DARE-DEVILS ON THE DESERT

J. L. BEARDSLEY

TODAY we have "scrambles" and "trials" and "hare-and-hound." Yet, back in the motorcycle's infancy they had the same thing - only these were called "races."

Bucking some 400 miles of burning desert and mountains trying to be first into Phoenix, Arizona, from either San Diego, California; El Paso, Texas; or Springerville, Arizona, held far more hazards in 1913 than it does today — like trigger-happy Mexican bandits, renegade Indians on the prowl, or starvation.

These were no local clambakes for amateurs, but prize events for which racing departments of the manufacturers went gunning with some of their ace professionals. And there were plenty of hardy throttle-twisters interested in the purse money to gamble with sand, rock slides, dry washes, sun-stroke, wrecks, or being shot, to fill the entry list each year.

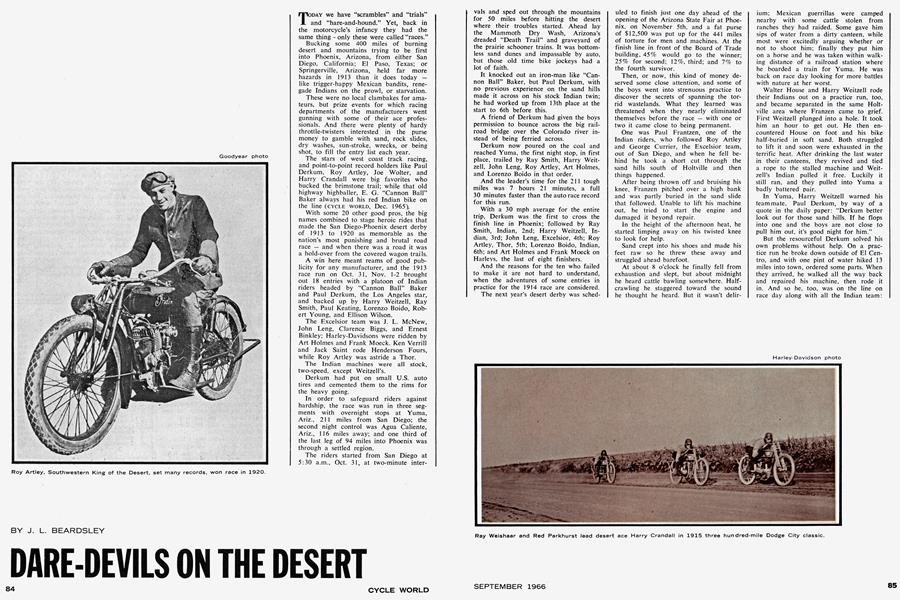

The stars of west coast track racing, and point-to-point record holders like Paul Derkum, Roy Artley, Joe Wolter, and Harry Crandall were big favorites who bucked the brimstone trail; while that old highway highballer, E. G. "Cannon Ball" Baker always had his red Indian bike on the line (cycle WORLD, Dec. 1965).

With some 20 other good pros, the big names combined to stage heroic rides that made the San Diego-Phoenix desert derby of 1913 to 1920 as memorable as the nation's most punishing and brutal road race — and when there was a road it was a hold-over from the covered wagon trails.

A win here meant reams of good publicity for any manufacturer, and the 1913 race run on Oct. 31, Nov. 1-2 brought out 18 entries with a platoon of Indian riders headed by "Cannon Ball" Baker and Paul Derkum, the Los Angeles star, and backed up by Harry Weitzell, Ray Smith, Paul Keating, Lorenzo Boido, Robert Young, and Ellison Wilson.

The Excelsior team was J. L. McNew, John Leng, Clarence Biggs, and Ernest Binkley; Harley-Davidsons were ridden by Art Holmes and Frank Moeck. Ken Verrill and Jack Saint rode Henderson Fours, while Roy Artley was astride a Thor.

The Indian machines were all stock, two-speed, except Weitzell's.

Derkum had put on small U.S. auto tires and cemented them to the rims for the heavy going.

In order to safeguard riders against hardship, the race was run in three segments with overnight stops at Yuma, Ariz., 211 miles from San Diego; the second night control was Agua Caliente, Ariz., 116 miles away; and one third of the last leg of 94 miles into Phoenix was through a settled region.

The riders started from San Diego at 5:30 a.m., Oct. 31, at two-minute intervals and sped out through the mountains for 50 miles before hitting the desert where their troubles started. Ahead lay the Mammoth Dry Wash, Arizona's dreaded "Death Trail" and graveyard of the prairie schooner trains. It was bottomless sand dunes and impassable by auto, but those old time bike jockeys had a lot of faith.

It knocked out an iron-man like "Cannon Ball" Baker, but Paul Derkum, with no previous experience on the sand hills made it across on his stock Indian twin; he had worked up from 13th place at the start to 6th before this.

A friend of Derkum had given the boys permission to bounce across the big railroad bridge over the Colorado river instead of being ferried across.

Derkum now poured on the coal and reached Yuma, the first night stop, in first place, trailed by Ray Smith, Harry Weitzell, John Leng, Roy Artley, Art Holmes, and Lorenzo Boido in that order.

And the leader's time for the 211 tough miles was 7 hours 21 minutes, a full 30 minutes faster than the auto race record for this run.

With a 30 mph average for the entire trip, Derkum was the first to cross the finish line in Phoenix; followed by Ray Smith, Indian, 2nd; Harry Weitzell, Indian, 3rd; John Leng, Excelsior, 4th; Roy Artley, Thor, 5th; Lorenzo Boido, Indian, 6th; and Art Holmes and Frank Moeck on Harlevs, the last of eight finishers.

And the reasons for the ten who failed to make it are not hard to understand, when the adventures of some entries in practice for the 1914 race are considered.

The next year's desert derby was scheduled to finish just one day ahead of the opening of the Arizona State Fair at Phoenix, on November 5th, and a fat purse of $12,500 was put up for the 441 miles of torture for men and machines. At the finish line in front of the Board of Trade building, 45% would go to the winner; 25% for second; 12%, third; and 7% to the fourth survivor.

Then, or now, this kind of money deserved some close attention, and some of the boys went into strenuous practice to discover the secrets of spanning the torrid wastelands. What they learned was threatened when they nearly eliminated themselves before the race — with one or two it came close to being permanent.

One was Paul Frantzen, one of the Indian riders, who followed Roy Artley and George Currier, the Excelsior team, out of San Diego, and when he fell behind he took a short cut through the sand hills south of Holtville and then things happened.

After being thrown off and bruising his knee, Franzen pitched over a high bank and was partly buried in the sand slide that followed. Unable to lift his machine out, he tried to start the engine and damaged it beyond repair.

In the height of the afternoon heat, he started limping away on his twisted knee to look for help.

Sand crept into his shoes and made his feet raw so he threw these away and struggled ahead barefoot.

At about 8 o'clock he finally fell from exhaustion and slept, but about midnight he heard cattle bawling somewhere. Halfcrawling he staggered toward the sound he thought he heard. But it wasn't delirium; Mexican guerrillas were camped nearby with some cattle stolen from ranches they had raided. Some gave him sips of water from a dirty canteen, while most were excitedly arguing whether or not to shoot him; finally they put him on a horse and he was taken within walking distance of a railroad station where he boarded a train for Yuma. He was back on race day looking for more battles with nature at her worst.

Walter House and Harry Weitzell rode their Indians out on a practice run, too, and became separated in the same Holtville area where Franzen came to grief. First Weitzell plunged into a hole. It took him an hour to get out. He then encountered House on foot and his bike half-buried in soft sand. Both struggled to lift it and soon were exhausted in the terrific heat. After drinking the last water in their canteens, they revived and tied a rope to the stalled machine and Weitzell's Indian pulled it free. Luckily it still ran, and they pulled into Yuma a badly battered pair.

In Yuma, Harry Weitzell warned his teammate, Paul Derkum, by way of a quote in the daily paper: "Derkum better look out for those sand hills. If he flops into one and the boys are not close to pull him out, it's good night for him."

But the resourceful Derkum solved his own problems without help. On a practice run he broke down outside of El Centro, and with one pint of water hiked 13 miles into town, ordered some parts. When they arrived, he walked all the way back and repaired his machine, then rode it in. And so he, too, was on the line on race day along with all the Indian team: Baker, Weitzell, House, Boido, Franzen and Wilson.

Desert explorers Roy Artley, George Currier and John Leng were the Excelsior hopefuls; and Art Holmes, son of a San Diego dealer, Harry Crandall of Phoenix. Ray Smith would ride two-speed Harleys.

Who would ride a Flying Merkel and a Thor was not decided until before the start of the race.

By using the Holtville Cut-off to avoid Mammoth Wash, the 1914 race was shortened to 416 miles, but otherwise it wasn't a great improvement.

"When you're riding out there," remarked Cannon Ball, "you think you're about six inches from Hell."

Casualties among the desert demons began when Thomas, on an un-named machine, cracked up 30 miles out of San Diego; then the hazards of this nightmare-on-wheels struck down Paul Frenzen, Roy Artley, and Ray Smith, but George Currier kept his Excelsior going until he lost the decision to a big rock onlv 18 miles out of Yuma.

Title Insurance and Trust Co., San Diego, Calif.

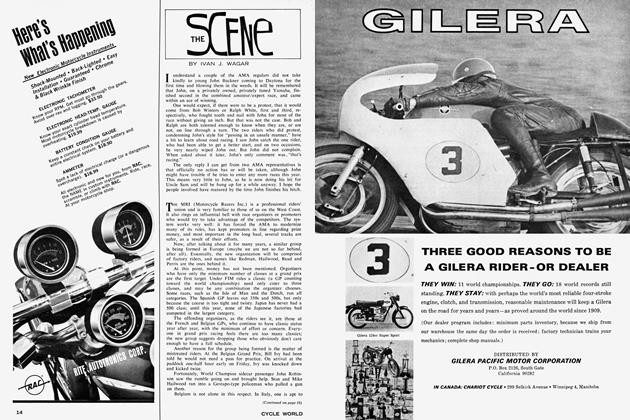

It began to look like "youth day" as 17 year-old Lorenzo Boido went ahead on his Indian twin; followed by Art Holmes, H-D; and in third on a Harley was Harry Crandall, who was only 16.

And this was the order at the finish with Boido hanging up a record for 405 miles of desert and mountains of 14 hours, 19 minutes. This mark stood for the next five years.

"Cannon Ball" Baker was not in this field; he was busy preparing for another rugged ramble of 530 miles in the Borderline Derby, scanning the mountains and desert from El Paso, Texas, to Phoenix, Arizona, starting on Nov. 9, 1914. Baker rode the same Indian Power-Plus 7 hp twin with which he set the coast-to-coast record that year; and proved his great endurance-riding ability by winning the Borderline event in 14 hours and 20 minutes. This was one minute over Boido's mark but 125 miles longer.

Increasing raids by Pancho Villa's Mexican rebel army bands into Arizona made any desert racing unsafe in 1915, but the next year a 441-mile race from Springerville, Arizona, to Phoenix was scheduled for Nov. 12th.

This attracted some new name riders: Joe Wolter, a star on the western motordrome circuit would try his luck dodging cactus, rattlesnakes, and bandits, on his fast Excelsior; AÍ Bedell, former transcontinental record holder, would be "Cannon Ball" Baker's teammate on an Indian, with Roy Artley and Jack Dodds as extra threats from the Springfield "Wigwam."

Harry Crandall and R. J. Orput represented Harley; and Arguile Davis and A. Meacham were Excelsior entries.

After drawing for starting places, the riders were dispatched at two-minute intervals from Springerville, one at a time, beginning at 8 a.m.

Roy Artley tore into Flagstaff, Arizona, the first control point, at 1:38 p.m. followed by AÍ Bedell two minutes later. Jack Dodds arrived at 3:34 and reported Orput out with a broken fork.

Near Winslow, "Cannon Ball" was giving Harry Crandall a hard chase, and Crandall topped a short hill way too fast and spilled as his bike took to the air just over the crest. Baker piled over the top and had to lock his wheel to keep from hitting Crandall lying across the road. This threw Baker into a slide that took him over a steep shoulder into a ravine which bent the frame and also Baker's leg. That they both weren't killed was due to the toughness of those old boys who rode the wild country.

The grim duel went on, and AÍ Meacham was the next victim of a wreck; then AÍ Bedell took a header over his handlebars and cut his head on a rock.

It was Roy Artley in first place at Phoenix after 13 hours, 2 minutes, and 2 seconds of the most rugged riding in North America. Blood-spattered AÍ Bedell was a sorry sight as he came in second, and it took six stitches by the medics to close his head cut.

Joe Wolter proved he could handle the rough stuff, too, and brought his Excelsior in third. With Jack Dodds fourth, the Indians had again proved their stamina by taking three out of the four first places.

After the end of World War I, Roy Artley became the coast's top road record maker; he rode an Indian to a Los Angeles-San Diego mark of 132 miles in 127 minutes; beat the motorcycle record from Los Angeles to San Francisco by 39 minutes and the auto record by 12 minutes; and added the San FranciscoFresno mark to his collection.

The one that bugged him was the San Diego-Phoenix record of 14 hours, 19 minutes set five years before by Lorenzo Boido. Changing to a Henderson Four, Artley attacked the mark after one trial run over the old course, but broke down outside of Phoenix.

After repairs were made, he started on the westward run on April 2, 1919, accompanied part way by Harry Crandall, Lee Holt, and H. Atterbaugh.

The barriers were just as tough taking the reverse direction toward San Diego. Outside of Yuma he spent 50 minutes cleaning a clogged carburetor, and his machine was checked in and out at Riley's Garage in Yuma exactly as the race entries were.

Artley had found a route that required only 394 miles to span the distance between the two cities, and reached San Diego in 13 hours, 10 minutes, for a new record. But it had taken him 1600 miles of desert riding in two weeks to accomplish this — which was an unparalleled performance in itself.

He could have waited until the 1920 renewal of the annual race, for again taking his trusty Indian road-burner he set a new record in the 416-mile grind to win in 12 hours, 28 minutes, which officially crowned him champ of desert daredevils and road king of the southwest.