a visit to Two-Stroke Castle

HEINZ-JURGEN SCHNEIDER

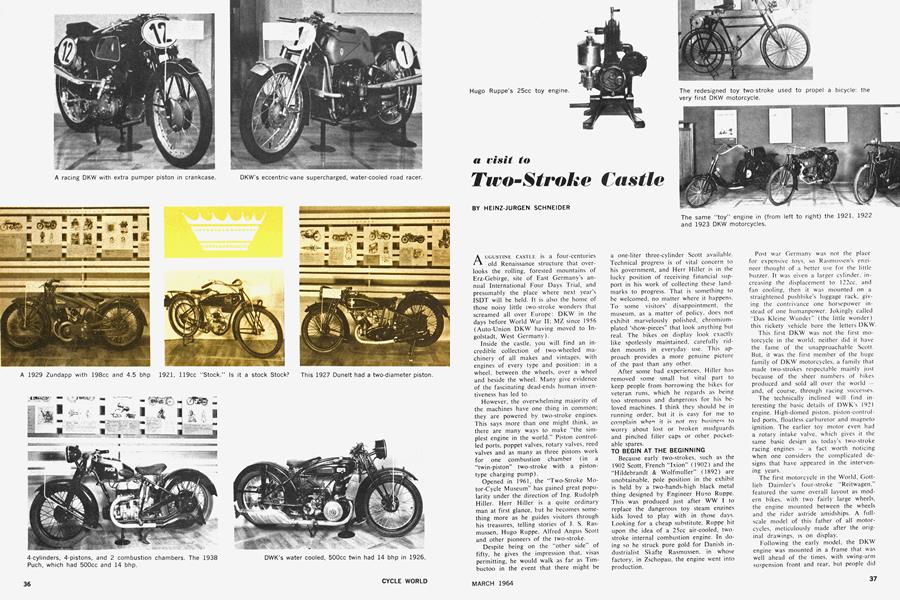

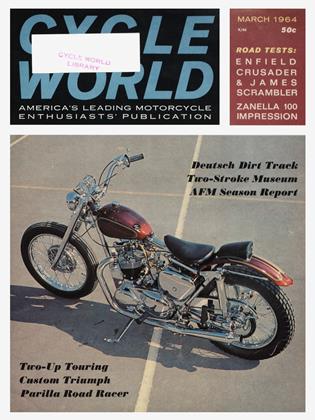

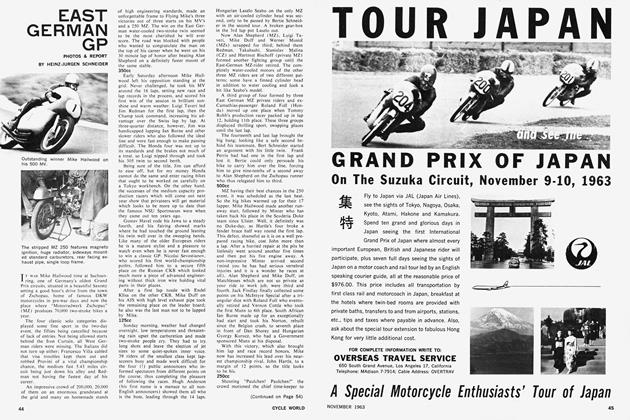

AUGUSTINE CASTLE is a four-centuries old Renaissance structure that overlooks the rolling, forested mountains of Erz-Gebirge, site of East Germany’s annual International Four Days Trial, and presumably the place where next year’s ISDT will be held. It is also the home of those noisy little two-stroke wonders that screamed all over Europe: DKW in the days before World War II; MZ since 1956 (Auto-Union DKW having moved to Ingolstadt, West Germany).

Inside the castle, you will find an incredible collection of two-wheeled machinery of all makes and vintages, with engines of every type and position: in a wheel, between the wheels, over a wheel and beside the wheel. Many give evidence of the fascinating dead-ends human inventiveness has led to.

However, the overwhelming majority of the machines have one thing in common; they are powered by two-stroke engines. This says more than one might think, as there are many ways to make “the simplest engine in the world." Piston controlled ports, poppet valves, rotary valves, reed valves and as many as three pistons work for one combustion chamber (in a “twin-piston” two-stroke with a pistontype charging pump).

Opened in 1961, the “Two-Stroke Motor-Cycle Museum” has gained great popularity under the direction of Ing. Rudolph Hiller. Herr Hiller is a quite ordinary man at first glance, but he becomes something more as he guides visitors through his treasures, telling stories of J. S. Rasmussen, Hugo Ruppe, Alfred Angus Scott and other pioneers of the two-stroke.

Despite being on the “other side ' of fifty, he gives the impression that, visas permitting, he would walk as far as Timbuctoo in the event that there might be

a one-liter three-cylinder Scott available. Technical progress is of vital concern to his government, and Herr Hiller is in the lucky position of receiving financial support in his work of collecting these landmarks to progress. That is something to be welcomed, no matter where it happens. To some visitors’ disappointment, the museum, as a matter of policy, does not exhibit marvelously polished, chromiumplated ‘show-pieces” that look anything but real. The bikes on display look exactly like spotlessly maintained, carefully ridden mounts in everyday use. This approach provides a more genuine picture of the past than any other.

After some bad experiences, Hiller has removed some small but vital part to keep people from borrowing the bikes for veteran runs, which he regards as being too strenuous and dangerous for his beloved machines. I think they should be in running order, but it is easy for me to complain when it is not my business to worry about lost or broken mudguards and pinched filler caps or other pocketable spares.

TO BEGIN AT THE BEGINNING

Because early two-strokes, such as the 1902 Scott, French “Ixion” (1902) and the “Hildebrandt & Wolfmuller” (1892) are unobtainable, pole position in the exhibit is held by a two-hands-high black metal thing designed by Engineer Hueo Ruppe. This was produced just after WW I to replace the dangerous toy steam engines kids loved to play with in those days. Looking for a cheap substitute, Ruppe hit upon the idea of a 25cc air-cooled, twostroke internal combustion engine. In doing so he struck pure gold for Danish industrialist Skafte Rasmussen, in whose factory, in Zschopau, the engine went into production.

Post war Germany was not the place for expensive toys, so Rasmussen’s engineer thought of a better use for the little buzzer. It was given a larger cylinder, increasing the displacement to 122cc, and fan cooling, then it was mounted on a straightened pushbike’s luggage rack, giving the contrivance one horsepower instead of one humanpower. Jokingly called “Das Kleine Wunder” (the little wonder) this rickety vehicle bore the letters DKW.

This first DKW was not the first motorcycle in the world; neither did it have the fame of the unapproachable Scott. But, it was the first member of the huge family of DKW motorcycles, a family that made two-strokes respectable mainly just because of the sheer numbers of bikes produced and sold all over the world — and, of course, through racing successes.

The technically inclined will find interesting the basic details of DWK’s 1921 engine. High-domed piston, piston-controlled ports, floatless carburetor and magneto ignition. The earlier toy motor even had a rotary intake valve, which gives it the same basic design as today's two-stroke racing engines — a fact worth noticing when one considers the complicated designs that have appeared in the intervening years.

The first motorcycle in the World, Gottlieb Daimler's four-stroke “Reitwagen. featured the same overall layout as modern bikes, with two fairly large wheels, the engine mounted between the wheels and the rider astride amidships. A fullscale model of this father of all motorcycles, meticulously made after the original drawings, is on display.

Following the early model, the DKW engine was mounted in a frame that was well ahead of the times, with swing-arm suspension front and rear, but people did not like the more advanced designs and in 1922 DKW returned to conventional practice. The engine, which had then been enlarged to 142cc and had 1.5 bhp. was mounted in a rigid-type frame with a pendulum-type front suspension (a nearly rigid type of front fork which allowed the wheel to travel fore-and-aft: not up and down). This model was neither cheaper nor better than the others, but more favorably received by the buying public — a factor to keep an eye on. even today.

This belt-driven “Reichsfahrt-Modell,” still sporting pedals like a moped, really began the motorization of German transport. After two years of production with this model, DKW dropped the pedals and the cooling fan. built a new engine having 2.5 bhp and 175cc and installed it in a pressed-steel frame, something unheard-of in 1924.

