International Six Days Trial

IT TAKES six cross-country bike men of very special caliber, all riding to the limit on virtually unbreakable motorcycles with a turn of speed to boot — and extra doses of luck — to win the International Six Days Trial. But none of them are working any harder than the individual riders, club team members, factory team men, or Silver Vase contestants for that matter. This is the big leagues, whether you ride for the national trophy team or as the only entrant on the list from your country.

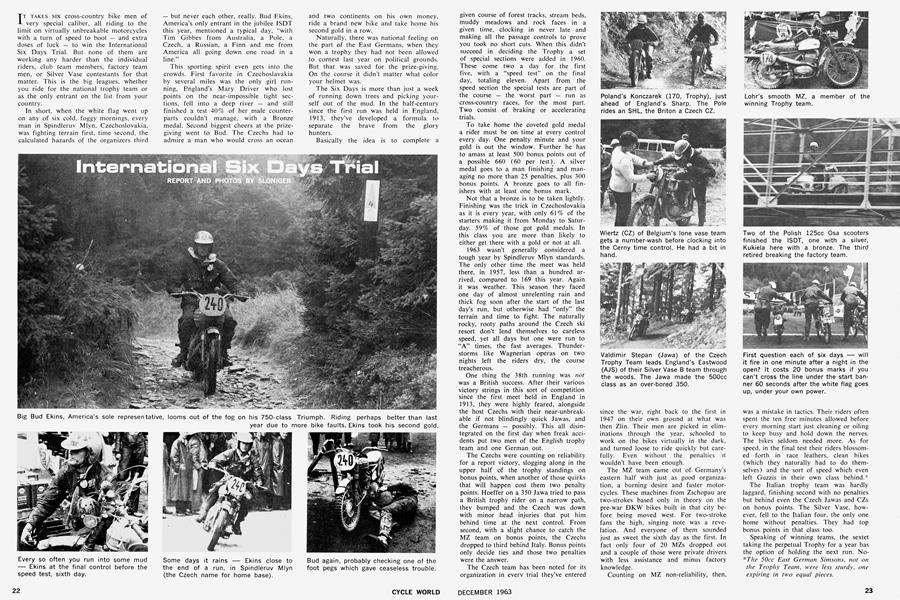

In short, when the white flag went up on any of six cold, foggy mornings, every man in Spindleruv Mlyn, Czechoslovakia, was fighting terrain first, time second, the calculated hazards of the organizers third — but never each other, really. Bud Ekins, America’s only entrant in the jubilee ISDT this year, mentioned a typical day, “with Tim Gibbes from Australia, a Pole, a Czech, a Russian, a Finn and me from America all going down one road in a line.”

This sporting spirit even gets into the crowds. First favorite in Czechoslavakia by several miles was the only girl running, England’s Mary Driver who lost points on the near-impossible tight sections, fell into a deep river — and still finished a test 40% of her male counterparts couldn’t manage, with a Bronze medal. Second biggest cheers at the prizegiving went to Bud. The Czechs had to admire a man who would cross an ocean and two continents on his own money, ride a brand new bike and take home his second gold in a row.

Naturally, there was national feeling on the part of the East Germans, when they won a trophy they had not been allowed to contest last year on political grounds. But that was saved for the prize-giving. On the course it didn’t matter what color your helmet was.

The Six Days is more than just a week of running down trees and picking yourself out of the mud. In the half-century since the first run was held in England, 1913, they’ve developed a formula to separate the brave from the glory hunters.

Basically the idea is to complete a given course of forest tracks, stream beds, muddy meadows and rock faces in a given time, clocking in never late and making all the passage controls to prove you took no short cuts. When this didn’t succeed in deciding the Trophy a set of special sections were added in 1960. These come two a day for the first five, with a “speed test” on the final day, totaling eleven. Apart from the speed section the special tests are part of the course — the worst part — run as cross-country races, for the most part. Two consist of braking or accelerating trials.

To take home the coveted gold medal a rider must be on time at every control every day. One penalty minute and your gold is out the window. Further he has to amass at least 500 bonus points out of a possible 660 (60 per test). A silver medal goes to a man finishing’ and managing no more than 25 penalties, plus 300 bonus points. A bronze goes to all finishers with at least one bonus mark.

Not that a bronze is to be taken lightly. Finishing was the trick in Czechoslovakia as it is every year, with only 61% of the starters making it from Monday to Saturday. 59% of those got gold medals. In this class you are more than likely to either get there with a gold or not at all.

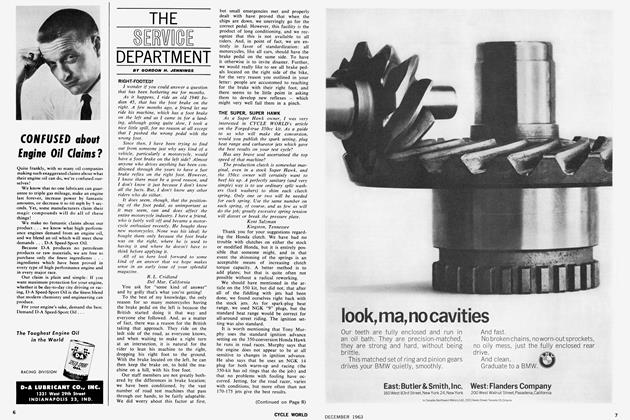

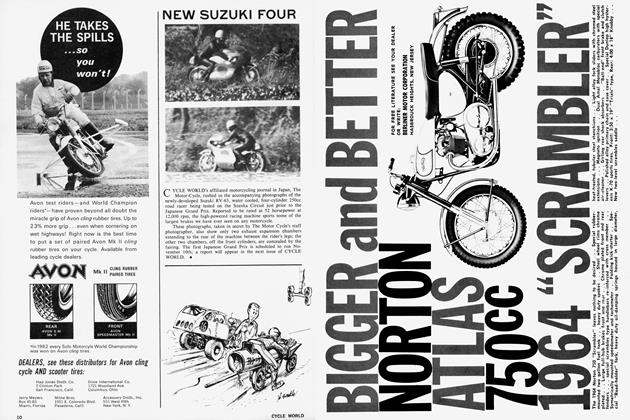

1963 wasn’t generally considered a tough year by Spindleruv Mlyn standards. The only other time the meet was held there, in 1957, less than a hundred arrived, compared to 169 this year. Again it was weather. This season they faced one day of almost unrelenting rain and thick fog soon after the start of the last day’s run, but otherwise had “only” the terrain and time to fight. The naturally rocky, rooty paths around the Czech ski resort don’t lend themselves to careless speed, yet all days but one were run to “A” times, the fast averages. Thunderstorms like Wagnerian operas on two nights left the riders dry, the course treacherous.

One thing the 38th running was not was a British success. After their various victory strings in this sort of competition since the first meet held in England in 1913, they were highly feared, alongside the host Czechs with their near-unbreakable if not blindingly quick Jawas, and the Germans — possibly. This all disintegrated on the first day when freak accidents put two men of the English trophy team and one German out.

The Czechs were counting on reliability for a report victory, slogging along in the upper half of the trophy standings on bonus points, when another of those quirks that will happen cost them two penalty points. Hoeffer on a 350 Jawa tried to pass a British trophy rider on a narrow path, they bumped and the Czech was down with minor head injuries that put him behind time at the next control. From second, with a slight chance to catch the MZ team on bonus points, the Czechs dropped to third behind Italy. Bonus points only decide ties and those two penalties were the answer.

The Czech team has been noted for its organization in everv trial they’ve entered since the war, right back to the first in 1947 on their own ground at what was then Zlin. Their men are picked in eliminations through the year, schooled to work on the bikes virtually in the dark, and turned loose to ride quickly but carefully. Even without the penalties it wouldn’t have been enough.

The MZ team came out ofGermany’s eastern half with just as good organization, a burning desire and faster motorcycles. These machines from Zschopau are two-strokes based only in theory on the pre-war DKW bikes built in that city before being moved west. For two-stroke fans the high, singing note was a revelation. And everyone of them sounded just as sweet the sixth day as the first. In fact only four of 20 MZs dropped out and a couple of those were private drivers with less assistance and minus factory knowledge.

