RIDERS AND TIRES

IGNITION

TDC

TIRES NEED HEAT, WITHOUT WHICH EVERYTHING FAILS

KEVIN CAMERON

Changes in tires are not only driven by changes in rubber and construction technology but also by what riders need and want from tires.

Back in 2002 at the beginning of MotoGP, Valentino Rossi said this about two-/four-stroke differences relating to tires: “With the four-strokes, there is a close relationship between the throttle and the back tire, so when we accelerate a little we are already giving power to the rear rubber. With the new bike, you can accelerate when you are leaning tightly, which wasn’t the case with the 500, where you had to raise the bike to be able to open the throttle.”

This difference came from the contrasting ways two-strokes and fourstrokes came on throttle. With twostrokes, on closed throttle, the cylinders filled with exhaust, and, as the rider moves the throttle, the small amount of fresh charge is so diluted in the cylinder that it cannot fire. As the throttle opens more and more, this becomes less true. The Honda NSR500 used to give two loud pops (from the ignition of mixture accumulated in the pipes) and then kick the rear wheel sideways as the engine reached a state in which it could fire.

To have the grip to handle this sudden torque, the rider “had to raise the bike.” In 1978, this engine characteristic allowed Kenny Roberts to apply his dirt-track experience to 500CC Grand Prix roadracing. He would get the bike turned early on a tight radius then lift it up to plant it on bigger tire footprints and use the rest of the turn as a curved dragstrip of increasing radius. This style confounded riders raised on the classic “big line” of maximum radius. Using all of their tire grip for turning, they could not apply throttle and thus could not accelerate. Roberts, while slower at his apex, was able by raising the bike to begin accelerating earlier so his exit

speed was greater than that of the big liners. This is the style people would soon call “point and shoot.”

Because four-stroke engines have their strokes separated by mechanical valves, they avoid two-stroke exhaust gas dilution. So as soon as the rider moves the throttle, the engine begins to fire, giving a very small amount of power. This is “the close relationship between the throttle and the back tire” of which Rossi spoke. This made the defensive point-and-shoot riding style unnecessary, so GP riders advancing from 125/250CC GP classes no longer had to forget everything they had learned to adapt to big bikes. In 125, there is too little power to make up a large loss of speed in corners, making high corner speed essential to good lap times. This was also true in 250, which is why in the 500 era we saw some 250 riders fail to fully make the transition to 500. Riders cannot just change their styles because it is a good idea; style is the complex set of reflex loops that are the only safety the rider has. Changing them would be like learning to walk all over again.

Tires began to be built not for the spinning and sliding of point and shoot but for an emerging combination of 125/250 corner speed and smooth fourstroke acceleration. Michelins were not noted for edge grip in the last years of the 500s, for it was observed that “the tire with the best edge grip is not the tire that will push the bike ahead.”

When Bridgestone began development of tires for MotoGP, riders likened them to soft qualifiers—“good in the first corner, but by the next corner it’s down to zero.” Rider Makoto Tamada showed their fast-improving qualities in 2004, but in that season, people referred to cool mornings as “Bridgestone weather” because their still-very-soft tires were at their best before the heat of the day.

Michelin, meanwhile, found it had

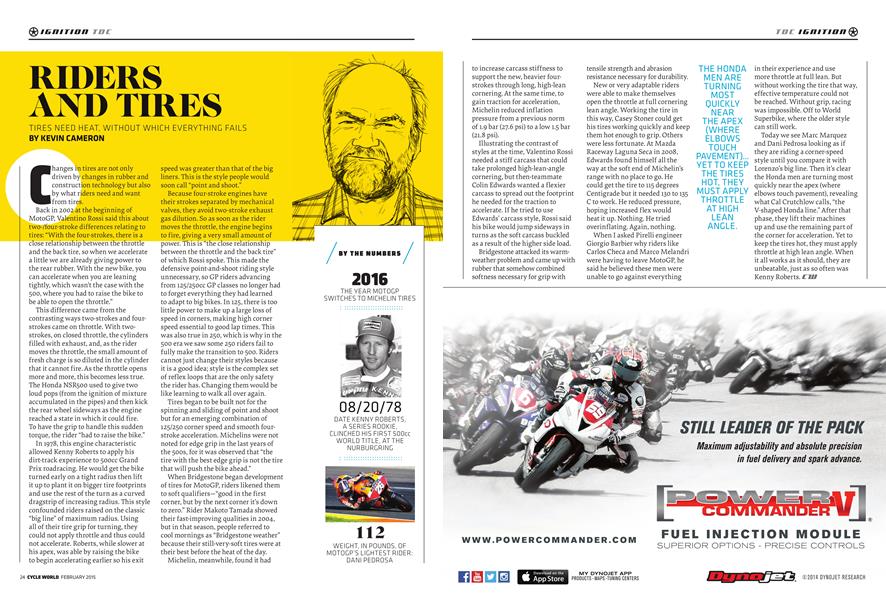

BY THE NUMBERS

2016

THE YEAR MOTOGP SWITCHES TO MICHELIN TIRES

08/20/78

□ATE KENNY ROBERTS,

A SERIES ROOKIE, CLINCHED HIS FIRST 500cc WORLD TITLE, ATTHE NURBURGRING

112

WEIGHT, IN POUNDS, OF MOTOGP’S LIGHTEST RIDER: DANI PEDROSA

to increase carcass stiffness to support the new, heavier fourstrokes through long, high-lean cornering. At the same time, to gain traction for acceleration, Michelin reduced inflation pressure from a previous norm of 1.9 bar (27.6 psi) to a low 1.5 bar (21.8 psi).

Illustrating the contrast of styles at the time, Valentino Rossi needed a stiff carcass that could take prolonged high-lean-angle cornering, but then-teammate Colin Edwards wanted a flexier carcass to spread out the footprint he needed for the traction to accelerate. If he tried to use Edwards’ carcass style, Rossi said his bike would jump sideways in turns as the soft carcass buckled as a result of the higher side load.

Bridgestone attacked its warmweather problem and came up with rubber that somehow combined softness necessary for grip with

tensile strength and abrasion resistance necessary for durability.

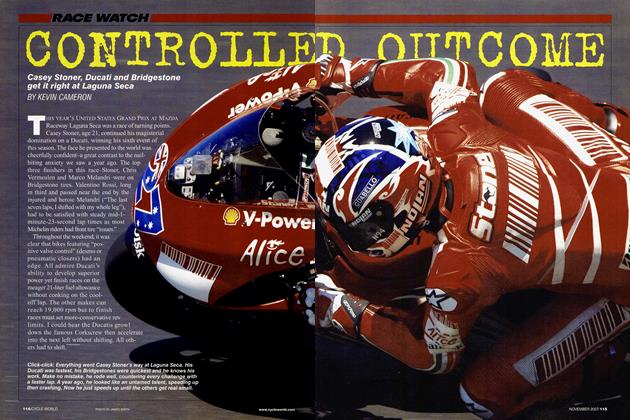

New or very adaptable riders were able to make themselves open the throttle at full cornering lean angle. Working the tire in this way, Casey Stoner could get his tires working quickly and keep them hot enough to grip. Others were less fortunate. At Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca in 2008, Edwards found himself all the way at the soft end of Michelin’s range with no place to go. He could get the tire to 115 degrees Centigrade but it needed 130 to 135 C to work. He reduced pressure, hoping increased flex would heat it up. Nothing. He tried overinflating. Again, nothing.

When I asked Pirelli engineer Giorgio Barbier why riders like Carlos Checa and Marco Melandri were having to leave MotoGP, he said he believed these men were unable to go against everything

THE HONDA MEN ARE TURNING MOST QUICKLY NEAR THE APEX (WHERE ELBOWS TOUCH PAVEMENT)... YET TO KEEP THETIRES HOT, THEY MUST APPLY THROTTLE AT HIGH LEAN ANGLE.

in their experience and use more throttle at full lean. But without working the tire that way, effective temperature could not be reached. Without grip, racing was impossible. Off to World Superbike, where the older style can still work.

Today we see Marc Marquez and Dani Pedrosa looking as if they are riding a corner-speed style until you compare it with Lorenzo’s big line. Then it’s clear the Honda men are turning most quickly near the apex (where elbows touch pavement), revealing what Cal Crutchlow calls, “the V-shaped Honda line.” After that phase, they lift their machines up and use the remaining part of the corner for acceleration. Yet to keep the tires hot, they must apply throttle at high lean angle. When it all works as it should, they are unbeatable, just as so often was Kenny Roberts. E1U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue