Deutsch Dirt Track

SIDNEY DICKSON

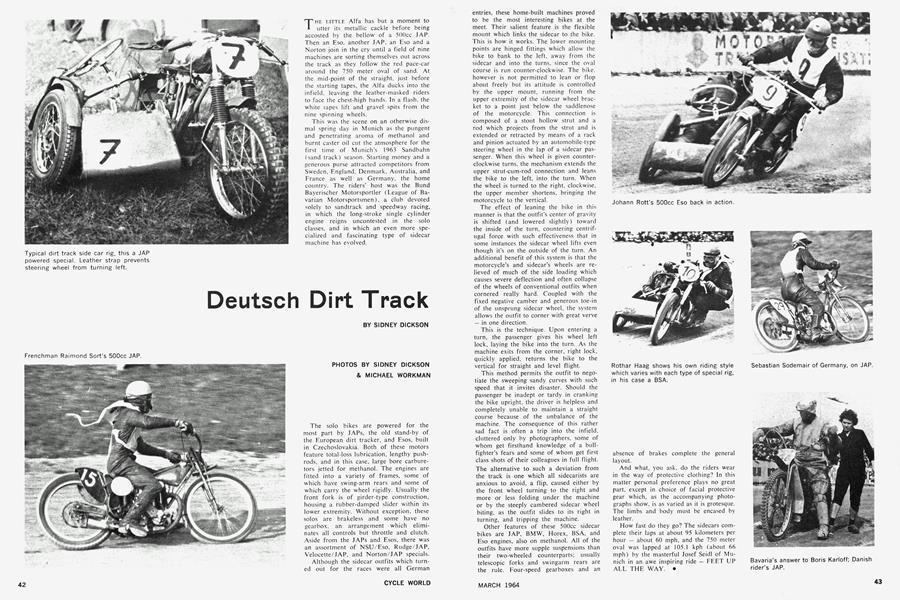

THE LITTLE Alfa has but a moment to utter its metallic cackle before being accosted by the bellow of a 500cc JAP. Then an Eso, another JAP, an Eso and a Norton join in the cry until a field of nine machines are sorting themselves out across the track as they follow the red pace-car around the 750 meter oval of sand. At the mid-point of the straight, just before the starting tapes, the Alfa ducks into the infield, leaving the leather-masked riders to face the chest-high bands. In a flash, the white tapes lift and gravel spits from the nine spinning wheels.

This was the scene on an otherwise dismal spring day in Munich as the pungent and penetrating aroma of methanol and burnt caster oil cut the atmosphere for the first time of Munich’s 1963 Sandbahn (sand track) season. Starting money and a generous purse attracted competitors from Sweden, England, Denmark. Australia, and France as well as Germany, the home country. The riders’ host was the Bund Bayerischer Motorsportler (League of Bavarian Motorsportsmen), a club devoted solely to sandtrack and speedway racing, in which the long-stroke single cylinder engine reigns uncontested in the solo classes, and in which an even more specialized and fascinating type of sidecar machine has evolved.

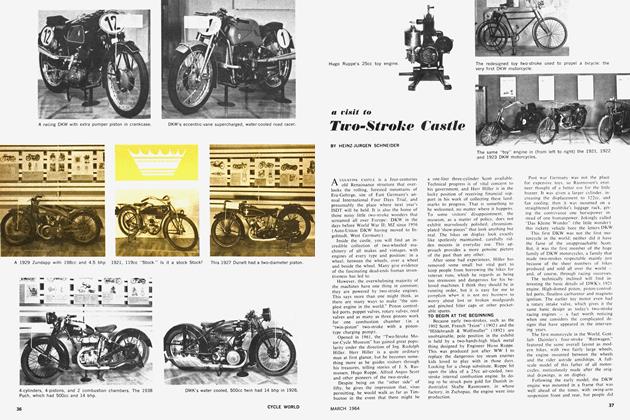

The solo bikes are powered for the most part by JAPs, the old stand-by of the European dirt tracker, and Esos, built in Czechoslovakia. Both of these motors feature total-loss lubrication, lengthy pushrods, and in this case, large bore carburetors jetted for methanol. The engines are fitted into a variety of frames, some of which have swing-arm rears and some of which carry the wheel rigidly. Usually the front fork is of girder-type construction, housing a rubber-damped slider within its lower extremity. Without exception, these solos are brakeless and some have no gearbox, an arrangement which eliminates all controls but throttle and clutch. Aside from the JAPs and Esos, there was an assortment of NSU/Eso, Rudge/JAP. Velocette/JAP, and Norton/JAP specials.

