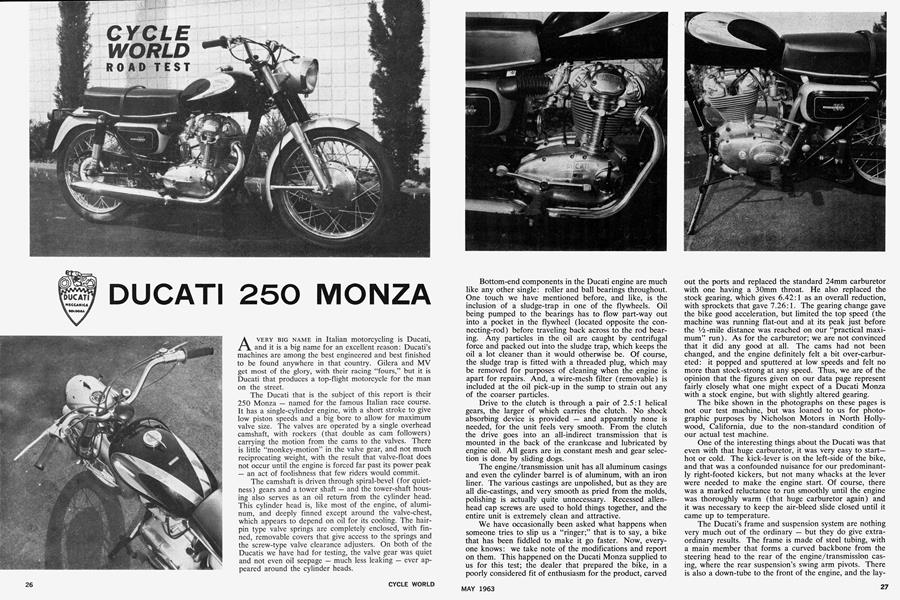

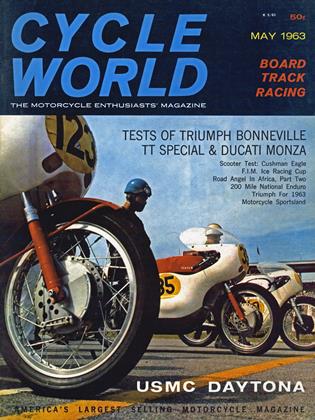

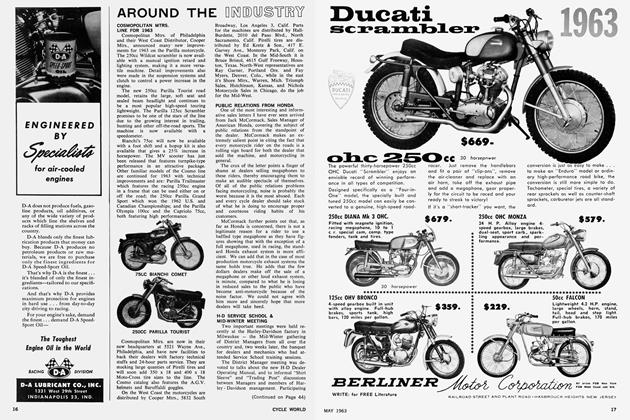

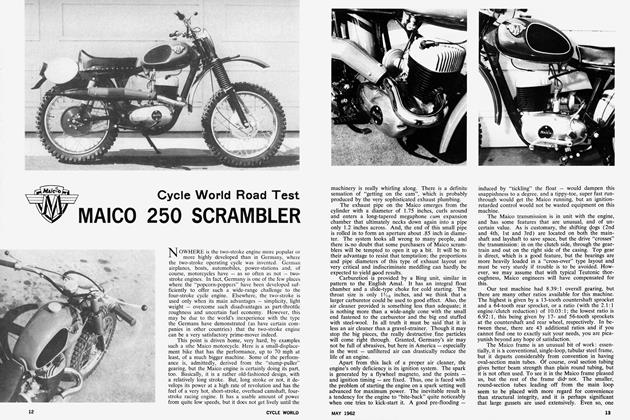

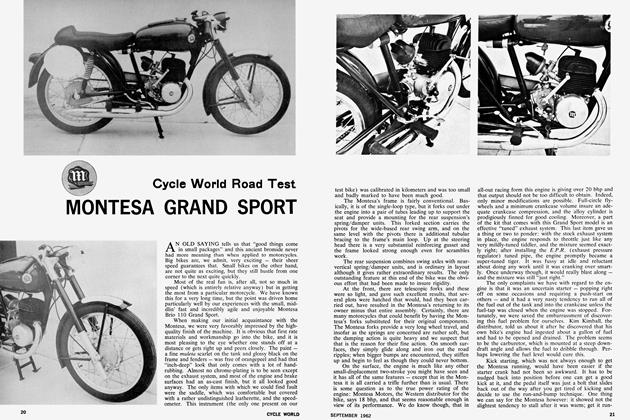

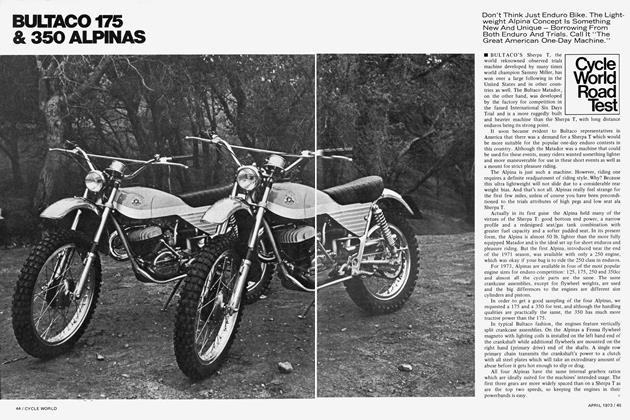

DUCATI 250 MONZA

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

A VERY BIG NAME in Italian motorcycling is Ducati, and it is a big name for an excellent reason: Ducati's machines are among the best engineered and best finished to be found anywhere in that country. Gilera and MV get most of the glory, with their racing "fours," but it is Ducati that produces a top-flight motorcycle for the man on the street.

The Ducati that is the subject of this report is their 250 Monza - named for the famous Italian race course. It has a single-cylinder engine, with a short stroke to give low piston speeds and a big bore to allow for maximum valve size. The valves are operated by a single overhead camshaft, with rockers (that double as cam followers) carrying the motion from the cams to the valves. There is little "monkey-motion" in the valve gear, and not much reciprocating weight, with the result that valve-float does not occur until the engine is forced far past its power peak - an act of foolishness that few riders would commit.

The camshaft is driven through spiral-bevel (for quiet ness) gears and a tower shaft - and the tower-shaft hous ing also serves as an oil return from the cylinder head. This cylinder head is, like most of the engine, of alumi num, and deeply finned except around the valve-chest, which appears to depend on oil for its cooling. The hair pin type valve springs are completely enclosed, with fin ned, removable covers that give access to the springs, and the screw-type valve clearance adjusters. On both of the Ducatis we have had for testing, the valve gear was quiet and not even oil seepage - much less leaking - ever ap peared around the cylinder heads.

Bottom-end components in the Ducati engine are much like any other single: roller and ball bearings throughout. One touch we have mentioned before, and like, is the inclusion of a sludge-trap in one of the flywheels. Oil being pumped to the bearings has to flow part-way out into a pocket in the flywheel (located opposite the connecting-rod) before traveling back across to the rod bearing. Any particles in the oil are caught by centrifugal force and packed out into the sludge trap, which keeps the oil a lot cleaner than it would otherwise be. Of course, the sludge trap is fitted with a threaded plug, which may be removed for purposes of cleaning when the engine is apart for repairs. And, a wire-mesh filter (removable) is included at the oil pick-up in the sump to strain out any of the coarser particles.

Drive to the clutch is through a pair of 2.5:1 helical gears, the larger of which carries the clutch. No shock absorbing device is provided — and apparently none is needed, for the unit feels very smooth. From the clutch the drive goes into an all-indirect transmission that is mounted in the back of the crankcase and lubricated by engine oil. All gears are in constant mesh and gear selection is done by sliding dogs.

The engine/transmission unit has all aluminum casings and even the cylinder barrel is of aluminum, with an iron liner. The various castings are unpolished, but as they are all die-castings, and very smooth as pried from the molds, polishing is actually quite unnecessary. Recessed alienhead cap screws are used to hold things together, and the entire unit is extremely clean and attractive.

We have occasionally been asked what happens when someone tries to slip us a "ringer;" that is to say, a bike that has been fiddled to make it go faster. Now, everyone knows: we take note of the modifications and report on them. This happened on the Ducati Monza supplied to us for this test; the dealer that prepared the bike, in a poorly considered fit of enthusiasm for the product, carved

out the ports and replaced the standard 24mm carburetor with one having a 30mm throat. He also replaced the stock gearing, which gives 6.42:1 as an overall reduction, with sprockets that gave 7.26:1. The gearing change gave the bike good acceleration, but limited the top speed (the machine was running flat-out and at its peak just before the Vi-mile distance was reached on our "practical maximum" run). As for the carburetor; we are not convinced that it did any good at all. The cams had not been changed, and the engine definitely felt a bit over-carbureted: it popped and sputtered at low speeds and felt no more than stock-strong at any speed. Thus, we are of the opinion that the figures given on our data page represent fairly closely what one might expect of a Ducati Monza with a stock engine, but with slightly altered gearing.

The bike shown in the photographs on these pages is not our test machine, but was loaned to us for photographic purposes by Nicholson Motors in North Hollywood, California, due to the non-standard condition of our actual test machine.

One of the interesting things about the Ducati was that even with that huge carburetor, it was very easy to starthot or cold. The kick-lever is on the left-side of the bike, and that was a confounded nuisance for our predominantly right-footed kickers, but not many whacks at the lever were needed to make the engine start. Of course, there was a marked reluctance to run smoothly until the engine was thoroughly warm (that huge carburetor again) and it was necessary to keep the air-bleed slide closed until it came up to temperature.

The Ducati's frame and suspension system are nothing very much out of the ordinary — but they do give extraordinary results. The frame is made of steel tubing, with a main member that forms a curved backbone from the steering head to the rear of the engine/transmission casing, where the rear suspension's swing arm pivots. There is also a down-tube to the front of the engine, and the layout gives the equivalent of a single-loop frame. Enough clearance has been provided around the top of the engine to permit easy servicing in that area.

No special feature distinguishes the front forks, but as we said, they give extraordinary results. The springing is soft, and the damping very firm, and the combination of rake and trail must be good, for no tendency toward fork-flutter ever appeared. A steering damper is provided, but the only function it apparently serves is to keep the steering from being unduly sensitive. The steering is very precise, probably because the forks have been made exceptionally rigid. The axle is clamped very solidly, which lends rigidity to the forks as a whole, and there is a heavy strap bridging between the moving legs that serves as a fender bracket and as further reinforcement for the forks themselves. As elsewhere on the Ducati, there is a considerable amount of light alloy in evidence.

Full-width, light alloy brakes are a feature, and they are light and powerful in action — being, at times, almost too powerful if the rider clamps them on with more vigor than finesse. Also, they had a rather spongy feel that made it somewhat difficult to sense how much braking force was being applied. However, we used them quite hard for a number of laps around the difficult and demanding Riverside Raceway and they gave no trouble except when used clumsily — and it can be argued, with some logic, that such things are a problem for the rider; not for the people who make the machine.

A good, comfortable riding position, in combination with a good, soft seat, made riding the Ducati a special pleasure. The handlebars are not much for flat-on-the tank racing, but are excellently arranged for touring, and the various control levers, buttons and switches are located near to hand. The only thing we did not care for was the fact that the clutch and brake levers did not have ball-ends (a recent wounding has made us sensitive on this point).

The gear-shift control is a rocker-type pedal, which we prefer to the single-lever, toe-lift variety, and it gave clean, positive engagements — as it should. Some trouble was experienced, at first, with the transmission's unwillingness to dab into top gear as neatly as it did into the other three, but we soon learned to apply more pressure and that ended the difficulty. The transmission ratios are especially well staged; a trifle wide for racing, but perfect for touring.

Speedometer error was very great, but we have reason to believe that this is not typical. Actually, the instrument was in the process of breaking even as we made our speedometer calibration runs, and before the testing was completed, it had completely fallen apart. While it worked, it gave steady, if rather misleading, readings.

One item that we disliked so much that we removed it was the lean-stand. The Ducati is fitted with a very convenient and easy to operate "rock-back" stand, and that was fine, but it also had a swinging prop that would have also been fine except for one small detail: it extends down and outward far enough to "ground" every time the machine was banked over very far in a left turn. This was particularly outrageous in view of the fact that the Ducati will corner so well. After removing the stand, we could drop over in a bend until the pegs were about to drag (you "feel" the pavement with the side of your boot-sole to make certain things do not go too far).

For all around sports/touring/racing use, it would be hard to find a better bike than the Ducati. Its finish is marvelous, it is quite fast, and it handles in a way that few others can match. Also, it is so smooth that one begins to wonder if there is any point in building twins (we know there is, but not for reasons of smoothness) and we have had good reports of its durability. The makers offer the machine in several forms — depending on the use for which it is intended — and they have just come up with a super-tuning kit (consisting of a cam and spe cial piston) for those who like that sort of thing. Try the Ducati and you will like it; we did. •

DUCATI MONZA

SPECI FICATIONS

$579.00

PER FORMANCE