Power Stations on Wheels

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

THIS IS A CLASSIC TALE THAT WILL BE re-enacted until the asteroid comes: For a variety of often very good reasons, motorcycles grow heavier and heavier until they become nonsense. In our own time, we saw the growth of sportbikes push weight to 600 pounds, triggering a “correction” from Suzuki in the form of its 1985 GSX-R750. Honda’s original CBR900RR and Yamaha’s first “250-sized” YZF-R1 are more recent examples of the industry realizing that weight had outrun performance.

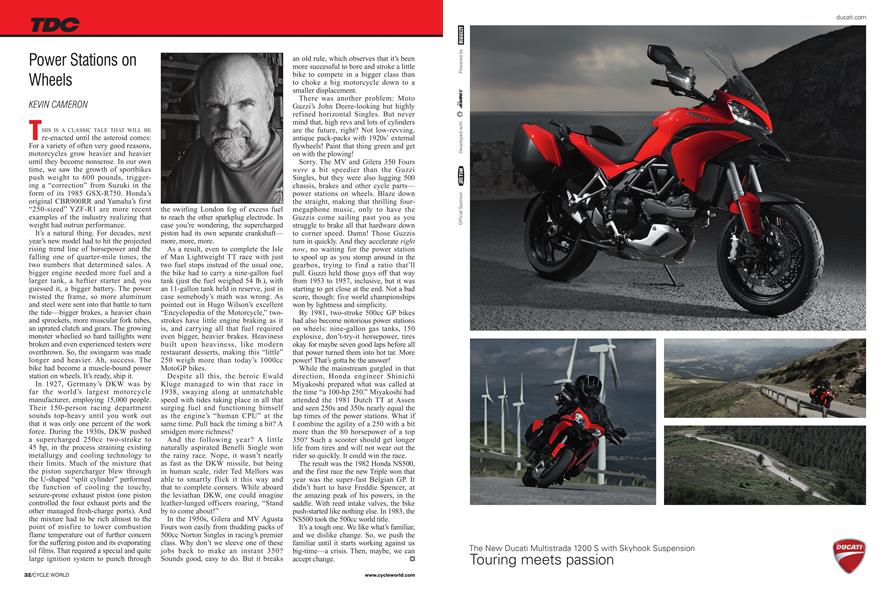

It’s a natural thing. For decades, next year’s new model had to hit the projected rising trend line of horsepower and the falling one of quarter-mile times, the two numbers that determined sales. A bigger engine needed more fuel and a larger tank, a heftier starter and, you guessed it, a bigger battery. The power twisted the frame, so more aluminum and steel were sent into that battle to turn the tide—bigger brakes, a heavier chain and sprockets, more muscular fork tubes, an uprated clutch and gears. The growing monster wheelied so hard taillights were broken and even experienced testers were overthrown. So, the swingarm was made longer and heavier. Ah, success. The bike had become a muscle-bound power station on wheels. It’s ready, ship it.

In 1927, Germany’s DKW was by far the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer, employing 15,000 people. Their 150-person racing department sounds top-heavy until you work out that it was only one percent of the work force. During the 1930s, DKW pushed a supercharged 250cc two-stroke to 45 hp, in the process straining existing metallurgy and cooling technology to their limits. Much of the mixture that the piston supercharger blew through the U-shaped “split cylinder” performed the function of cooling the touchy, seizure-prone exhaust piston (one piston controlled the four exhaust ports and the other managed fresh-charge ports). And the mixture had to be rich almost to the point of misfire to lower combustion flame temperature out of further concern for the suffering piston and its evaporating oil films. That required a special and quite large ignition system to punch through the swirling London fog of excess fuel to reach the other sparkplug electrode. In case you’re wondering, the supercharged piston had its own separate crankshaft— more, more, more.

As a result, even to complete the Isle of Man Lightweight TT race with just two fuel stops instead of the usual one, the bike had to carry a nine-gallon fuel tank (just the fuel weighed 54 lb.), with an 11-gallon tank held in reserve, just in case somebody’s math was wrong. As pointed out in Hugo Wilson’s excellent “Encyclopedia of the Motorcycle,” twostrokes have little engine braking as it is, and carrying all that fuel required even bigger, heavier brakes. Heaviness built upon heaviness, like modern restaurant desserts, making this “little” 250 weigh more than today’s lOOOcc MotoGP bikes.

Despite all this, the heroic Ewald Kluge managed to win that race in 1938, swaying along at unmatchable speed with tides taking place in all that surging fuel and functioning himself as the engine’s “human CPU” at the same time. Pull back the timing a bit? A smidgen more richness?

And the following year? A little naturally aspirated Benelli Single won the rainy race. Nope, it wasn’t nearly as fast as the DKW missile, but being in human scale, rider Ted Mellors was able to smartly flick it this way and that to complete corners. While aboard the leviathan DKW, one could imagine leather-lunged officers roaring, “Stand by to come about!”

In the 1950s, Güera and MV Agusta Fours won easily from thudding packs of 500cc Norton Singles in racing’s premier class. Why don’t we sleeve one of these jobs back to make an instant 350? Sounds good, easy to do. But it breaks an old rule, which observes that it’s been more successful to bore and stroke a little bike to compete in a bigger class than to choke a big motorcycle down to a smaller displacement.

There was another problem: Moto Guzzi’s John Deere-looking but highly refined horizontal Singles. But never mind that, high revs and lots of cylinders are the future, right? Not low-revving, antique pack-packs with 1920s’ external flywheels! Paint that thing green and get on with the plowing!

Sorry. The MV and Güera 350 Fours were a bit speedier than the Guzzi Singles, but they were also lugging 500 chassis, brakes and other cycle parts— power stations on wheels. Blaze down the straight, making that thrilling fourmegaphone music, only to have the Guzzis come sailing past you as you struggle to brake all that hardware down to corner speed. Damn! Those Guzzis turn in quickly. And they accelerate right now, no waiting for the power station to spool up as you stomp around in the gearbox, trying to find a ratio that’ll pull. Guzzi held those guys off that way from 1953 to 1957, inclusive, but it was starting to get close at the end. Not a bad score, though: five world championships won by lightness and simplicity.

By 1981, two-stroke 500cc GP bikes had also become notorious power stations on wheels: nine-gallon gas tanks, 150 explosive, don’t-try-it horsepower, tires okay for maybe seven good laps before all that power turned them into hot tar. More power! That’s gotta be the answer!

While the mainstream gurgled in that direction, Honda engineer Shinichi Miyakoshi prepared what was called at the time “a 100-hp 250.” Miyakoshi had attended the 1981 Dutch TT at Assen and seen 250s and 350s nearly equal the lap times of the power stations. What if I combine the agility of a 250 with a bit more than the 80 horsepower of a top 350? Such a scooter should get longer life from tires and will not wear out the rider so quickly. It could win the race.

The result was the 1982 Honda NS500, and the first race the new Triple won that year was the super-fast Belgian GP. It didn’t hurt to have Freddie Spencer, at the amazing peak of his powers, in the saddle. With reed intake valves, the bike push-started like nothing else. In 1983, the NS500 took the 500cc world title.

It’s a tough one. We like what’s familiar, and we dislike change. So, we push the familiar until it starts working against us big-time—a crisis. Then, maybe, we can accept change.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBeing Prepared

APRIL 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

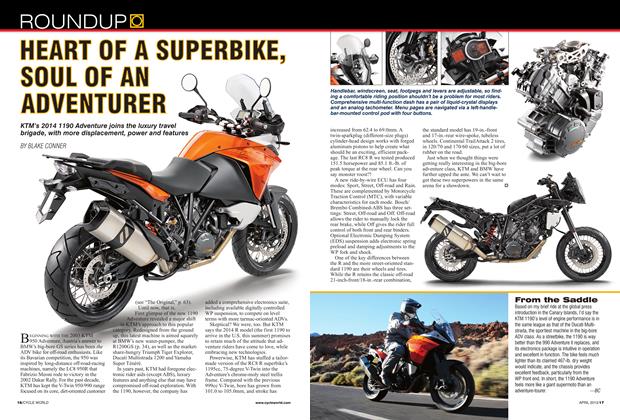

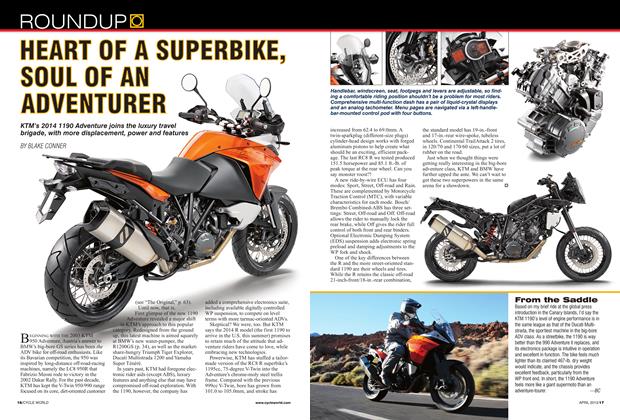

RoundupHeart of A Superbike, Soul of An Adventurer

APRIL 2013 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupFrom the Saddle

APRIL 2013 By BC -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago April 1988

APRIL 2013 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupWill Elastomers Change Helmet Design?

APRIL 2013 By Andrew Bornhop -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

APRIL 2013