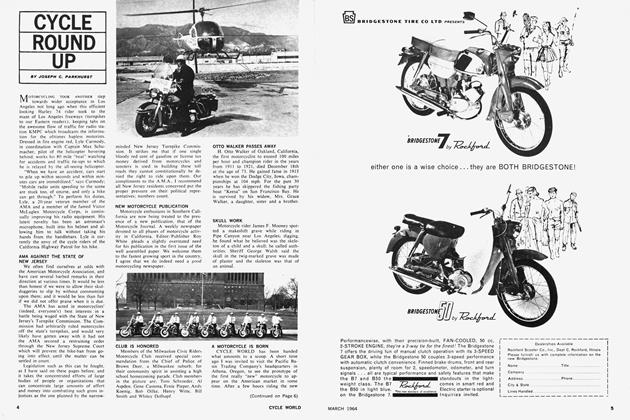

Although the sidecar outfits which turned out for the races were all German entries, these home-built machines proved to be the most interesting bikes at the meet. Their salient feature is the flexible mount which links the sidecar to the bike. This is how it works. The lower mounting points are hinged fittings which allow the bike to bank to the left, away from the sidecar and into the turns, since the oval course is run counter-clockwise. The bike, however is not permitted to lean or flop about freely but its attitude is controlled by the upper mount, running from the upper extremity of the sidecar wheel bracket to a point just below the saddlenosc of the motorcycle. This connection is composed of a stout hollow strut and a rod which projects from the strut and is extended or retracted by means of a rack and pinion actuated by an automobile-type steering wheel in the lap of a sidecar passenger. When this wheel is given counterclockwise turns, the mechanism extends the upper strut-cum-rod connection and leans the bike to the left, into the turn. When the wheel is turned to the right, clockwise, the upper member shortens, bringing the motorcycle to the vertical.

The effect of leaning the bike in this manner is that the outfit’s center of gravity is shifted (and lowered slightly) toward the inside of the turn, countering centrifugal force with such effectiveness that in some instances the sidecar wheel lifts even though it’s on the outside of the turn. An additional benefit of this system is that the motorcycle’s and sidecar’s wheels are relieved of much of the side loading which causes severe deflection and often collapse of the wheels of conventional outfits when cornered really hard. Coupled with the fixed negative camber and generous toe-in of the unsprung sidecar wheel, the system allows the outfit to corner with great verve — in one direction.

This is the technique. Upon entering a turn, the passenger gives his wheel left lock, laying the bike into the turn. As the machine exits from the corner, right lock, quickly applied, returns the bike to the vertical for straight and level flight.

This method permits the outfit to negotiate the sweeping sandy curves with such speed that it invites disaster. Should the passenger be inadept or tardy in cranking the bike upright, the driver is helpless and completely unable to maintain a straight course because of the unbalance of the machine. The consequence of this rather sad fact is often a trip into the infield, cluttered only by photographers, some of whom get firsthand knowledge of a bullfighter’s fears and some of whom get first class shots of their colleagues in full flight. The alternative to such a deviation from the track is one which all sidecarists are anxious to avoid, a flip, caused either by the front wheel turning to the right and more or less folding under the machine or by the steeply cambered sidecar wheel biting, as the outfit slides to its right in turning, and tripping the machine.

Other features of these 500cc sidecar bikes are JAP, BMW, Horex, BSA, and Eso engines, also on methanol. All of the outfits have more supple suspensions than their two-wheeled counterparts; usually telescopic forks and swingarm rears are the rule. Four-speed gearboxes and an absence of brakes complete the general layout.

And what, you ask, do the riders wear in the way of protective clothing? In this matter personal preference plays no great part, except in choice of facial protective gear which, as the accompanying photographs show, is as varied as it is grotesque. The limbs and body must be encased by leather.

How fast do they go? The sidecars complete their laps at about 95 kilometers per hour — about 60 mph, and the 750 meter oval was lapped at 105.1 kph (about 66 mph) by the masterful Josef Seidl of Munich in an awe inspiring ride — FEET UP ALL THE WAY. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue