The Adventures of Hoppy Hopkins

JAMES T. CROW

EVER THOUGHT OF putting in a season or two riding moto-cross in Europe? Ridden scrambles and hare and hounds and think maybe you wouldn’t find moto-cross all that much different? Think you’d like to give it a go?

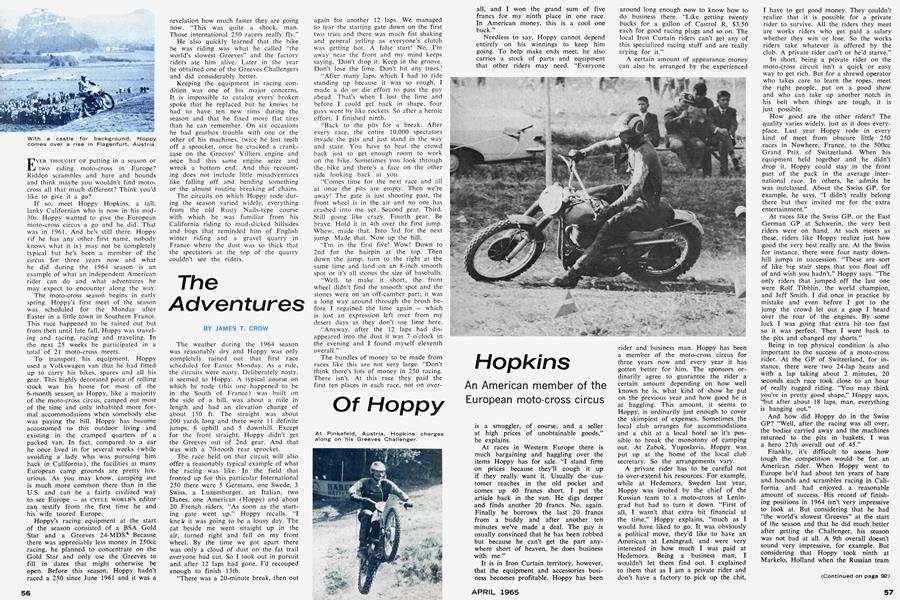

If so, meet Hoppy Hopkins, a tall, lanky Californian who is now in his mid-30s. Hoppy wanted to give the European moto-cross circus a go and he did. That was in 1961. And he’s still there. Hoppy (if he has any other first name, nobody knows what it is) may not be completely typical but he’s been a member of the circus for three years now and what he did during the 1964 season is an example of what an independent American rider can do and what adventures he may expect to encounter along the way.

The moto-cross season begins in early spring. Hoppy’s first meet of the season was scheduled for the Monday after Easter in a little town in Southern France. This race happened to be rained out but from then until late fall, Hoppy was traveling and racing, racing and traveling. In the next 25 weeks he participated in a total of 21 moto-cross meets.

To transport his equipment, Hoppy used a Volkswagen van that he had fitted up to carry his bikes, spares and all his gear. This highly decorated piece of rolling stock was his home for most of the 6-month season as Hoppy, like a majority of the moto-cross circus, camped out most of the time and only inhabited more formal accommodations when somebody else was paying the bill. Hoppy has become accustomed to this outdoor living and existing in the cramped quarters of a packed van. In fact, compared to a car he once lived in for several weeks (while avoiding a lady who was pursuing him back in California), the facilities at many European camp grounds are pretty luxurious. As you may know, camping out is much more common there than in the U.S. and can be a fairly civilized way to see Europe — as CYCLE WORLD’S editor cap testify from the first time he and his wife toured Europe.

Hoppy’s racing equipment at the start of the season consisted of a BSA Gold Star and a Greeves 24-MDS.' Because there was appreciably less money in 250cc racing, he planned to concentrate on the Gold Star and only use the Greeves to fill in dates that might otherwise be open. Before this season, Hoppy hadn’t raced a 250 since June 1961 and it was a revelation how much faster they are going now. “This was quite a shock, man. Those international 250 racers really fly.”

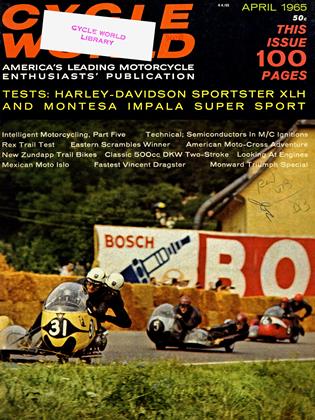

He also quickly learned that the bike he was riding was what he called “the world’s slowest Greeves” and the factory riders ate him alive. Later in the year he obtained one of the Greeves Challengers and did considerably better.

Keeping the equipment in racing condition was one of his major concerns.

It is impossible to catalog every broken spoke that he replaced but he knows he had to have ten new rims during the season and that he fixed more flat tires than he can remember. On six occasions he had gearbox trouble with one or the other of his machines, twice he lost teeth off a sprocket, once he cracked a crankcase on the Greeves’ Villiers engine and once had this same engine seize and wreck a bottom end. And this recounting does not include little misadventures like falling off and bending something or the almost routine breaking of chains.

The circuits on which Hoppy rode during the season varied widely, everything from the old Rusty Nails-type course with which he was familiar from his California riding to mud-slicked hillsides and bogs that reminded him of English winter riding and a gravel quarry in France where the dust was so thick that the spectators at the top of the quarry couldn’t see the riders.

The weather during the 1964 season was reasonably dry and Hoppy was only completely rained out that first race scheduled for Easter Monday. As a rule, the circuits were nasty. Deliberately nasty, it seemed to Hoppy. A typical course on which he rode (this one happened to be in the South of France) was built on the side of a hill, was about a mile in length and had an elevation change of about 150 ft. The straight was about 200 yards long and there were 11 definite jumps, 6 uphill and 5 downhill. Except for the front straight, Hoppy didn’t get the Greeves out of 2nd gear. And that was with a 70-tooth rear sprocket.

The race held on that circuit will also offer a reasonably typical example of what the racing was like. In the field that fronted up for this particular International 250 there were 5 Germans, one Swede, 3 Swiss, a Luxemburger, an Italian, two Danes, one American (Hoppy) and about 20 French riders. “As soon as the starting gate went up,” Hoppy recalls, “I kne4i it was going to be a lousy day. The cat beside me went straight up in the air, turned right and fell on my front wheel. By the time we got apart there was only a cloud of dust on the fat trail everyone had cut. So I took out in pursuit and after 12 laps had gone, I’d recouped enough to finish 13th.

“There was a 20-minute break, then out again for another 12 laps. We managed to tear the starting gate down on the first two tries and there was much fist shaking and general yelling as everyone’s clutch was getting hot. A false start! No, I’m away near the front and my mind keeps saying, ‘Don’t drop it. Keep in the groove. Don’t lose the lime. Don’t hit any trees.’

“After many laps, which I had to ride standing up because it was so rough, I made a do or die effort to pass the guy ahead. That’s when I lost the lime and before I could get back in shape, four guys went by like rockets. So after a heroic effort, I finished ninth.

“Back to the pits for a break. After every race, the entire 10,000 spectators invade the pits and just stand in the way and stare. You have to beat the crowd back just to get enough room to work on the bike. Sometimes you look through the bike and there’s a face on the other side looking back at you.

“Comes time for the next race and all at once the pits are empty. Then we’re away! The gate is just shooting past, the front wheel is in the air and no one has crashed into me yet. Second gear. Third. Still going like crazy. Fourth gear. Be brave. Hold it in 4th over the first jump. Whew, made that. Into 3rd for the next jump. Made that. Now up the hill.

“I’m in the first five! Wow! Down to 2nd for the hairpin at the top. Then down the jump, turn to the right at the same time and land on an 8-inch smooth spot or it’s all stones the size of baseballs.

“Well, to make it short, the front wheel didn’t find the smooth spot and the stones were on an off-camber part; it was a long way around through the brush before I regained the lime again — which is just an expression left over from my desert days as they don’t use lime here.

“Anyway, after the 12 laps had disappeared into the dust it was 7 o’clock in the evening and I found myself eleventh overall.”

The bundles of money to be made from races like this are not very large. “Don’t think there’s lots of money in 250 racing. There isn’t. At this race they paid the first ten places in each race, not on overall, and I won the grand sum of five francs for my ninth place in one race. In American money, this is a cool one buck.”

An American member of the European moto-cross circus

Needless to say, Hoppy cannot depend entirely on his winnings to keep him going. To help make ends meet, he also carries a stock of parts and equipment that other riders may need. “Everyone is a smuggler, of course, and a seller at high prices of unobtainable goods,” he explains.

At races in Western Europe there is much bargaining and haggling over the items Hoppy has for sale. “I stand firm on prices because they’ll cough it up if they really want it. Usually the customer reaches in the old pocket and comes up 40 francs short. I put the article back in the van. He digs deeper and finds another 20 francs. No, again. Finally he borrows the last 20 francs from a buddy and after another ten minutes we’ve made a deal. The guy is usually convinced that he has been robbed but because he can’t get the part anywhere short of heaven, he does business with me.”

It is in Iron Curtain territory, however, that the equipment and accessories business becomes profitable. Hoppy has been around long enough now to know how to do business there. “Like getting twenty bucks for a gallon of Castrol R, $3.50 each for good racing plugs and so on. The local Iron Curtain riders can’t get any of this specialized racing stuff and are really crying for it.”

A certain amount of appearance money can also be arranged by the experienced rider and business man. Hoppy has been a member of the moto-cross circus for three years now and every year it has gotten better for him. The sponsors ordinarily agree to guarantee the rider a certain amount depending on how well known he is, what kind of show he put on the previous year and how good he is at haggling. This amount, it seems to Hoppy, is ordinarily just enough to cover the skimpiest of expenses. Sometimes the local club arranges for accommodations and a chit at a local hotel so it’s possible to break the monotony of camping out. At Zabok, Yugoslavia, Hoppy was put up at the home of the local club secretary. So the arrangements vary.

A private rider has to be careful not to over-extend his resources. For example, while at Hedemora, Sweden last year, Hoppy was invited by the chief of the Russian team to a moto-cross at Leningrad but had to turn it down. “First of all, I wasn’t that extra bit financial at the time,” Hoppy explains, “much as I would have liked to go. It was obviously a political move, they’d like to have an American at Leningrad, and were very interested in how much I was paid at Hedemora. Being a business man, I wouldn’t let them find out. I explained to them that as I am a private rider and don’t have a factory to pick up the chit, I have to get good money. They couldn’t realize that it is possible for a private rider to survive. All the riders they meet are works riders who get paid a salary whether they win or lose. So the works riders take whatever is offered by the club. A private rider can’t or he’d starve.”

In short, being a private rider on the moto-cross circuit isn’t a quick or easy way to get rich. But for a shrewd operator who takes care to learn the ropes, meet the right people, put on a good show and who can take up another notch in his belt when things are tough, it is just possible.

How good are the other riders? The quality varies widely, just as it does everyplace. Last year Hoppy rode in every kind of meet from obscure little 250 races in Nowhere, France, to the 500cc Grand Prix of Switzerland. When his equipment held together and he didn’t drop it, Hoppy could stay in the front part of the pack in the average international race. In others, he admits he was outclassed. About the Swiss GP, for example, he says, “I didn’t really belong there but they invited me for the extra entertainment.”

At races like the Swiss GP, or the East German GP at Schwerin, the very best riders were on hand. At such meets as these, riders like Hoppy realize just how good the very best really are. At the Swiss for instance, there were four nasty downhill jumps in succession. “These are sort of like big stair steps that you float off of and wish you hadn’t,” Hoppy says. “The only riders that jumped off the last one were Rolf Tibblin, the world champion, and Jeff Smith. I did once in practice by mistake and even before I got to the jump the crowd let out a gasp I heard over the roar of the engines. By some luck I was going that extra bit too fast so it was perfect. Then I went back to the pits and changed my shorts.”

Being in top physical condition is also important to the success of a moto-cross rider. At the GP of Switzerland, for instance, there were two 24-lap heats and with a lap taking about 2 minutes, 20 seconds each race took close to an hour of really rugged riding. “You may think you’re in pretty good shape,” Hoppy says, ‘vbut after about 18 laps, man, everything is hanging out.”

And how did Hoppy do in the Swiss GP? “Well, after the racing was all over, the bodies carried away and the machines returned to the pits in baskets, I was a hero 27th overall out of 45.”

Frankly, it’s difficult to assess how tough the competition would be for an American rider. When Hoppy went to Europe he’d had about ten years of hare and hounds and scrambles racing in California and had enjoyed a reasonable amount of success. His record of finishing positions in 1964 isn’t very impressive to look at. But considering that he had “the world’s slowest Greeves” at the start of the season and that he did much better after getting the Challenger, his season was not bad at all. A 9th overall doesn’t sound very impressive, for example. But considering that Hoppy took ninth at Markelo, Holland when the Russian team was on hand with six CZs, ninth overall is damned good.

(Continued on page 92)

“Just in case anyone would like to try their hand here,” Hoppy says, “Remember that it will take about two years to change your style of riding to be suitable for European moto-cross. And there’s no such thing as a sleeper for a meeting here.”

There is more to being a member of the moto-cross circus than keeping your machine in shape and racing on weekends and holidays. There’s an abundance of transporting to be done, for one thing, and this can become very dull. Hoppy’s travels during the 1964 season covered 15,000 miles and that added up to a lot of long hard days of travel in a VW van which had a top speed, when healthy, of about 50 mph. And there were many times when the van wasn’t healthy at all. It still makes Hoppy tired just to remember all the trouble he had with it. Once, heading back for civilization after a trip in Scandinavia, he had the engine out three times in four days. “Before next season I have got to scrape up about 800 bucks for a Peugeot station wagon with a diesel in it. This is the only way to go. The VW has had it.”

It isn’t only the race-to-race hauling that adds to the miles but also the mandatory side trips. Every time the Greeves broke something important, for example, it meant another rush trip through Switzerland for Hoppy. There he knew a man who had the necessary pieces and it was either make the trip to Switzerland or not make it for the next race.

Twice during the season, Hoppy had free weekends that he used to rush back across the channel to his shop in London to rebuild his machinery and get ready for further assaults.

The social life of a moto-cross rider is pretty well taken care of. After almost every race there was a party sponsored by the local club. These, as a rule, were pretty lively affairs. “Girls really go for hero types,” Hoppy explains modestly, “and fortunately this extends to motocross racers.”

Hoppy liked most of the countries he traveled in during the season. His favorite was Hungary (“The Hungarian girls don’t wear bras and, man, your eyes don’t know where to look first!”) and the area he liked least was Scandinavia. It seemed to him that Americans were being fleeced on everything from booze to milk shakes. He did join up with a very nice traveling companion there, though, a blonde who was packing her own camping equipment but wasn’t so obsessed with the outdoor life that she objected to spending the rest of a week in a hotel. “And not only that, she spoke English,” Hoppy reminisces. “She was a real charmer, just about the right size all over and had a little tear ’em up smile that just did it.”

So the life of a moto-cross rider isn’t altogether celibate even though it is likely to be solitary much of the time. There are, however, an increasing number of American riders showing up in Europe every year and periodic get togethers are held (like the one last year at a strip club in Le Mans) where any tendencies toward homesickness can be dispelled. Among those Hoppy was with last year were Stu Peters, Paul Hunt and Dale Martin, all from California. Stu did quite well during the season, probably better than Hoppy. Paul Hunt came over to look around and rode a few moto-cross events in addition to the Six Days Trial (Hoppy says Paul rode better before putting a footpeg through his leg when he hit a tree in the Six Days). Dale Martin crewed for Hoppy for about six weeks and plans to make the circus on his own this year. These riders will be seeing more of each other during the winter as they keep their bikes in the same shop in London and use that as their headquarters.

Summing it all up, the geography Hoppy covered during the season extended from as far south as Spain, as far north as Stockholm, as far west as it is possible to go on the Brittany Peninsula and as far east as Budapest and Belgrade. He crossed and re-crossed the Iron Curtain without much difficulty as long as he stuck to two words, “Sport” and “Moto-cross,” which all the crossing guards seemed to understand and appreciate. He figures he was lucky, however, to get away with weaving in and out of an East German army convoy when his van had “U.S.A.” painted all over it.

Also, now that the season is over, Hoppy is forgetting the disgust and disappointment he experienced over the failure of his machines in so many races. He’s forgetting, too, the lousy circuits, the innumerable times he fell and the aches and pains that came from having bruises on top of bruises during the early part of the season. It doesn’t even matter much now that he left his home in London on a cold wet night in March and wound up a solid six months of adventure by being three hours late for a buddy’s wedding in Zurich. Or that he was no richer, or more handsome, or much smarter than he was when he started. The important part of the six months was that he got 21 race meets in 25 weeks and, to a moto-cross rider like Hoppy, this is really the only thing that counts. He says, “I’m spending the winter in bloody cold England, riding mud scrambles and waiting for spring. Just as soon as the season starts, I’ll be ready to go again. Only better next time.” •