YEARS OF TRIAL AND ERROR (1920-1939)

Almost all successful, enduring motorcycle designs, and most of the Augustusburg exhibits, show ordinary features, proving how little really new has been found during the last 40 years of development. The best thing to do with most of this mass of machinery is to ignore it and devote our reporting to the many extremely unusual models designed in an out-of-the-ordinary manner in an attempt to improve power output or reliability to an extent believed unobtainable with simpler devices.

Although it was known then, as now. that manifolding and porting should be straight, smooth and free of obstacles to be efficient, this fact was continually disregarded by the engine manufacturers. So was the simple physical fact that gases have mass, or weight, and thus resist being forced into motion or stopping once in motion. This gas-flow inertia is utilized greatly in today’s engines, making more advantageous port timing possible.

Also, acoustical factors were ignored. No use was made of the pressure waves reflecting back and forth in the engine’s manifolding. Engineers today have put this phenomenon to use most effectively, employing the pressure waves to force back into the cylinder a portion of the fresh charge that would otherwise be lost down the exhaust pipe. That gives a small, but highly important supercharging effect. (Adler exhausts, Jan. 1963 CYCI.F. WORTD.)

As is true now. people buying motorcycles in the pre-WW II years held brute power in high esteem. In engineering terms, there is a lot of brute force in supercharging. In two-stroke design, the shortcomings of crankcase scavenging were often regarded as reason enough for supercharging. Or. one might try to improve the crankcase, as a pump, by improving the ratio of the volume swept by the piston. to the total crankcase volume. Dunelt did so in 1926, with an eneine having a piston and cylinder with different diameters in their upper and lower portions. The piston’s lower part, which worked as a pump, had a larger diameter than the combustion chamber end and increased both the volume and pressure of scavenging air.

Although this idea looks clever indeed, the piston was too heavy, and there were thermal problems too difficult to overcome with the alloys available at the time, so the idea proved to be a failure. Nevertheless, Ewald Kluge, in later years a works rider for DKW and European champion, started his career on a racing version of a motorcycle powered by this 25()cc engine.

A further step toward supercharging was an auxiliary piston called a charging pump. Moving in a large-bore cylinder below the crankcase and operated (by connecting rod) from the crankshaft, it vastly improved the crankcase’s effectiveness as part of a scavenging pump. Although not now in use, for a variety of reasons, this feature was employed in the DKW racing bikes that won so many races and championships during the 15 years preceding WW 11. However, the 1939 models had rotary superchargers.

Relatively low crankcase temperatures and pressures make the two-stroke (at least, the crankcase-scavenged variety) particularly well suited to rotary valves — the disc-type valve being best because of mechanical and air-flow advantages. In spite of the highly-improved breathing obtainable with rotary intake valves, they were seldom used during the years of trial and error. Piston-controlled ports were used almost exclusively, and this arrangement does not lend itself to supercharging.

In recognition of this fact, Auto Union introduced some bits from a mouth-organ into racing engineering. These bits were the thin steel reeds that vibrate open and closed in a “harmonica.” For the racing engines, these reeds were used as one-way valves, which would let the air/fuel mixture flow into the engine’s crankcase, but would be blown shut if the flow reversed.

Good idea though it was (and it is back in use today) the reed valve was a practical failure, as the reeds kept breaking due to vibrations, and there was an excessive pressure drop across the complicated flow path provided by these thin strips of metal. In 1930, however, there was a production-type DKW. an 1 1 bhp, 350cc single, with a reed-valve system that saved one port by combining the intake and exhaust window — the reeds prevented exhaust gases from blowing back through the carburetor, and vice versa. May I ask for what purpose this was done?

One way to improve gas flow' into and from the cylinder that was developed was a twin-cylinder engine in which both cylinders shared a single combustion chamber. One of the pistons controlled the transfer ports; the other the exhaust ports. This system gave a better separation of exhaust gases and the fresh charge, which reduced the small losses of the fresh charge, but today the same thing is more easily achieved by a well-designed exhaust pine cum expansion and resonant chamber.

Many of DKW’s racing bikes were made after this pattern and Puch still follows these lines.

In the twin-piston two-stroke, both pistons are often connected to the same rod. but engines have been made in which the con-rod system gives an “advance" to the exhaust piston, which provides a more favorable asymmetrical exhaust and transfer timing.

An astonishing feature of the 500cc Puch on display is its engine, which has four pistons and cylinders, arranged as a “square,” working from a single crankshaft and having two combustion chambers. This engine was. in effect, a pair of the twin-piston “singles" Puch produces even now. This machine is also unusual in having its clutch in the rear wheel hub. Some early Puch models even had their two-speed transmissions in the same place. The reason for this was apparently that Puch engineers wanted to transmit low torque at high chain speeds. Good heavens! Why?

A weak point of the twin-piston “single,” and probably the sole reason it is not used more often, is the restriction to gas flow given by the narrow combustion chamber connecting the tw'o cylinders — through which the gas-flow has to squeeze. I hat hampers breathing too much for high-speed operation.

An earlier, and more promising kind of twin-piston two-stroke engine is not the inverted-U type, like the Puch, but the one having a single cylinder, ouen at both ends, with opposed pistons. To the best of my knowledge this type goes back to the ideas of aircraft engineer Junkers, and the last time I saw it w'as in the 125cc unit built by MZ in 1954 for their racing bikes. It was never actually used in competition. The Japanese are said to have done some research recently on this type.

The system is quite simple: tw'o crankshafts, connected by a chain, or train of gears, run at each end of a long cylinder and operate two opposed pistons. In supercharged versions, the good gas-flow characteristics of the type make it attractive. but as blowers are prohibited in racing now, it looks difficult to make use of any of the advantages of the system.

Piston design and the placing of transfer ports shows best the progress of sophisticated gas-flow techniques. From nose-shaped piston crowms and a single transfer port, design has progressed through various fancy layouts with many ports distributed around the circumference of the barrel, and we have come back almost full-circle to Schnurle’s two-port scavenging and flat piston crown. Until very recently, this system was regarded as a non plus ultra; now with the three-port scavenging begun at MZ. the cycle begins again.

A most interesting, although hopeless item in the collection is a 1924 engine with an upside-down piston: the so-called “cup piston" that was intended to give high power output because of little chargeloss and effective scavenging. It must have caused much distress among the engineers concerned, with sealing, balancing and reliability problems. And it did not have piston rings.

A rare design, and one to be admired, is the “poor man’s” BMW. the 350cc MZ BK, the only two-stroke, flat-twin production bike I know (Ed. Note: the Velocette Viceroy scooter engine is a two-stroke opposed-twin. This ten-year-old design, incidentally. won its sidecar class in a 1963 Berlin 24-hours race.

Drawings and photographs give evidence of the one-time existence of a 1939 Italian 5()0cc Galbusera, a supercharged V-8. Also, there is the intriguing 1923 Steininger, with its still up-to-date water cooling. The cast light-alloy water container attached directly to the cylinder without any rubber tubes.

And in the sheds, away from the main collection, there are famous vintage fourstrokes. An in-line four Danish Nimbus; the endlessly long, single-cylinder Bohmerland which could easily carry three persons at one time . . . These bikes are being restored and will be exchanged for two-stroke motorcycles from other collections — which money alone could not buy. Any offers?

The super-abundance of motorcycles enabled Herr Hiller to write a very concise 96-page booklet on the history of two-stroke motorcycles, which does not really say all there is to say about them. This proves how far-reaching a subject it is, and how' little can be covered in a short report.

SOME OUTLOOKS

Although it is already valuable to the general public, Mr. Hiller wants his museum used for an even more important purpose. Room and money permitting the library will be extended. Also there will be studios for members of nearby Dresden Technical University. This is an idea leading further than its initiator may think, as he not only wants his guests to study what the pioneers of motorcycling have done, he wants them to revive forgotten ideas with modern knowledge and today’s machining facilities, with improved materials. This is an idea to be supported.

Once highly successful engineering failures, which were successful only at their time and completely wrong when measured with a detached yardstick, had thoughtlessly designed frames, weak in spite of their heaviness, which were improved every year and were still silly until the triangular system with straight tubes was “discovered.” All should give reason for the young engineer to ponder over the question of whether technical progress is a straight-forward business, or if it is nothing but wrong premises cultivated to the highest extent with all the human mind can do. but still a dead end which has to be replaced by ideas which will only be newer wrong premises. •