CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

It's what's up front that counts.

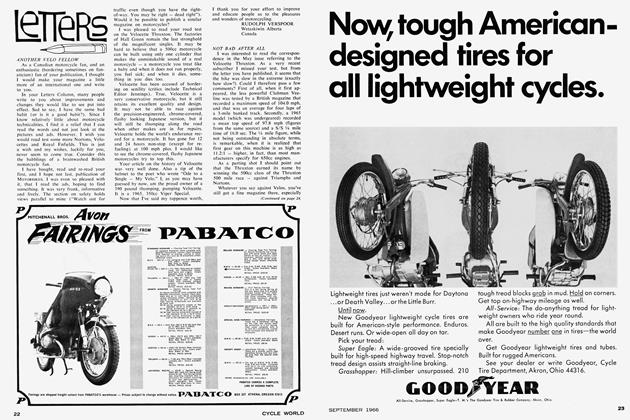

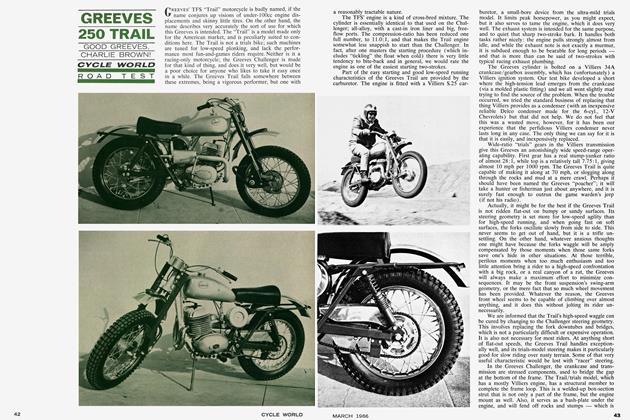

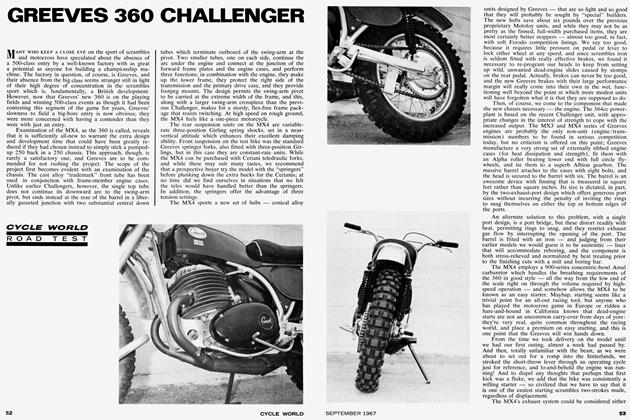

THIS YEAR'S GREEVES 250cc-class scrambler may not seem to be new. Admittedly, the big transition came in late 1964 when the first Challenger was introduced with a potent all-Greeves engine instead of the previously used Villiers. But looks are deceiving and the changes are subtle. As the saying goes, "it's what's up front that counts," and in that department alone, Greeves has enough new items to rate coverage. With other small but important improvements, the 1966 Challenger (color it blue and label it MX3B) emerges from scrutiny as a very new machine, indeed.

Any of our readers who visited the Isle of Man for the 1965 International Six-Days Trial probably saw the prototypes of the MX3B being ridden by British Trophy Team members, Bryan and Triss Sharp. Also attending those fog-shrouded and mud-clogged festivities was U.S. Greeves distributor Nick Nicholson, who examined the trophy team machine and suggested to the factory that several features incorporated in its design would be welcomed in Challenger models for the stateside market.

Greeves complied, and the big news comes in two departments — improved front forks and extended wheelbase, both of which add up to better handling.

Few would argue that the leading link forks of earlier design did a good job of smoothing rough ground. Considering their cost, they were marvels in the dirt and it is no wonder that Greeves has become the byword of many a small-bore rough rider.

In the past few years, however, that front end had also acquired another sort of reputation — one that was spoken about in the lowered tones people normally reserve for talking about others who have bad breath. "It waggles," they'd whisper. And it did, mostly on smooth surfaces at high speeds. Greeves wasn't going to take this sort of gossip lying down, and set out to do something about it.

In the resulting fork and damping unit combination, waggle has been eliminated and the effective wheel travel is 6 1/2 inches, which, it should be noted, equals the travel achieved by special scrambles forks costing nearly $200. For all practical purposes, this is more travel than can be rung out of the average production telescopic fork, under modification, by even the most resourceful of mechanics.

The aforementioned trick has been turned by a design which cannot be called radical — unless one is speaking of the clever way that it utilizes simple assembly techniques and parts already in existence.

One reason leading link forks are less expensive to produce than telescopies is that no close-tolerance machining is necessary to make plungers and the like function properly. This simplicity continues in the new Challenger design. The reader will remember that the old-style fork carried the shock absorber units inside the legs, while the pivot points for the leading link were through two plates attached to each leg. In the new version, shock units are externally mounted (and therefore can be much larger). The fork down-tubes bend backwards at their lower ends and the link length between pivot point and lower shock mounting is even longer than in the old design. Mounted immediately forward and roughly parallel to the forks is a pair of full-size Girling damper units, such as one would expect to find on the rear of a machine. These units are fitted with yellow-blue-yellow code (145-pound) springs. The possibilities inherent in having three-way adjustable fork tension are pleasant to contemplate.

GREEVES 250 CHALLENGER

There are those who will eye the five-inch compression-stroke travel of these units from static position and wrongfully deduce that fork travel could not be 6 1/2". Quite wrong, for the front wheel spindle is mounted on the leading link forward of the damper units. As the spindle is farther away from pivot than the suspension units are, its effective travel is greater than the distance over which the units compress. Add to that the decompression possible from the static position. It adds up to one, big bundle of travel and anybody who has ever slammed into a ledge or a boulder at 70 mph knows why it's needed.

Now to the other department — extended wheelbase — which was done in the interests of refining the bike's high-speed stability in a straight line over the boonies. After one has decided on what sort of rake to give the forks, there are two ways of extending wheelbase: either lengthen the swing arms or lengthen the frame. If Greeves had extended the swing arms, they would have shifted the balance of the machine too far forward; by lengthening the frame they have preserved the desirable slightly rearward weight bias (52 percent rear, 48 forward) and increased wheelbase to 54.25 inches — almost three inches more.

One may, at this point, theorize endlessly on the advantages of the new forks and longer frame. Point is, they work better. The leading link just seems to disappear like a genie into itself over small boulders, two-foot hummocks or heavily ridged and rippling trails, while rider and machine continue forward in relatively undisturbed fashion. On the fast dirt, regardless of whether it is graded smooth, undulating, flat or rippled with chattermarks, the front end remains steady. The feeling is exquisite.

The Challenger's engine is roughly the same as last year's, based on the hefty aluminum alloy crankcase, which is used as part of the frame, and an Alpha lowerend assembly with full-circle flywheels. Crankcase, and alloy head and barrel are Greeves' own. The barrel is lined with a cast-in sleeve of austenitic-iron, which matches the alloy's expansion rate closely and therefore avoids distortion. Compression ratio has been raised to 11:1. Ignition is provided by a small Stefa magneto.

Greeves is still using the Albion transmission, but this year's unit is redesigned, resulting from the ISDT workout. First gear is considerably lower, and thus more useful when one has to stop on a steep slope and then get underway again. The external arrangement of the gearbox is better; the shift lever has been moved forward of the kick starter and is now shorter, lighter and less prone to shake out of gear under heavy pounding. There is now an air-gap between the crankcase and transmission that will mean much better cooling.

The slight increase in curb weight of the model may be accounted for by two changes; one which we like and another on which we failed to agree among ourselves.

We liked the larger three-gallon ISDT-style gas tank. Desert riders who found the old 2.4-gallon job just a wee bit slim for long loops will appreciate the increased capacity of the tank.

A much more personal thing was replacement of the fiberglass front fender and rear shell (on which one easily daubed side-view racing numbers), of which some of us have fond memory and others not so fond. Nicholson's only explanation was that the "riders like the metal ones better." Some fiberglass remains, however, to shield the air filter.

One department in which the British and Europeans have been shy is the seats they put on their rough-terrain machines. Perhaps we Americans are sloppy and soft, and should try standing up more when we ride scrambles. On the other hand, maybe the British have no conception of what it is to stand up for an entire 175-mile hare-andhound in 90-degree temperatures. With Greeves' latest effort to cushion the Yankee duff, there are signs that the company is waking up to stateside needs. The seat is bigger, thicker, roomier and gives a better ride than previous ones. This is not to say our friends across the sea have yet reached perfection, but perhaps, if they stare long and hard enough at the plush American-made desert racing seat sent to them by Nicholson for study, they will get the idea.

It is very easy to carp at minor deficiencies in what is otherwise a superior machine. The Challenger is better each year because of its continual refinement. Success in the field may be attributed to the company's attention to detail and to the rider's needs (such as 45-degree folding pegs and spring steel handlebars that refuse to take a permanent bend).

The total machine — powerful, and better handling than before — is one of the finest lightweights ever to have graced the American rough.

GREEVES 250 CHALLENGER

$920