THEN AND NOW

IGNITION

TDC

A TALE OF TECHNOLOGIES AND COSTS

KEVIN CAMERON

MotoGP photographer Neil Spalding recently explained that a hat-section round object on the lower left side of Honda RC213V fuel tanks is a means of adjusting fuel tank capacity to allow the mandated maximum of 22 liters to be carried. The “round objects” are made in various heights to allow capacity adjustment.

In 1972, this capacity adjustment was made by placing in the tank various “displacers,” which took the form of 4-ounce and 9-ounce baby bottles. At the time, I chuckled inwardly at the imaginary slogan: “Evenflo—the Baby Bottle of Champions.” We are accustomed to reading that one of the MotoGP constructors will evaluate a new chassis at a post-race Monday test. Presumably the chassis incorporates the latest improvements in specific flexibility, so necessary to corner grip on circuits not recently paved. Or we may see a team hard at work altering steering geometry or weight distribution by installing alternate-offset bearing cups in a bike’s steering head.

Now cast your mind back about 35 years. Kenny Roberts wasn’t getting on with Yamaha’s 0W48 transverse four. Did he and Kel Carruthers wait for Yamaha to release an updated chassis? No. They trucked the thing to Barry Sheene’s shop and sawed the steering head out of the steel frame.

“Where do you want it? That look good?” “A little less. There.”

Once all the tubes were ground to butt closely at the new head angle, Kel tackwelded them in place and then finished the job, welding a bit on the left side then the same bit on the right to minimize distortion.

In 1972, we knew disc brakes were a big improvement on the old cam-and-shoe drum brakes with linoleum linings, but, damn, they were heavy! A front wheel with two of those 0.276-inch-thick stainless 12-inch discs could weigh close to 50 pounds! No wonder

Yvon DuHamel said his Kawasaki H2-R “handled like a lumber wagon”—think of the effort required to steer such a mighty gyroscope! That fall Honda would bring a bike to the Tokyo show with much lighter 5.5mm discs (0.216 inch), but Steve Whiteloclc at Team Hansen had seen Champ cars with brake discs drilled full of holes. He got on the freeway and tooled over to Dan Gurney’s shop, where a pleasing pattern of half-inch holes was soon produced. From that moment came the whole 1970s craze for drilled discs. People at races saw those things on Yvon’s bike and they had to have that look.

Many a home crafter, peering through cutting-oil smoke, pulling the feed handle on his drill press as yet another brand-new half-inch bit screeched its way through the stainless, learned not to use his fingers to clear the jagged, heat-blued chips from the workpiece. Pliers are the right tool.

How do we get lightweight brakes today? Nothing is lighter than carbon discs at four grand apiece, with carbon pads at two grand per set of four. Do you fancy the “made by angels” patina of those i-pound Brembo MotoGP calipers? Yours for $8,500 each. The calipers on the Yamaha TZ750A that it was my privilege to prepare weighed 4.5 pounds apiece.

When we see a modern racebike go leaping and dancing in the gravel, shedding the price of a new car in parts as it whirls, we shall fear no evil, for we know that the wellstocked parts drawers and cabinets in team trucks contain everything needed to restore perfection. We hope the rider fares as well.

But in 1982, when Canadian Miles Baldwin was hurled skyward from his highsiding TZ750, he knew he would come down to face hours at the welding bench, sawing apart his crash-flattened Toomey pipes, restoring their former roundness with hammer and mandrel, and then welding them back together.

BY THE NUMBERS

4-5 THE NUMBER OF TIMES DENSER STEEL IS THAN CARBON-CARBON

$2,600 THE PER-PIECE PRICE OF THE LOVELY TITANIUM FOOTRESTS I SAW FILLING A DRAWER IN A TEAM'S SUPERCROSS TRUCK

$8,500 A POUND THE APPROXIMATE PRICE OF A MOTOGP BIKE (JUST A BIT CHEAPER THAN THE PRICE OF PUTTING IT INTO LOW EARTH ORBIT)

When at the end of 19711 needed a frame for the racebike I was building, I went to see Frank Camillieri, who had a tube bender and a frame jig, and had made several chassis. The frame he built in the next few nights led the Ontario, California, 250-mile AMA 750 national that fall until a few laps from the end, when a connecting-rod bearing welded itself solid. Paul Smart won that day and bought a nice house with the prize money and contingency.

That frame was archaeology because it was made of steel tubing not very different in material or size from the bicycle tubing of the 1890s. If Rex McCandless had seen our frame, he would have recognized the layout he and his brother supplied to Norton for the 1950 TT. Since the first days of the “Safety Bicycle” almost 80 years in the past, motorcycle frames had kept their tight relationship with the bicycle even though by 1972

they were 1,000 times more powerful. No wonder we had the odd wiggle or two.

Antonio Cobas changed that forever in the 1980s with his chassis concept of two large-cross-section aluminum beams. Today, when an ambitious team wants to bust into Moto2, getting a chassis to wrap around the spec Honda CBR600 engine will in round figures cost a hundred grand. And the frame Frank made for me at Christmastime 1971? He thought $300 would cover it. If that’s inflation, then a quart of milk should be $250.

When Yamaha brought out its Grand Prix-inspired RZ500 streetbike in 1984, its production steel exhaust system weighed 42 pounds and kept the rider’s seat nice and warm. When titanium race pipes appeared for Supersport bikes, a complete unit with muffler weighed 7 pounds and was so achingly beautiful that I decided to cease my own miserable pro-

HOWDO WE GET LIGHTWEIGHT BRAKES TODAY? NOTHING IS LIGHTER THAN CARBON DISCS AT FOUR GRAND APIECE, WITH CARBON PADS AT TWO GRAND PER SET OF FOUR.

duction of fitted two-stroke pipes in dreary old mild steel. How y a gonna keep ’em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paris? In 1966,1 paid $80 for a GYT Kit to soup up my dinky YL2-C Yamaha. It contained a big-port rotary valve cover, a disc valve with longer timing, a bigger carburetor, and other engine parts. I was exuberant, returning from Bennington, descending the eastern Berkshires at a sustained 12,000 rpm. Today, what can $80 buy you from the Ducati Accessories Catalog? The battery tender, at $77. All those years ago we dreamed of prototype shops filled with machine tools, of rows of dyno cells containing test engines raging silently behind multiple glass, of technicians at work. Much better than we imagined, it has come to pass and is wonderful to behold. But shucks—only umpteen-billion-dollar corporations can afford it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCommunity

November 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

November 2016 -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Cloverleaf Conundrum Flat-Land Problem: Freeway On- And Off-Ramps

November 2016 By Nick Ienatsch -

Ignition

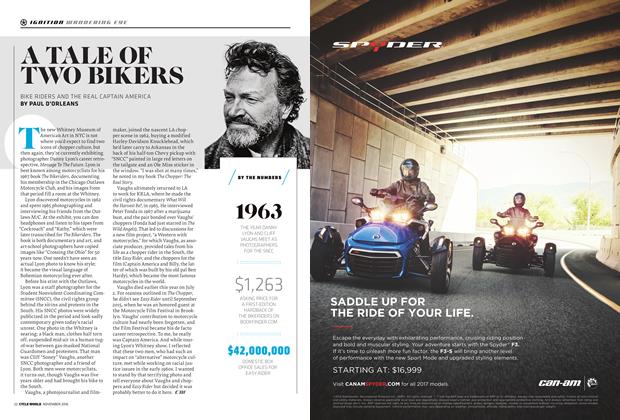

IgnitionA Tale of Two Bikers

November 2016 By Paul d’Orléans -

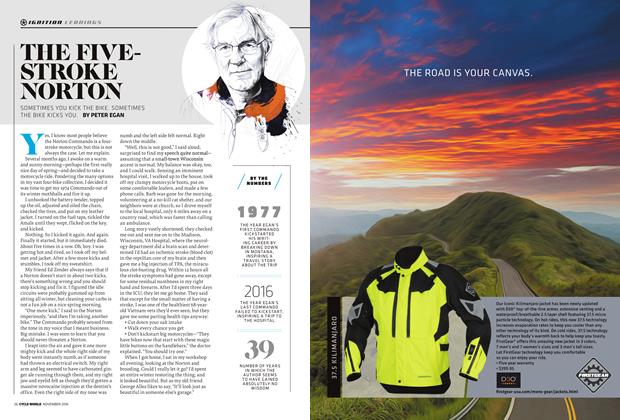

Ignition

IgnitionThe Five-Stroke Norton

November 2016 By Peter Egan -

Cw Tech Preview

Cw Tech PreviewSuzuki's New Sword

November 2016 By Kevin Cameron