Counting on MZ non-reliability, then, was a mistake in tactics. Their riders often spent the ten free minutes allowed before every morning start just cleaning or oiling to keep busy and hold down the nerves. The bikes seldom needed more. As for speed, in the final test their riders blossomed forth in race leathers, clean bikes (which they naturally had to do themselves) and the sort of speed which even left Guzzis in their own class behind.* The Italian trophy team was hardly laggard, finishing second with no penalties but behind even the Czech Jawas and CZs on bonus points. The Silver Vase, however, fell to the Italian four, the only one home without penalties. They had top bonus points in that class too.

Speaking of winning teams, the sextet taking the perpetual Trophy for a year has the option of holding the next run. No*The 50cc East German Simsons, not on the Trophy Team, were less sturdy, one expiring in two equal pieces.

body can say the East Germans weren’t confident since their FIM rep was already authorized to announce Saturday night, a few hours after the final test, that his government had filed the regular request with FIM headquarters in Geneva to hold the 1964 trial in Thuringia.

For many private riders, and even a few teams with less than perfect management, the trial was indicated if not decided in the first section of the first day. The Czech organizers — who incidentally managed the mass of 280 riders and all the side issues with exemplary smoothness — had inserted a “hook” which went unnoticed by many. The very first section was not only difficult but it was short. You can make up a minute lost in a 25mile leg, but it’s hard to win back half that in only three or four miles to the first clock. Most of these old hands made this leg, then blasted into orbit trying to keep well ahead of what seemed a nearimpossible schedule for the rest of the day. On the really rocky portions they simply beat their bikes to pieces.

Thoughtful types realized that the legs were longer thereafter and took it easier. Rocks and roots made the running this year, more than water splashes or sandy leaps. There was very little “road” used, even of the gravel type, with the bikes jarring over sharp, jolting stone lips for most of the 983 miles. When the rocks and roots weren’t rough they were just lightly moist, (i.e. slipperier than hell with an invisible coat of slime).

This caught Mary Driver out on the last day when her 250cc Greeves simply slid out from under her on a narrow, cause-way-like path. Fortunately the machine stayed on the ridge while the poor rider, driving suit and all, tumbled down the side and into a river deep enough for her to go clear under a couple of times before finding footing and clambering up to the path again. She reckons soaking clothes are not the warmest way to rush about Czechoslovakia on a motorcycle but continued, gaining only 13 points for the day on the tightest of “A” times.

Saturday was a tight day for everybody. Again the first section was short, tight and with wet rocks. Bud arrived at the clock already into his safety minute and knocked over the time-keeper’s table getting his route card into the printing clock. Tim Gibbes, an old Ekiris pal from Australia, riding for the British Trophy Team, was even later after having missed the start. He landed almost on top of Bud and still made it. Seems nobody told Tim his group (riders go off in bunches of four, a minute apart) was on the line.

A late start can’t cost you penalties under the current rules, as it once did, but you lose 20 bonus points if you aren’t over the second line one minute after the flag goes up, under engine power. Also you lose time on a tight section naturally. Ekins also lost twenty, on the fourth day, when he couldn’t get ready in ten minutes. The motorcycles stand in the open all night, with only those ten minutes to make it ready next morning, apart from what time you stole from the last leg the night before, since the last time check is the entrance to the parc ferme.

Bud was working under the handicap of starting on a motorcycle with less than 100 miles on its clock (as he did last year), and one to boot with a couple of experimental features he hadn’t known would be there until collecting the bike in England a few days before the meet. A gold is worth center position on the mantle from any Six Days but Ekins probably worked harder and rode against greater odds by far this year for his gold than in Garmisch last season.

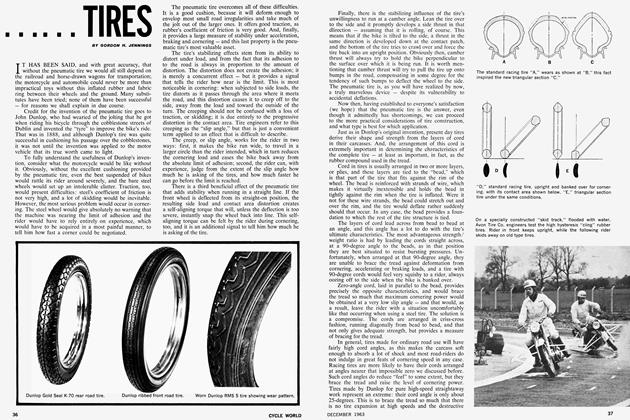

In ’62 the Ekins big Triumph (750 class) was starting first kick on the coldest day and running easy, apart from when he dropped it playing racer with Gibbes on the gravel curves. This year the foot pegs were too long and Bud lost points even on speed sections gathering them up again to remount. His “bolt pocket” was getting pretty low by Saturday, the total going into the foot pegs. Riding a special section on one leg isn’t easy either.

Worse, for a rough track, the front fork springs had been re-designed and promptly collapsed on Monday. For very nearly the whole six days Ekins was fighting a motorcycle with no give at all in the front end over one of the bumpiest courses many ISDT regulars could remember. He wasn’t alone, incidentally. A lot of springs gave up, but most of the riders weren’t on the big bikes, pushing for the highest set averages of all. The upper divisions had to average 28.6 mph, to stay clean.

One Czech team man came back with an expression of pure awe on his face the first day, reporting that Bud started a muddy hill 50 yards behind him, “and passed me before I got to the top - going sideways!”

Bud dropped off the pace in the speed test for that very reason — going sideways. As Gibbes said, “he got into some pretty hairy slides round back. Anybody but Bud, I’d been worried.” Seems, along with his other troubles, Ekins was suffering from a loose rear spindle, “so that the rear wheel steered every damn time I lay it over.” As an example of the ingenuity which wins gold medals, Bud rigged his crankcase breather to make a drip oiler for the rear bearing which was giving every sign of seizing momentarily the final day. The spare oil on the. rear tire was no special embarrassment in the mud but something of a sled ride on the asphalt of the speed test.

Rocket of the speed test — and all the other special tests for that matter — was Germany’s only big-bike man, Sebastian Nachtmann on his special BMW R-69. With carburetors sticking out both sides you wouldn’t call the boxer twin an ideal bike for rutted paths but Nachtmann just stands on his pegs rocking first one than the other cylinder over the high spots.

Special tests are scored by averaging the times of the three fastest men in a class and making that bogey time for a perfect 60 points. The rest get a percentage of that and Nachtmann had a “perfect” 660 for eleven tests in a class where only Bud and an Englishman weren’t riding for a Trophy team, supposedly the best. Nachtmann incidentally, is guide man for the German team.

Bud finished with 619.6 points (having lost 20 on that one start) only threefourths of a point out of the class second, behind Nachtmann and Gibbes. Even with the 20 docked he ran in the top fifth overall among the finishers, in the only class with 100% scored.

You finish in this kind of company riding with your head, and hoping the repairs come on the easier legs. There weren’t any “easy” sections but some were too tight for so even as little as a cable replacement. Bud Ekins doesn’t relish changing tires or anything else unnecessary, “might pinch a tube.” Actually he works on the theory of not monkeying with a part that’s running well. He went through this year again on one set of tires, getting the knobs worn off nicely before the speed test on asphalt, one set of plugs, and two chains, changing the fifth morning just to be safe, not because it broke.

An American team some day? He thinks it’s possible, claiming any number of US riders could outride him, just from his own area of the country alone (California). You’ll never convince the Czech journalists of that. One admitted to us he was skeptical of this tall American who looked so easy off the start. — until he saw him pass the best of them in the rough stuff with no “cowboy.” That style, and proper bikes, would decide the possibility of an American team. Judging from the interest one man in a whitestriped blue helmet sparked, it would be worth trying, on a base level at least where you only need four men, riding bikes of any manufacture they like (all Trophy Team machines however must be made in the country entering them).

It takes luck to win the Six Days, no matter how good your team is, but the riders with the gold medals, 102 of them in Spindleruv Mlyn, are the kind who make their own luck — most of the time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue