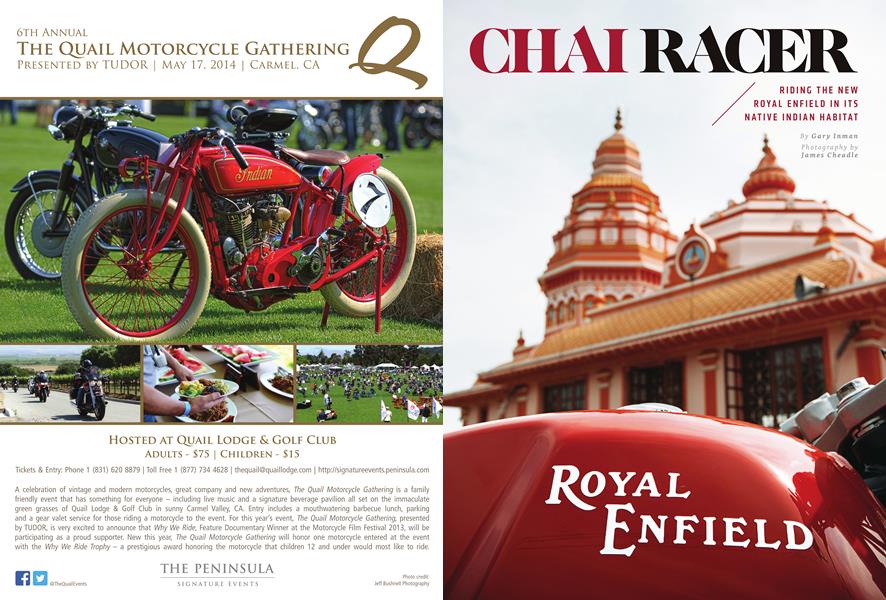

CHAI RACER

RIDING THE NEW ROYAL ENFIELD IN ITS NATIVE INDIAN HABITAT

Gary Inman

The morning's taxi journey is my very first taste of India,

and even here, in the relatively laid-back western beachy tourist area of Goa, it spun my head like a roulette wheel. I can't get into the driver's brain. Why did he set up passes on the entry to every blind corner? Did he really have to sound the horn 300 times during a 30-minute journey? And why did all the motorbikes choose to pull out in front of oncoming traffic?

Now I'm on the same roads, in worse traffic, and the whole scene feels exciting but not intimidating. Everything—the road, traffic, intersections, rules, scenery—is unfamiliar except the controls of the bike I'm piloting, and yet I feel good. It's taken me less than 10 minutes to get in the flow. It is the Royal Enfield Continental GT that is a four-stroke dose of Valium. I'm rarely uncomfortable on a bike, especially on tarmac, even a stretch peppered with an acid-trip circus parade of unlikely and improbable traffic, and I couldn't feel any better. The young lady riding pillion on her husband's 125 while cradling a calf the size of a German shepherd seems as calm as your yoga instructor. Even at 40 mph the calf couldn't look happier, either. What the hell do I have to worry about? Life is sweet.

The idea of coming out to India was to try a Royal Enfield in its native habitat, but the trip took so long to organize, India's most famous manufacturer went and reinvented itself. And now Enfield's latest unitconstruction bike doesn't seem to fit into the landscape, at least in my preconceptions, the same way the borderline-prehistoric pre-unit Bullet did. Not only that, the Indians built a state-of-the-art factory without the faintest whiff of British Empire.

This ride is like each one I've had in a new continent, a complete visual overload. Every minute there's a new question to store and ask someone later. Every time I park and walk back to the Continental GT, it is gleaming like a jewel dropped in a plowed field. The appearance is so alien it takes time to scrutinize the bike and spot things like the less-than-Japanese quality of some of the frame's welds. Enfield has been clever in making the rider's-eye views and all interactions look and feel as good as they possibly could for the money.

I'm in a rural area, nothing built up for miles, no factories to commute to, and within a spit of the Arabian Sea, but I'm riding in an almost constant stream of traffic. Where the hell is everyone going? The kids are in schools, all pristine in matching uniforms that look completely out of place next to the threadbare infrastructure and the piles of dumped rubbish at the side of the road, piles that are grazed by cows. But that, too, is relative. Goa, the smallest state of India, has the highest-rated infrastructure, best standard of living, and is by far the richest region of India—Goans are supposedly 2.5 times richer than the average Indian.

Perhaps that's why there are countless two-wheelers on Goa's roads. Cars, too. And trucks and buses and two-stroke rickshaws. It's not just vehicles on the roads. Tarmac is the preferred bed for the countless stray dogs and cows. Housewives also spread yards of bright red chilies at the side of the road to dry in the sun.

When I see a Royal Enfield waiting to leave a side road, I pull in to talk to the owner. Why buy an Enfield? Without missing a beat the 30-year-old replies, "Because they are the pride of India."

It's an opinion shared by many. Royal Enfield is India's only heritage brand. While not exactly luxury, the bikes were a league above other

Indian-built machines until KTM moved in. They are expensive enough to have an exclusive feel while being significantly more affordable than imported bikes. People aspire to own an Enfield, with current riders often being brought up riding to school on the tank of their father's Bullet.

The Continental GT is the quickest thing on Goa's roads, certainly leaving stoplights. Despite lots of café-racer posturing in its marketing material, the bike can't crack the ton, but that is largely irrelevant in the country that will account for the lion's share of the sales.

Virtually every time I stop, a polite crowd is drawn to the red and chrome and the questions start. "What size is the engine?" is the most popular, followed by queries about fuel consumption. Indians are obsessed with how far a machine can travel on their $5-a-gallon unleaded. Equally popular is, "How much does it cost?" No one seems surprised when I tell them 200,000 rupees—the equivalent of about $3,300 (MSRP in the US is $5,995). Seaside town hustlers ask if they can buy the testbike from me. In two solid days of riding, I'm never asked what the top speed is, the default question where I grew up, in England.

Why buy an Enfield? Without missing a beat the 30-year-old replies, "Because they are the pride of India."

India, I discover, has a habit of bowling a googly (it's like a curveball but in cricket), like when you're hauling down a four-lane highway and it suddenly turns to dirt, wiggles through a shanty town, over a crack in the pavement you could lose a child down, then turns back into a four-lane, making me think, "Did that just happen?"

And Indians appear to be fearless. I don't mean they're especially brave; they just don't have the same fears that have been programmed into many Western minds, mine included. I see a family of three on a IOOCC bike. The toddler, in a knitted bonnet, is in front of dad and fast asleep on the top of the petrol tank at 40 mph.

At the roadside are Hindu temples and, except for the Continental GT, they're the brightest things in the landscape. They're painted in images of fantastical deities. The sight of pastel-colored swastikas on the temples is still remarkable, coming from a culture where the symbol sums up the complete opposite of what it does here.

Not long after thinking perhaps Indian traffic just works—it looks deranged and deregulated, but nothing goes wrong—I see a 50-strong crowd at an intersection. A compact car's windscreen is shattered. In front of it, in a puddle of its own essential fluids, is a bike on its side. I don't stop. I don't see the rider, either. I hope he or she was one of the minority who chose to wear a helmet, even if it is 15 years old with a visor as transparent as a bathroom window.

I don't feel scared or in danger the whole trip, but the unfamiliarity mixed with the comfort of being on a bike built to handle these conditions is making my heart sing. It is what flying hours to ride in these places does to me. Riding a Royal Enfield in India is on the bucket list of riders around the world. It should be, for good reason. CTU

The bike can't crack the ton, but that's largely irrelevant in this country.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Forgotten Tool Kit

April 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

April 2014 -

Still A Winning Formula?

April 2014 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago

April 2014 By Don Canet -

Ignition

IgnitionBecause You Can't Ride Everywhere Travel Like A Pro

April 2014 By Chris Jonnum -

Ignition

IgnitionIntersecting Lives

April 2014 By Freddie Spencer