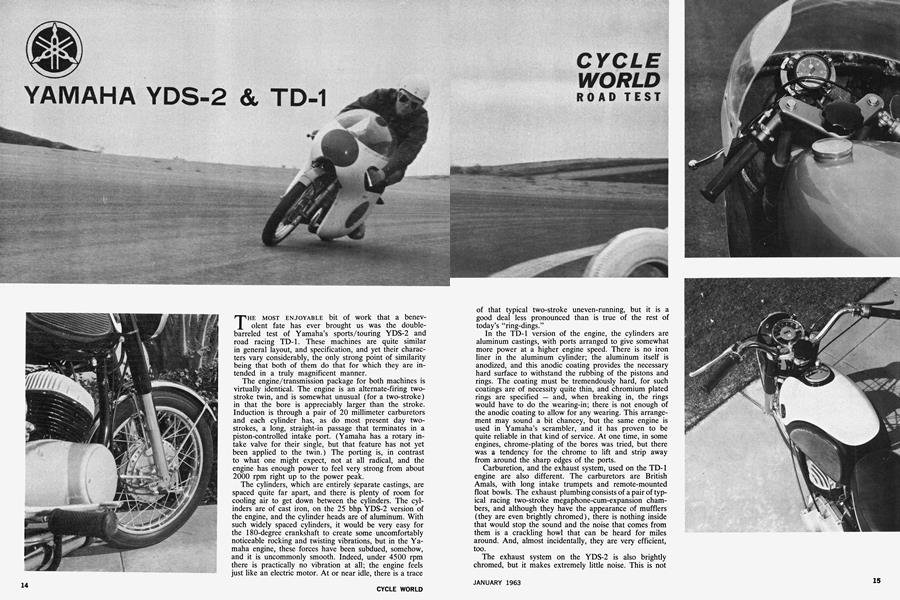

YAMAHA YDS-2 & TD-1

THE MOST ENJOYABLE bit of work that a benevolent fate has ever brought us was the doublebarreled test of Yamaha’s sports/touring YDS-2 and road racing TD-1. These machines are quite similar in general layout, and specification, and yet their characters vary considerably, the only strong point of similarity being that both of them do that for which they are intended in a truly magnificent manner.

The engine/transmission package for both machines is virtually identical. The engine is an alternate-firing twostroke twin, and is somewhat unusual (for a two-stroke) in that the bore is appreciably larger than the stroke. Induction is through a pair of 20 millimeter carburetors and each cylinder has, as do most present day twostrokes, a long, straight-in passage that terminates in a piston-controlled intake port. (Yamaha has a rotary intake valve for their single, but that feature has not yet been applied to the twin.) The porting is, in contrast to what one might expect, not at all radical, and the engine has enough power to feel very strong from about 2000 rpm right up to the power peak.

The cylinders, which are entirely separate castings, are spaced quite far apart, and there is plenty of room for cooling air to get down between the cylinders. The cylinders are of cast iron, on the 25 bhp. YDS-2 version of the engine, and the cylinder heads are of aluminum. With such widely spaced cylinders, it would be very easy for the 180-degree crankshaft to create some uncomfortably noticeable rocking and twisting vibrations, but in the Yamaha engine, these forces have been subdued, somehow, and it is uncommonly smooth. Indeed, under 4500 rpm there is practically no vibration at all; the engine feels just like an electric motor. At or near idle, there is a trace

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

of that typical two-stroke uneven-running, but it is a good deal less pronounced than is true of the rest of today’s “ring-dings.”

In the TD-1 version of the engine, the cylinders are aluminum castings, with ports arranged to give somewhat more power at a higher engine speed. There is no iron liner in the aluminum cylinder; the aluminum itself is anodized, and this anodic coating provides the necessary hard surface to withstand the rubbing of the pistons and rings. The coating must be tremendously hard, for such coatings are of necessity quite thin, and chromium plated rings are specified — and, when breaking in, the rings would have to do the wearing-in; there is not enough of the anodic coating to allow for any wearing. This arrangement may sound a bit chancey, but the same engine is used in Yamaha’s scrambler, and it has proven to be quite reliable in that kind of service. At one time, in some engines, chrome-plating of the bores was tried, but there was a tendency for the chrome to lift and strip away from around the sharp edges of the ports.

Carburetion, and the exhaust system, used on the TD-1 engine are also different. The carburetors are British Amals, with long intake trumpets and remote-mounted float bowls. The exhaust plumbing consists of a pair of typical racing two-stroke megaphone-cum-expansion chambers, and although they have the appearance of mufflers (they are even brightly chromed), there is nothing inside that would stop the sound and the noise that comes from them is a crackling howl that can be heard for miles around. And, almost incidentally, they are very efficient, too.

The exhaust system on the YDS-2 is also brightly chromed, but it makes extremely little noise. This is not

to say that the machine is completely silent; the air cleaners used on the bike are efficient in their primary purpose, but they don’t stop the noise from the hammering of air inside the induction tract, and when full throttle is applied, the YDS-2 really makes its presence known. Actually though, we can’t complain about this; it is, to our ears anyway, a delightful noise and the bike gains something for having it.

With the increases in power output, relative to the YDS-1, there have been some changes in crankcase and primary drive. There has been some reinforcing of the former, which is not interchangeable with earlier models, and the latter, the primary drive, has been redesigned altogether. The primary reduction, previously 2.50:1, is now 3.25:1, which gives slower-running transmission gears, with attendant reductions in transmission losses. Also, the shock-cushioning hub incorporated in the drive has been redesigned for smoother action and the added capacity needed for the extra power.

In the vanguard of a trend that will, we think, eventually become much stronger, the Yamaha YDS-2 (and, of course, the TD-1 road racer) has a five-speed transmission. Its gears are carried in an extension that is integral with the crankcase, and all ratios are indirect, the drive coming in on one shaft, from the clutch, passing across one of the five sets of gears to a secondary shaft, and finally emerging out the opposite side of the case at the drive sprocket. Gear engagement is done through dogs, and due to the slow (the 3.25:1 primary reduction helps here) rotation of the gears, there is never a trace of snatching or noise when the dogs mesh. Also, the unusually close spacing of the ratios helps make the engagement smooth.

If this Yamaha transmission has any faults, we were unable to find them. We had not been aware that the similar unit used in the YDS-1 had given any trouble, yet this new transmission has been strengthened — perhaps just in anticipation of obscure ailments that might be caused by the increase in power. The only flaw, and we are not entirely sure that it was a flaw, was the fact

that the extra speed has crowded out Yamaha’s customary electric starter. The end-of-the-crank positioning of generator, etc., makes the Yamaha’s crankcase very wide, and they did not wish to widen it even further to get in an electric starter.

As our experiences with the YDS-2 proved, the electric starter is not really necessary. This machine will come to life, even after it has been setting idle for several days, with only two kicks: the first kick is needed to get the cylinders primed; ’the second gets it running. No tickling of floats is needed, or any fiddling with air-control levers; however, there is a small lever that lifts a pair of valves in the sides of the carburetors, admitting an extra-rich mixture for cold starting, which is all that is needed under any but the most extraordinary circumstances.

Both the YDS-2 and the TD-1 have two-loop tubular steel frames — the one for the road racer being made of lighter-gauge material. The front and rear suspensions, telescopic forks and swing arms, are also the same for both, but the TD-1 is much stiffer sprung and damped. The YDS-2 has a very “touring” ride — just verging on being spongy, in fact, and both bikes are extremely stable at any speed. The springs on the YDS-2 are enclosed, and we could not tell if it had a setup similar to the TD-1, which had the lower coils on its springs closer together than those above, to allow part of the coils to “bottom” first, and thereby provide a progressive spring rate.

The brakes on the YDS-2 are very large; those on the TD-1 are enormous. In both instances the front brakes have two leading shoes, with single leading shoes (one leading, one trailing) for the rear brakes. The drums are of light alloy, with iron liners, and they give most impressive stopping power to both bikes. The backing plates on the road-racer had cast-on air scoops, and the backs of the drums are perforated to allow the warm air a path for escape. The brakes of the YDS-2, intended more for touring, are closed and, as nearly as is possible, sealed. This is to prevent dust and, when it rains, water from getting in on the linings. With proper regard for the hard use even the touring-bike brakes are likely to receive,

Yamaha has specified a rather hard brake lining that does not change its frictional properties much even when very warm. The brakes on the road bike were outstanding for being powerful, of course, and they were also noteworthy for their smoothness. At no time did we experience any of the shuddering that can develop when brakes are used hard. The brakes on the road racer were even more powerful, just as smooth, and required little more pressure at the controls to produce the same level of stopping power.

For instrumentation, the YDS-2 had a tachometer and speedometer mounted up in the headlight fairing. They are neatly and tastefully arranged, but the tachometer reads far beyond the speed that the engine will actually attain, with the result that the slice of the scale that is used is squeezed down too much. And, on our test bike, the speedometer was a bit sticky, which made it impossible for us to calibrate it properly. The accuracy did, however, seem to be pretty good. The largest error recorded in our check-out procedure was only a bit over 2 mph (at 70 mph), but the needle always drags behind the true speed a bit and makes an actual tabulation, like we usually present, impossible.

Seating and controls were, for the most part, really marvelous. The TD-1 is a trifle crowded for an over-sixfoot rider and the grab-strap over the seat on the YDS-2 was badly placed (it caught most of us right under the point of contact) but the location of the bars and pegs couldn’t have been better.

To gather riding experience on both bikes, we made one of our frequent pilgrimages to Riverside Raceway to try the machines on a road circuit. There, we learned some very enlightening things. The road racer proved to be a far more tractable and comfortable machine than we had presumed, and the YDS-2 touring bike exhibited signs of being entirely too fast for its, or our, good. For normal touring, the YDS-2’s handling was marvelous, but when it is pressed hard, as it was that day at Riverside, the suspension is far too soft for what is being demanded of it. Traveling at about 85 mph down through a series of “esses,” the YDS-2 would (when heeled over and cornering hard) surge up and down on its suspension and it became a bit hard to hold on the proper line. True, this is behavior that would never come to light in the kind of use the bike would get from the average rider, but it is not an average bike, and we suspect that most

of the people who would buy it would, at some time, ride it like we did. We finally quit pressing our luck with the YDS-2 when the Technical Editor (who was having a hammer-and-tongs race with the Advertising Manager, riding the TD-1) got the YDS-2 heeled way over, caught the shift lever on the pavement and bent it back around the foot peg — all without dropping the bike. From all this, we concluded that with a slightly stiffer suspension, the YDS-2 would be one of the best, but that, as is, it is too soft for anything but touring. Certainly, even with the soft suspension, the steering and stability are of the highest order.

The TD-1 was, with its good firm suspension, just what the YDS-2 could have been. It would corner far faster than any of us would press it, and its engine was a lot stronger than any 250 we have tried recently. The gearing on this particular machine was set up for the Isle of Man race, and it was drastically overgeared for Riverside. In fact, the engine would only pull 7500 rpm in 5th cog, and that is well below its peaking soeed of 8500 rpm. Given the proper gearing, the TD-1 should be capable of 113-115 mph, and perhaps a bit more.

Through the intermediate (for a racing bike) speed range, the TD-1 was much better for the relatively inexperienced road-racer than most of the similar machines we have tried. It has a lot of power over a fairly wide range of engine speed, and the 5-speed transmission gives one a gear for every occasion. Curiously, the gear ratios (identical with those of the YDS-2) which had seemed so nice and close on the touring bike felt a bit widely spaced on the TD-1. This is probably due to the slightly narrower spread of power in the hotter version of the engine.

