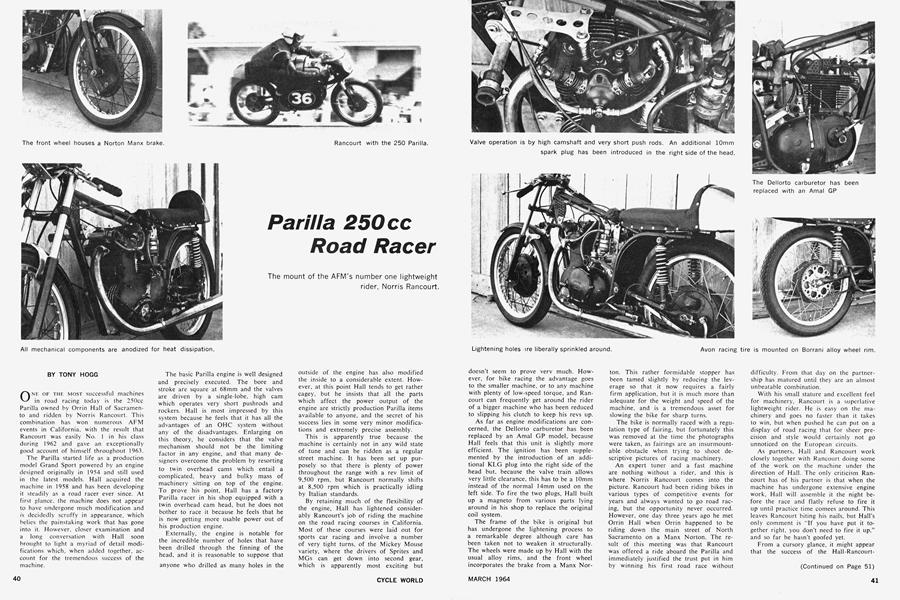

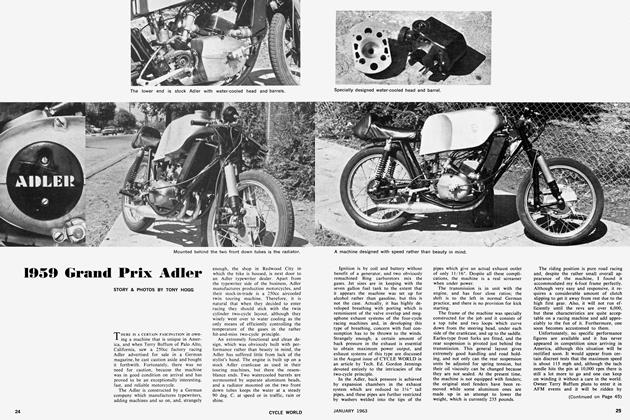

Parilla 250cc Road Racer

The mount of the AFM’s number one lightweight rider, Norris Rancourt.

TONY HOGG

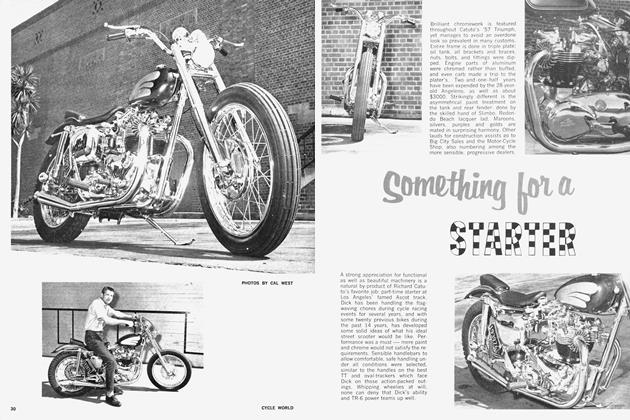

ONE OF THE MOST successful machines in road racing today is the 250cc Parilla owned by Orrin Hall of Sacramen-to and ridden by Norris Rancourt. This combination has won numerous AFM events in California, with the result that Rancourt was easily No. 1 in his class during 1962 and gave an exceptionally good account of himself throughout 1963.

The Parilia started life as a production model Grand Sport powered by an engine designed originally in 1954 and still used in the latest models. Hall acquired the machine in 1958 and has been developing it steadily as a road racer ever since. At first glance, the machine does not appear to have undergone much modification and is decidedly scruffy in appearance, which belies the painstaking work that has gone into it. However, closer examination and a long conversation with Hall soon brought to light a myriad of detail modifications which, when added together, account for the tremendous success of the machine.

The basic Parilia engine is well designed and precisely executed. The bore and stroke are square at 68mm and the valves are driven by a single-lobe, high cam which operates very short pushrods and rockers. Hall is most impressed by this system because he feels that it has all the advantages of an OHC system without any of the disadvantages. Enlarging on this theory, he considers that the valve mechanism should not be the limiting factor in any engine, and that many designers overcome the problem by resorting to twin overhead cams which entail a complicated, heavy and bulky mass of machinery sitting on top of the engine. To prove his point. Hall has a factory Parilia racer in his shop equipped with a twin overhead cam head, but he does not bother to race it because he feels that he is now getting more usable power out of his production engine.

Externally, the engine is notable for the incredible number of holes that have been drilled through the finning of the head, and it is reasonable to suppose that

anyone who drilled as many holes in the outside of the engine has also modified the inside to a considerable extent. However, at this point Hall tends to get rather cagey, but he insists that all the parts which affect the power output of the engine are strictly production Parilia items available to anyone, and the secret of his success lies in some very minor modifications and extremely precise assembly.

This is apparently true because the machine is certainly not in any wild state of tune and can be ridden as a regular street machine. It has been set up purposely so that there is plenty of power throughout the range with a rev limit of 9,500 rpm, but Rancourt normally shifts at 8,500 rpm which is practically idling by Italian standards.

By retaining much of the flexibility of the engine. Hall has lightened considerably Rancourt’s job of riding the machine on the road racing courses in California. Most of these courses were laid out for sports car racing and involve a number of very tight turns, of the Mickey Mouse variety, where the drivers of Sprites and MGs can get down into second gear, which is apparently most exciting but doesn’t seem to prove verv much. However, for bike racing the advantage goes to the smaller machine, or to any machine with plenty of low-speed torque, and Rancourt can frequently get around the rider of a bigger machine who has been reduced to slipping his clutch to keep his revs up.

As far as engine modifications are concerned, the Dellorto carburetor has been replaced by an Amal GP model, because Hall feels that this unit is slightly more efficient. The ignition has been supplemented by the introduction of an additional KLG plug into the right side of the head but, because the valve train allows very little clearance, this has to be a 10mm instead of the normal 14mm used on the left side. To fire the two plugs, Hall built up a magneto from various parts lying around in his shop to replace the original coil system.

The frame of the bike is original but has undergone the lightening process to a remarkable degree although care has been taken not to weaken it structurally. The wheels were made up by Hall with the usual alloy rims, and the front wheel incorporates the brake from a Manx Norton. This rather formidable stopper has been tamed slightly by reducing the leverage so that it now requires a fairly firm application, but it is much more than adequate for the weight and speed of the machine, and is a tremendous asset for slowing the bike for sharp turns.

The bike is normally raced with a regulation type of fairing, but fortunately this was removed at the time the photographs were taken, as fairings are an insurmountable obstacle when trying to shoot descriptive pictures of racing machinery.

An expert tuner and a fast machine are nothing without a rider, and this is where Norris Rancourt comes into the picture. Rancourt had been riding bikes in various types of competitive events for years and always wanted to go road racing, but the opportunity never occurred. However, one day three years ago he met Orrin Hall when Orrin happened to be riding down the main street of North Sacramento on a Manx Norton. The result of this meeting was that Rancourt was offered a ride aboard the Parilia and immediately justified the trust put in him by winning his first road race without difficulty. From that day on the partnership has matured until they are an almost unbeatable combination.

With his small stature and excellent feel for machinery, Rancourt is a superlative lightweight rider. He is easy on the machinery and goes no faster than it takes to win, but when pushed he can put on a display of road racing that for sheer precision and style would certainly not go unnoticed on the European circuits.

As partners. Hall and Rancourt work closely together with Rancourt doing some of the work on the machine under the direction of Hall. The only criticism Rancourt has of his partner is that when the machine has undergone extensive engine work, Hall will assemble it the night before the race and flatly refuse to fire it up until practice time comees around. This leaves Rancourt biting his nails, but Hall’s only comment is “If you have put it together right, you don’t need to fire it up.’’ and so far he hasn’t goofed yet.

From a cursory glance, it might appear that the success of the Hall-RancourtParilia team stems from drilling a lot of holes in an otherwise production machine. However, this is obviously not the case at all, and the results have been obtained by the combination of Norris Rancourt’s flair for riding lightweight road racers, and Orrin Hall’s wealth of experience, and the exceptional attention to detail which he puts into the preparation of the machine. Unfortunately, partnerships of this nature do not occur very often, but when they do, they are certainly hard to beat when the flag falls. •

(Continued on Page 51)

We have long since become utterly convinced that the single factor separating the winning machinery and the also-rans is how much attention has been given to detail in preparation. This Orrin Halltuned Parilia provides evidence to support that conviction. There are the obvious touches around the engine — such as the liberal drilling of the cylinder head finning — but closer inspection will reveal that the work has not ended there.

For example, the cylinder head nuts have been machined down to leave only that which is essential, and the entire engine (and items in the rest of the machine) have been given a dull black finish for improved heat dissipation. Air inlets have been provided in the front of the right-side crankcase side cover to cool the magneto, as this is a component that works very hard in a fast-turning racing engine. The clutch-rod actuating lever has a small strengthening rib welded on, and the lever itself lengthened, probably to recover a soft clutch actuation following the installation of some very heavy clutch springs. And, for some reason, the positions of the crankcase breather and filler have been reversed; the former is now around behind the cylinder.

It is also worth mentioning that the engine-mounting plates at the front down tube are now made of aluminum. Those at the back of the transmission are welded into the frame and must, therefore, be made of steel. There are other bits and pieces made of aluminum: the struts that hold the fairing and the cylinder head stay are examples. Throughout the rest of the machine, the same shaving of ounces is apparent. There are aluminum supports for the front fender, and even the front brake’s cam levers have been trimmed for lightness. The extent of Hall’s fanaticism is betrayed by the fact that he has even drilled out the centers of bolts and counterbored into bolt heads just to remove a few additional ounces. This might seem to be carrying matters to a ridiculous extreme, but there are few large bits that may be safely chopped away on a motorcycle, and the painstaking removal of trifles is the only means of producing a lighter machine than one’s rivals. Carry this “nothing too small” philosophy to its logical conclusion and you will find that you have invested an incredible number of hours — and you will also find yourself winning races. Ed. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue