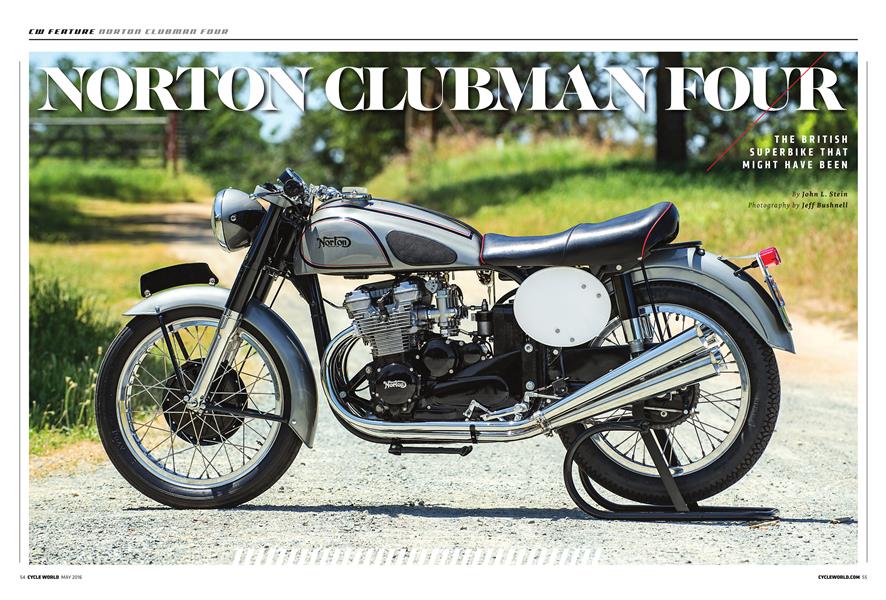

NORTON CLUBMAN FOUR

CW FEATURE

THE BRITISH SUPERBIKE THAT MIGHT HAVE BEEN

John L. Stein

If the devil lives in the details, this Yamaha-powered Norton "Clubman" special built by Northern California's Paul Adams must be totally possessed. Exquisitely crafted with various leftover parts from 1950s and ’60s Nortons that Adams had restored over the years—plus a 1985 Yamaha FJ600 engine found at a motorcycle wrecker—it quite literally represents what the storied English firm might have built if it had not fallen on hard times 60 years ago.

As evidenced in the 1962 book Built for Speed by John Griffith, during the 1950s Norton’s racing department had absolutely designed a 500CC liquid-cooled transverse-four DOHC engine to power its Grand Prix bikes, a clear response to Güera and MV Agusta competition.

Five years in the making, Adams’ street version of the intended racer is nothing less than internal-combustion Britbilce devil porn. “For years, I had huge piles of leftover Norton parts in my attic,” he says. “The main frame is from a 1956 Model 99 twin, and the rear section is all that remains from the frame of a 1962 Manx 350 that I crashed at the Isle of Man. The tank is from a 1954 Dominator Deluxe, the fork and front wheel hub are from a Featherbed International, and the modified rear hub is Commando.” The rims are Borrani, as fitted to Manx racers.

In creating this hybrid, Adams’ first challenge was positioning the relatively compact Yamaha engine in the cavernous chassis opening. That settled, he grafted on suitable engine mounts while also adding brackets for a gel battery and electronics box that mimicked a Norton oil tank.

Hand-bent exhaust headers sweep forward in a graceful arc reminiscent of the Güera GP bikes of the day and merge into baffled megaphones at the rear. Replacing the Yamaha’s bank of Mikuni carburetors with i-inch Amal 276s required scratchbuilding manifolds, a hollow fuel rail, and four intricate throttle bell cranks.

Crowning touches include unique Norton-badged engine covers that Adams had sand-cast at a local foundry and a crossover linkage that converts the Yamaha’s left-side gearshift into a proper English right-side, up-for-first gear pattern. Exceptional finishes also define the Clubman, with Adams duplicating as closely as possible the paintwork, fasteners, and plating that Norton works bikes used. He also finished the engine in a gloss black reminiscent of a Black Shadow’s stove enamel.

ADAMS’ STREET VERSION OF THE INTENDED RACER IS NOTHING LESS THAN INTERNALCOMBUSTION BRITBIKE DEVIL PORN.

Adams offered Cycle World the first long ride on the Clubman in the Gold Country foothills. All period switch gear, controls, and even a Smiths chronométrie speedometer make operating the bike less intuitive than the FJ600 that donated its engine. There is no enricher circuit, so the carbs’ remote float bowl must be flooded manually. Then a vintage chromed handlebar button actives the starter solenoid and the engine cranks over with a high-pitched giggle. Chuffing open carburetor bell-mouths and a tenor note from the exhausts immediately drown the engine’s mechanical noises.

Dynamically, the Clubman is an intriguing blend of classic English and more modern Japanese characteristics. The cable-operated clutch feels typically Japanese, but the right-side gear lever feels like a somewhat stiff English shifter with a much shorter throw. There’s less torque above idle than a typical Brit single or twin has, and the engine grumbles through its lower rev range until it gets onto the cams—right about where an old street single would be signing off. Then the Clubman rockets ahead, a multi-cylinder wail gushing from the four pipes and the Amals sucking air in mad quantities.

A flat handlebar and modestly rearset footpegs, combined with a standard seat height, provide a comfortable and sporty perch. The Featherbed chassis is nicely stable, both in a straight line and while cornering—the very qualities that distinguished Norton from its competitors in the day. That said, the old Roadholder fork and period-looking Hagon shocks don’t approach modern suspension performance, nor do the old-school 19-inch tires. As such, despite its lively power, the Clubman does have vintage dynamic limits, as it would have if it had been produced way back when. But the greatest limit is the 8-inch front and 7-inch rear brakes. To scrub off speed, heave on the levers and then count the seconds as Fate looms closer and closer... Stop please!

But context is everything here, and overall Adams’ creation does look and feel incredibly close to what Norton might have produced for the street if its four-cylinder racer was developed and produced in the 1950s. Had that fledgling project to dominate GP racing worked, motorcycle history might look far different than it does today. But since history doesn’t recognize what-ifs very well, Britbike fans owe Adams a real debt of thanks for building this rolling, breathing, living vision of what might have been.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMaking Things

May 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

May 2016 -

Ignition

IgnitionAlpinestars Tech-Air Race Suit Performance

May 2016 By Bradley Adams -

Ignition

IgnitionFive-Minute Brake the Drill

May 2016 By Nick Ienatsch -

Ignition

IgnitionHoles In the Memory

May 2016 By Paul d’Orléans -

Ignition

IgnitionCreep

May 2016 By Kevin Cameron