After testing at Riverside, we hauled both bikes to our favorite drag strip, the strip run by the Long Beach (Calif.) Lions Club, and did our acceleration runs. Much to our surprise, the TD-1 went fast enough to carry the editor off to a trophy in the 15-cubic inch gas class. And that was done, mind you, pulling the tall Isle of Man gearing. We may go back with drag strip gears and try it again some time. On another occasion, ridden by Skip Clark, Sales Manager of Yamaha Inti., the TD-1 turned a smart 94 mph at the same strip using lower gearing.

The YDS-2 was a pleasant surprise too. The engine is not “big-inch,” or anything like it, but the bike comes off the line like a shot, and although it begins to fade a bit as it approaches 70 mph, the elapsed time for the standing-start 1/4-mile puts it right up there with some very peppy machines. And, down in the speed range where most riding is done, the YDS-2 will give a lot of 15-cubic inch bikes a lot of trouble.

Both of Yamaha’s bikes were particularly well finished: the road racer neatly, but without much flash; the YDS-2 just as neatly, or more so, and with a great deal of elegance even down at the level of small detail. The bike simply looks, and is, designed, styled, and put together just right. There are no shabby details; no place where excellence of finish has been made subordinate to the time demands of an assembly line. The YDS-2 is, by and large, the best finished 15-incher we have ever seen, and it ranks very high on our list of nicely-finished bikes we have seen — and that includes certain highly regarded German and British “classics.”

As one might gather from this report, all of us liked the Yamahas enormously and we were sorry to see them returned to the distributor. The sheer sporting fun delivered by the TD-1, and the pleasant smoothness and sparkling performance of the YDS-2, have created — not only among our staff members, but also with the incidental people who saw the two bikes at the drag-strip — a lot of respect for Yamaha and their products. •

YAMAHA

YDS-2 & TD-1

$599 & NSA.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

January 1963 By Joseph C. Parkhurst -

The Service Department

January 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings -

Cylinders: Single, Twin Or Multi?

January 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings -

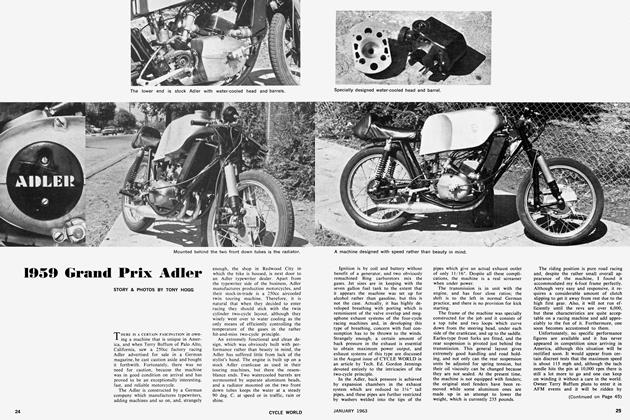

1959 Grand Prix Adler

January 1963 By Tony Hogg -

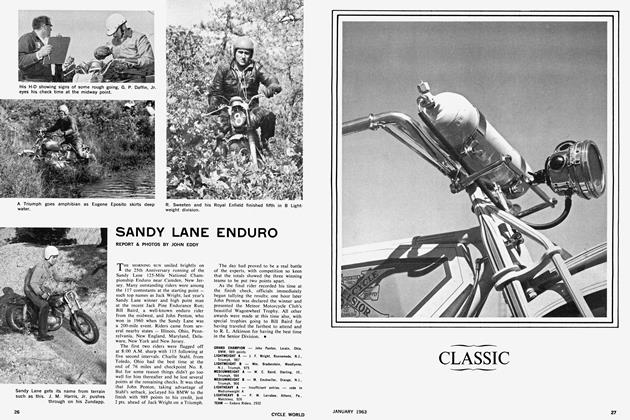

Sandy Lane Enduro

January 1963 By John Eddy -

A Cycle World Classic: 1914 Excelsior

January 1963 By Paul A. Bigsby