition of weight, are renowned for their excellent driftability, the back often hanging out until 30 degrees of lock is in use. However, they do generate wheelspin rather easily.

With a road outfit, the machine is made to lean away from the sidecar. This lean-out is measured at the steering head by dropping a plumb line to the ground. The difference, at ground level, between that line and a projection of the steering head axis is lean-out. A road outfit requires 1-1/2 inches unladen to combat road camber. On flat roads, zero lean-out is permissible. Lean-in causes the wheel to lock over and requires the shoulder muscles to fight the caster effect all the time the power is on. In road racing, a vertical setting is not uncommon. The Impetus is so set, with the machine laden with crew. Seeley likes about 1/2 inch lean-out. Boddice keeps his vertical when laden and tilts the sidecar wheel over at the top, towards the machine by five degrees. Young tilts the chair wheel out slightly, believing this reduces the tendency of the tire to squash under the rim on righthanders; he also has a trace of lean-out at the head.

Sidecar wheels are almost always 12 inches, with 16-inch ones on the machine. This practice is partly dictated by the availability of flat-tread uni-directional sidecar racing tires in those sizes. Noncling (low-hysteresis) rubber is preferred, as too much grip in the dry from cling rubber makes drifting a little harder. Of course, this produces rather hairy sliding in the wet. No one uses high-hysteresis covers specially for the wet because it is difficult to change wheels quickly on a motorcycle, in contrast to car practice.

(Continued on page 84)

Seeley opts for 3.50 front and 4.00 rear covers, this being typical. But Boddice has 3.25 on both wheels to encourage breakaway. Sidecar wheels are always of 3.50 section. The eight-inch sidecar wheel has been used, from a scooter, but is not quite as good as the 12-inch. Larger ones, of 16 or even 19-inch rim diameter were once fashionable but give a tall wheel cover which creates drag. Too small a wheel creates a braking problem. A third stopper is almost never used on short circuits, where the race distance rarely exceeds 20 miles, owing to high mechanical mortality and the consequent loss of spectator interest. But in GPs of 70 miles and more the machine brakes hit fade and the addition of a sidecar wheel brake is rated an asset. Machine brakes are enormous. Drum brakes have gone as big as duo nine-inch, both sides having two leading shoes. A few people struggle along with a standard Manx front anchor. For the rear, a G50/7R or Manx brake is considered adequate. The more-efficient disc brake is gaining favor and is being seen in increasing numbers.

Unlike solos, full streamlining (dustbins, garbage, trash cans) are permissible in F.I.M. sidecar racing, but they create cooling problems. A duct to the front brake and several to the engine are normal, and four-inch-diameter car ducting is generally used because it is flexible and cheap.

Engines get a bigger beating than in solo racing and ample flywheel effect is essential if breakaway at the rear is not to be marred by either the tire biting between power impulses or an embarrassing rev rise.

Piston trouble is common, doubtless aggravated by the weak mixture often appearing during cornering in one direction (caused by centrifugal force). The 650cc Johnsonian has Weber carburetors which are more or less invulnerable to fuel swill, or sideways surging. Other outfits are fitted with swill pots. These supplementary floatless float chambers on the opposite side of the mixing chamber help eliminate swill with Amal Monobloc and GP carburetors.

SU float chambers are common. So, too, is a pump-fed system with either lowpressure feed to the carburetors or a header tank and line returning the surplus to the main tank, carried on the sidecar floor alongside the clutch. Most tanks hold 3 to 3-1/3 U.S. gallons. On kneelers, pump feeding is, of course, essential, as the rider's chest is on top of the mixing chambers.

Very few G50s or Manx Nortons are still sidecar raced, nor are Gold Stars. Most people in England have 654 BSAs or 649 Triumphs and a few 647 Nortons. Engine capacity is limited to l,300cc. The few BMWs remaining — which are used as little as possible to conserve "unobtainable" spares — are essentially GP machines and are fitted with swill pots and often Dellortos. Injection has almost disappeared, even on BMWs.

The engine should be, but all too rarely is, tuned for reliability rather than sheer power. Ten-to-one compression ratio is plenty. Coil ignition is almost universal, from a six-volt motorcycle battery carried in the sidecar nose. It can also power the SU or Bendix low-pressure fuel pump, but people have driven these quite successfully by a swash plate or cam and rocker from the sidecar wheel.

Kneeling is now very common. This design creates push-starting difficulties — all non-GP events are dead-engine ones when the flag falls — but gives a lower center of gravity and hence better cornering, as well as less frontal area. Gearchanging in a corner is easier with a kneeler. The brake pedal is attached directly to the brake cam and the matching gear pedal works via a long shifter linkage to the inevitable Manx box. Machines are geared for about 105 to 115 mph for the average short circuit, though 120 mph can be reached on, say, the long course at Silverstone or 130 mph in the Isle of Man. Lap speeds are almost identical with those of British 250cc solos. Typical 650 Norton cogging might be 21-tooth engine sprocket, 42-tooth clutch sprocket, 19-tooth gearbox and 54-tooth rear wheel, to give a 4.7 top-gear ratio. Standard 1, 1.1, 1.33 and 1.77 Manx internal ratios are customary. Five-speed boxes are unnecessary. The clutch should have an extra plate and maybe stronger springs, too.

Rear chain life is short, and tires last only 100 miles or so, though the front tire may, and the sidecar tire will, better this mileage. The abrasiveness of a circuit has a very marked effect on rear tire wear. Most British tracks are now, as mentioned previously, surfaced with a cold-rolled asphalt, at least on the corners. The few remaining airfield circuits have a low coefficient of friction and abrade tires faster. All tracks are hard-surfaced throughout their lap; there are no mixed dirt and pavement surfaces.

Cycle cars or three-wheelers are permissible, providing they meet certain regulations. Owen Greenwood's l,071cc MiniCooper unit is currently dusting off all but the very top aces. Other three-wheelers like the Mogvin (998 Vincent) and Skitsu (650 Triumph) have enjoyed only small success, rarely finishing in the money. There is talk of banning Greenwood's semi-car. It is not only faster than all but the very best chairs, but laps a short circuit quicker than a Mini-Cooper car.

CREWING

At any British meeting, when the chairs come to the line the crowd comes to the ropes. Sidecar racing is rated a spectacle superior to all but the closest-fought solo race and much better than car events. From a dead-engine start, five or more outfits abreast on the track in as many ranks on the grid as may be needed, the field departs at the signal from a flagman. Both crew members push. Co-ordination is necessary; if a passenger is not quick to leap aboard, the outfit must crash at the first lefthander, for the driver can be unaware that his passenger is missing until that first bend.

A good start is essential, as passing is harder than with a solo. The field rapidly sorts itself out, because there is a marked disparity between the performance of the leaders and the also-rans, more obviously so than in solo racing.

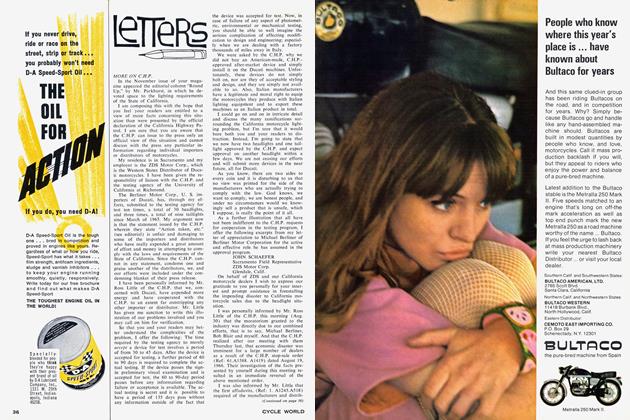

With grab handles fitted to taste, and the rear wheel, chain and clutch shielded, the passenger can hang well out behind the driver on righthanders. On some very fast bends, he may be content to crouch and merely look around the driver's posterior so that rear wheel traction can continue to be broken. No signals are given and in the event of a filler cap coming loose or even a carburetor all but falling off, the passenger is expected to act without instructions. On the straights he lies flat and makes himself offer minimal wind resistance. His slipper-shod toes practically touch the ground where his lower legs hang beyond the padded passenger pan. Looking through either a perspex nose or a glazed window cut in the metal or fiberglass streamlining, he judges when to take action stations again. He leaves this until the last moment and then moves gently but purposefully, so that his movement cannot be felt by the driver.

On lefthanders, he will extend himself only as far as he knows to be necessary for stability, as a fully-stretched out passenger creates considerable wind resistance. A team may be able to take a 100 mph moderate lefthander with the crewman fully lying down in the straight-ahead position. The chair wheel may then rise off the ground as much as half its diameter, say six to eight inches. The contrast between the aces and the also-rans when this happens is marked. The tailenders' passengers hang out for all they're worth. On a maximum-effort lefthander, a crewman's elbow and shoulder may touch the ground, and most crewmen have tattered leathers as proof of this.

In the wet, he will dispose his weight to aid adhesion. Some rapport will develop between a good crew so that, in traffic, when overtaking slower outfits, the passenger will intuitively know where to place himself without advice from the driver as to which side he proposes to dodge to complete the passing maneuver.

In the event of a crash, the passenger will endeavor to remain with the outfit as long as possible, because an empty chair is almost impossible to control.

DRIVING

The engine should fire instantly. The clutch gets a violent slipping, if a good start is to be obtained. In live-engine GP starts, which seem to be getting more common in smaller races, the sight of a burnt-out clutch is not unusual. Bottom gear will be used for the only time in the race. If no corner is slower than 45 mph, second gear may also have only one spell of usefulness; marked wheelspin in third will keep the outfit drifting and replace second, which would be used on a solo for the same bend at comparable speed.

At the end of a straight, the brakes must be used skillfully, the driver being aware that the passenger is now about to complete a handholdless transfer of position. Marked slewing to the right occurs as the brakes go on, with a large overcorrection if they have to be prematurely released. Very late braking, with some speed being scrubbed off by the tires being slightly sideways, will occur on the approach to a righthander, but no scrubbing-off will occur on a lefthander. In both cases, power will be restored before the apex of the bend so as to keep traction broken. On a lefthander, lots more power will be poured on earlier to keep the machine driving 'round the third wheel. If a gearchange unfortunately intervenes, as it does at Silverstone and at Brands Hatch, the outfit will snake or twitch as the cog is swapped.

On righthanders, only a little power will be applied almost up to the apex of the corner, just sufficient to keep the rear wheel turning faster than the front. With the handlebars set to slight lock, and hardly altered intentionally from that same maintained degree of lock, the power is screwed on to the maximum that is permitted by the front wheel stepping sideways and the outfit coming too close to the outside edge of the track. It is usual to clip the verge. If the throttle is eased back, the turn tightens. As soon as the apex is past, maximum acceleration is then sought.

The driver ignores the passenger, relying on him to be in the right place at the right time. A signal will be given when pulling to the edge of the track at the end of the race or when broken down, and the passenger will usually make this, with his left arm, on his own initiative.

Camaraderie amongst sidecar men is intense, much more evident than with the soloists. The large amount of mechanical trouble, the team work and the feeling that it is a battle against the machine rather than each other, probably accounts for this.

In England, handicap races usually follow the scratch (all-start-together) ones, the timekeeper basing his assessment on the scratch-race performances. In an important meeting, where the handicap prize money is definitely worth having, "foxing" (the British equivalent of "sandbagging") is normal early in the day.

After a meeting, sidecar crews and their families tend to get together in impromptu brew-ups of tea, together with the inevitable sausage-and-beans in each other's vans. Most have a converted bus or furniture van, because of the size of an outfit. Greenwood favors a homemade copy of a glider-carrier for his Mini-Special. Boddice has a single-decker bus fitted by his typical ingenuity with every device for comfort. Others who are able to split bike from sidecar put the former in the body of a shooting brake (station wagon, pickup) and the latter on the roof. It is not unusual to see a pair of outfits carried in this way on the one vehicle.

With the exception of the late Florian Camathias, whose forks broke at the brazing, permitting a fatal accident, sidecar racing has proved to be remarkably safe. Its hairy and often frightening cornering, the close company which the speeding outfits keep, and the spectacle of crewmen hanging out for all they're worth, have elevated chair events to the premier viewing position in any program. Not only is a solo-only meet a rarity in Britain, but sidecar racing has progressed to the point at which a paying promotion can be staged without any solos at all, Mallory Park being the first venue to put on an exclusively sidecar speed spectacle. ■