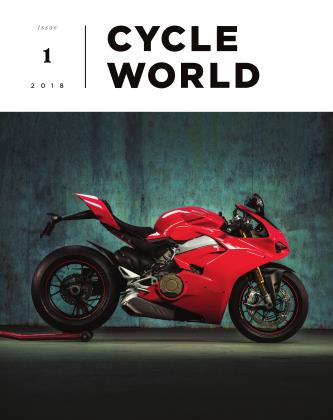

Testing Ducati’s new breed of superbike

January 2 2018 Zack CourtsTHE KING IS DEAD, LONG LIVE THE KING

Testing Ducati’s new breed of superbike

ZACK COURTS

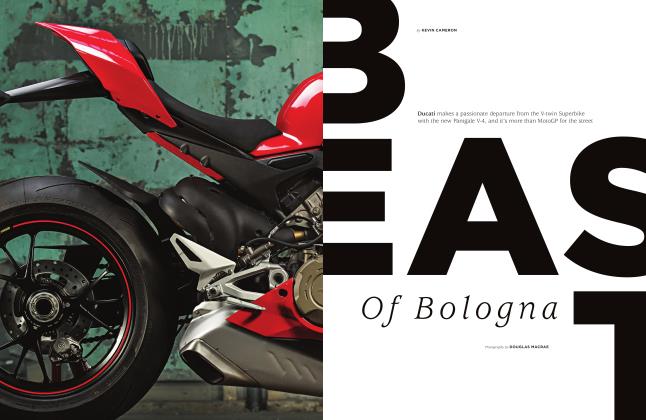

When Ducati management stood up and proclaimed that the new Panigale V-4 was the “closest bike in the segment to a MotoGP machine,” there were probably a few sets of eyes rolling around the room. This is common rhetoric from Ducati—to lean on racing lineage and how it resides in the passion the company delivers to the public. It taps into our basic, adolescent instincts about motorcycles: the more power, the bigger the brakes, the louder the exhaust, the better. I know the feeling well. I was a child once.

What I learned about Ducati’s hunger for racing, however, by slinging my inner child around the Circuit Ricardo Tormo near Valencia, Spain, was not what I was expecting. It wasn’t about passion at all, or history, or trophies. Ducati found a way to transmit a new kind of performance in its superbike. A new flavor of strength that I think was developed on the world stage and isn’t in any of the teaser videos or brochures.

Some might argue that the new flavor is evident as soon as the engine turns over and hres. Instead of the laborious cranking of two huge pistons, the Panigale V-4 starter motor taps its toes quickly to jump the twin-pulse engine into a typical, lumpy, Ducati idle. And really, it’s much more typical than you would think. Plenty of people will think it’s a twin the first time they hear it run in person. From the saddle, it’s quick to rev, and there’s more than a hint of performance in the raspy notes belching out of the underslung pipe. Like it wants to go fast.

Instead, I trundled down pit lane toward the circuit at a few thousand rpm in third gear and soaked up the basic feel of the bike. The dash is modern and fairly dazzling, as you would expect, yet in some ways much more traditional than Panigales of the past. The all-digital screen is taken up by an analog-style tachometer on the right, with menus and data scattered around the rest of the display. It’s complicated, with a touch of class.

The ergonomics are much more like the outgoing 1299 than I expected: lithe and compact, with an aggressive reach forward to the wide bars. While previous Panigales had noticeably more legroom than other superbikes, the V-4’s footpegs are 10mm higher, which makes it feel a little more conventional. More appropriate, even. It’s still narrow too, despite the “Desmosedici Stradale” engine being 1.7 inches wider than the 1299 mill.

A few laps of warming up to the new engine was all it took. It’s intuitive, linear, and easy to use, which is more than could be said about the 1199 and 1299 Superquadro powerplants. Plus, the addictive midrange punch now leads to a 14,500 rpm rev limit instead of the fun ending a few thousand rpm earlier. The l,103cc engine being 10 percent larger than any other bike in the class doesn’t hurt, and because it’s bigger, it will surely set a new bar for power in the category. Ironically, the more I tried to experiment with the cosmic power of the engine, the more I became transfixed by the handling.

Soon, I was leaning hard on the V-4’s tires and making the chassis work. The traction-control light was illuminating on corner exits, and even though I was going faster every lap, I wasn’t missing any marks. I felt a rhythm forming—something that happens only when the bike is working with you and not against you. It was brilliant, and nearly everything I couldn’t do on a 1299. I went faster into corners and threw the bike from side to side more violently until I started to run out of energy.

I tried my best to override the bike, to get it to break its poise and unleash a feral beast, but it never did. It simply delivered more and more performance, in exactly the quantities that I requested, until I had to tap out. The radiator fan humming and the ripped-up rubber on the edge of the tires were the only signs the bike had humored me.

This isn’t a huge surprise in this age of sportbike capability, but it does represent a massive step forward for Ducati.

Dismantling this clinical display of speed that the Panigale V-4 had delivered to me is possible only with all of the secrets that Ducati laid into the motorcycle. We don’t have the whole recipe, but we know enough to decipher how the company transformed its flagship superbike from a manic-depressive rocket ship to an even-keeled superbike on the cutting edge of the industry. From my perspective, it all goes back to cohesion.

Ducati first went racing with a V-4 engine in the MotoGP World Championship in 2003, and historically it has been about two things: speed and tradition. In the early days, there was a steel-trellis frame, 200-something horsepower, and very little finesse to be seen with the naked eye. Riders wrestled vicious machines around the tracks, sometimes smoking tires to a pulp or breaking delicate pieces with sheer velocity. Ducati had some success with the hre-and-brimstone method, winning races and even a championship. By 2010 the MotoGP machine was the epitome of light and fast and difficult to ride.

Much of that seemed to be transmitted to the Panigale superbike. It was often 15, 20, or even 30 pounds lighter than the competition, with just as much power, more electronic options, and all of the best components. But it was unforgiving to ride, especially on a racetrack. The engine was peaky and hard to manage, the electronics seemed a step behind, and the chassis flexed in a way that mere mortals struggled to control.

Early sketches of the V-4 showed the shock mounted on the side, a la 1199 and 1299 Panigales. But for production, it’s tucked in between the engine and rear wheel, like most motorcycles. When I asked the designer, Julien Clement, he told me the side-mounted shock was getting in the way of the test rider, so they moved it. He even said he proposed a system to pull on the shock instead of push, but it was “too technically difficult to realize and with no real benefit.” So it began: a whiff of pragmatism.

Over the past 15 years, MotoGP has become more about control than power. Ducati’s approach in the past few years (certainly in the timeline of the development of the V-4) has followed suit. The team has adopted an aluminum frame, for one, much more similar to conventional bikes. The machine has become more consistent and reliably at the front of the pack. Even still, it was reported that Ducati riders were especially tired at the end of a race.

On the Panigale V-4 at Valencia, so much of the precision and ease of use seemed to come from the bike’s ability to change direction and hold a line. Compared with a 1299, it felt like it was on tires half the width or was 25 pounds lighter. It seemed the backward-rotating crankshaft was making a difference, canceling out some of the inertial mass of the spinning wheels, rotors, and tires. “Every team in MotoGP has a counter-rotating crank,” Kevin Cameron explained when I asked about it, “and do you think they do that because it’s fashionable?” No sir, I do not.

Unless speed is fashionable. Then you could argue that it’s sexy to take advantage of the engine’s dimensions to stretch the swingarm and extend the wheelbase by 1.25 inches.

Or to refine the front-rear weight distribution. Or shape the fuel tank so it runs back under the seat, keeping weight as low as possible. The engine is still a stressed member of the chassis, but now there’s a frame to connect the rider’s seat to the rest of the bike. It’s not flashy stuff, but it matters.

Last, the impossibly complex network of electronic rider assists. The highest number or most advanced isn’t the story here, but rather how they work together. Up to this point, Ducati’s electronic systems really have been useful only in saving the rider from a catastrophic mistake. Now, the Panigale V-4 electronics have been refined to within a millimeter of the state of the art. Traction control, wheelie control, slide control, ABS, engine-braking, and yes, even the steering damper, are adjustable and work so well together that you could forget the menus are there. Which is the whole point.

On the Ohlins-equipped S version that I rode, the NIX30 fork and TTX36 shock read and adjusted the compression and rebound damping as I rode, as often as 100 times every second. It is miraculous, extraordinary technology that I turned off and could barely tell the difference. In part because MotoGP tracks are smooth, but also because even though the system made changes as large as 50 percent of the range of adjustment while I rode, it did so covertly. Plus, let’s be honest, that many thousands of dollars in suspension is bound to work pretty well, even when the settings are static.

As amazing as the electronic suspension is, you could argue it’s a gimmick. Same goes for the huge, beautiful dash. The suspension also comes at some cost, incidentally, with the midline S version (which Ducati expects to be the main seller) priced at $27,495. Forgoing the forged wheels and electronic Ohlins for the Showaand Sachsequipped base model will add 2 pounds of weight total and save $6,300, ringing in at $21,195.

They are differently equipped, and while I haven’t ridden the base bike, I think any version of the Panigale V-4 cradles deep in its core the most important value attained in MotoGP competition: precision. This new machine is the most powerful Ducati superbike I’ve ever ridden, but that’s not why it’s the most impressive. If anything, MotoGP learned about emotion from Bologna. The lesson Ducati learned from MotoGP is one of cohesion. Focusing all of that passion in the right direction at the right time—that’s what defines this new superbike horizon.