Texas Tornado BOOT CAMP

Four days of competition, comedy, male bonding, BBQ eating, beer swilling, gun blasting, child rearing— and learning to ride a TT-R125 like a world champion

JOHN BURNS

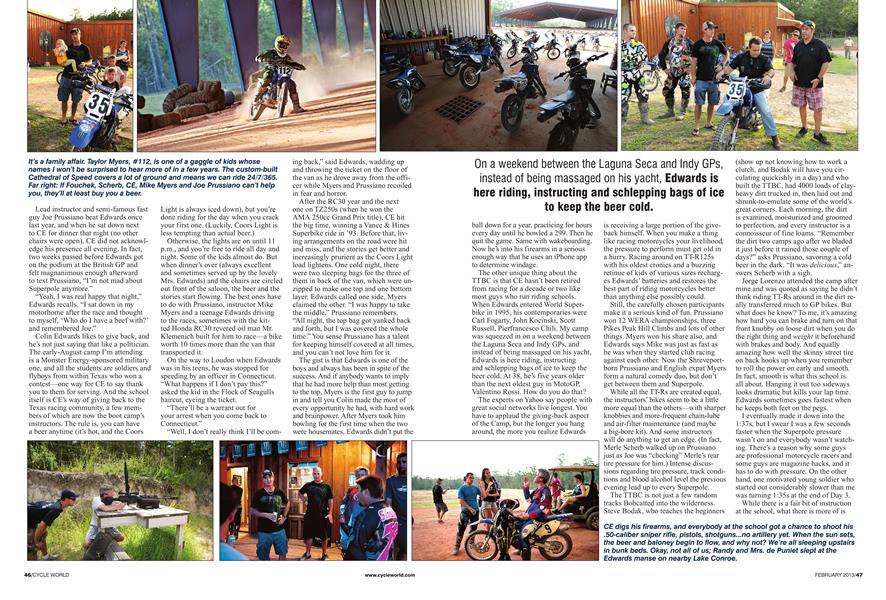

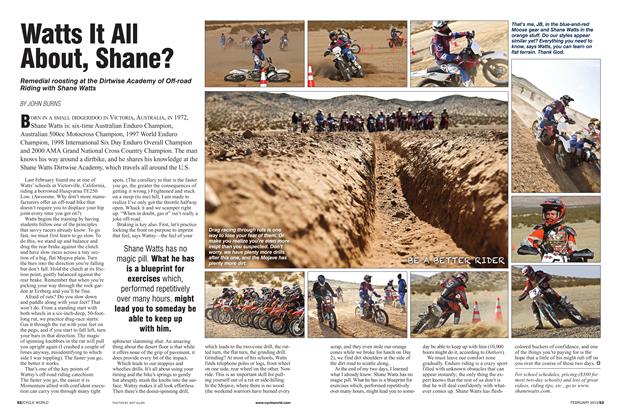

MAYBE THE MOST FUN I EVER HAD ON MOTORCYCLES WAS WHEN my kid was about six and had a KTM 50 and I had a Yamaha TT-R125: He was mass-centralized, had never known fear and had the power-to-weight ratio of a June bug. I was wider, more treacherous and prone to crashing in his path when pressured—a big problem for him and his 12-inch wheels. It all evened out to some dingdong battles in the dirt. Twelve years later, here is Colin Edwards' six-year-old, Hayes, on a KTM 50, and here am I on a TT-R125— turning almost identical lap times. I still got it...

The main difference between Cohn Edwards' Texas Tornado Boot Camp and every other riding school I've attended is mainly this: We are keeping score. At the end of every day, we link the three perfectly groomed main TTBC practice tracks together and run the Superpole. That's 16 turns, I think, and the first day, I did a 1:38 after a couple hours of prac tice. The next day, I did 1:40-something after riding all day. I'Vhat the?! Same as the kid on the KTM.

At every other school I've been to (all of them on pavement except Danny Walker's American Supercamp), the mantra has always been: Ride at a com fortable pace. Do not ride over your head. Nobody's keeping lap times. That's all excellent advice, given that Yamaha R6s and things can be expensive to fix when they jump out from under you. But it leaves a crucial question unanswered: How do you know if you got any faster?

Meanwhile, the people who take Superpole most seriously at the Texas Tornado camp are the instructors, and the most serious instructor is the Texas Tornado himself, who's circulating in the

1 :27s on my second evening at camp. It's Africa-hot and humid in

Montgomery, Texas, during the day but cools off lovely in the evenings when the lights are switched on under the football-field-sized roof About a third of the lap takes place under there before you blast down the hill and circulate the other two tracks, then back again.

I'm not sure if CE is serious or not, but he seems like a man who doesn't kid much when it comes to lap times. He says Superpole at the camp makes him more uptight than qualifying for a MotoGP. Then again, he wasn't exactly happy with his Suter BMW this past year, and nobody expected him to do much on it. That night, instructor/flattracker Merle Scherb runs 1:27.5. Cohn E. runs 1:27.16. And instructor/roadracer Shea Fouchek runs 1:27.32. This is a nearly perfect outcome for instruc tors who'd like to keep being instruc tors. In spite of CE's win, after the high fives and happy talk, his hawk-sharp green eyes lock into a thousand-yard stare; mostly to himself, he says, "I made six or seven mistakes..."

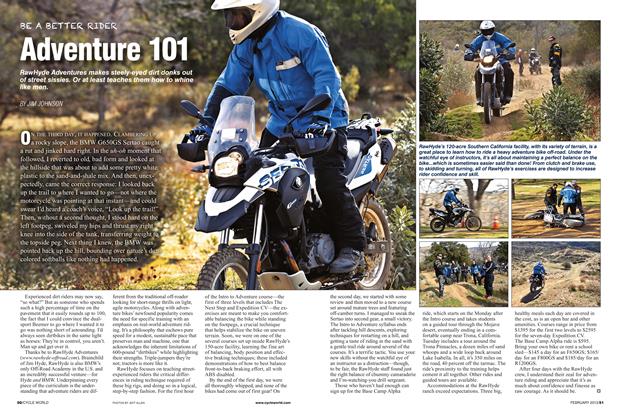

BE A BETTER RIDER

Lead instructor and semi-famous fast guy Joe Prussiano beat Edwards once last year, and when he sat down next to CE for dinner that night (no other chairs were open), CE did not acknowl edge his presence all evening. In fact, two weeks passed before Edwards got on the podium at the British GP and felt magnanimous enough afterward to text Prussiano, "I'm not mad about Superpole anymore."

"Yeah, I was real happy that night," Edwards recalls. "I sat down in my motorhome after the race and thought to myself, `Who do I have a beef with?' and remembered Joe."

Cohn Edwards likes to give back, and he's not just saying that like a politician. The early-August camp I'm attending is a Monster Energy-sponsored military one, and all the students are soldiers and flyboys from within Texas who won a contest-one way for CE to say thank you to them for serving. And the school itself is CE's way of giving back to the Texas racing community, a few mem bers of which are now the boot camp's instructors. The rule is, you can have a beer anytime (it's hot, and the Coors

Light is always iced down), but you're done riding for the day when you crack your first one. (Luckily, Coors Light is less tempting than actual beer.)

Otherwise, the lights are on until 11 p.m., and you're free to ride all day and night. Some of the kids almost do. But when dinner's over (always excellent and sometimes served up by the lovely Mrs. Edwards) and the chairs are circled out front of the saloon, the beer and the stories start flowing. The best ones have to do with Prussiano, instructor Mike Myers and a teenage Edwards driving to the races, sometimes with the kitted Honda RC3O revered oil man Mr. Klemenich built for him to race-a bike worth 10 times more than the van that transported it.

On the way to Loudon when Edwards was in his teens, he was stopped for speeding by an officer in Connecticut. "What happens if I don't pay this?" asked the kid in the Flock of Seagulls haircut, eyeing the ticket.

"There'll be a warrant out for your arrest when you come back to Connecticut."

"Well, I don't really think I'll be com

ing back," said Edwards, wadding up and throwing the ticket on the floor of the van as he drove away from the offi cer while Myers and Prussiano recoiled in fear and horror.

After the RC3O year and the next one on TZ25Os (when he won the AMA 25 0cc Grand Prix title), CE hit the big time, winning a Vance & Hines Superbike ride in `93. Before that, liv ing arrangements on the road were hit and miss, and the stories get better and increasingly prurient as the Coors Light load lightens. One cold night, there were two sleeping bags for the three of them in back of the van, which were un zipped to make one top and one bottom layer. Edwards called one side, Myers claimed the other. "I was happy to take the middle," Prussiano remembers. "All night, the top bag got yanked back and forth, but I was covered the whole time." You sense Prussiano has a talent for keeping himself covered at all times, and you can't not love him for it.

The gist is that Edwards is one of the boys and always has been in spite of the success. And if anybody wants to imply that he had more help than most getting to the top, Myers is the first guy to jump in and tell you Cohn made the most of every opportunity he had, with hard work and brainpower. After Myers took him bowling for the first time when the two were housemates, Edwards didn't put the

On a weekend between the Laguna Seca and Indy GPs, instead of being massaged on his yacht, Edwards is here riding, instructing and schiepping bags of ice to keep the beer cold.

ball down for a year, practicing for hours every day until he bowled a 299. Then he quit the game. Same with wakeboarding. Now he's into his firearms in a serious enough way that he uses an iPhone app to determine windage.

The other unique thing about the TTBC is that CE hasn't been retired from racing for a decade or two like most guys who run riding schools. When Edwards entered World Superbike in 1995, his contemporaries were Carl Fogarty, John Kocinski, Scott Russell, Pierfrancesco Chili. My camp was squeezed in on a weekend between the Laguna Seca and Indy GPs, and instead of being massaged on his yacht, Edwards is here riding, instructing and schlepping bags of ice to keep the beer cold. At 38, he's five years older than the next oldest guy in MotoGP, Valentino Rossi. How do you do that?

The experts on Yahoo say people with great social networks live longest. You have to applaud the giving-back aspect of the Camp, but the longer you hang around, the more you realize Edwards

is receiving a large portion of the giveback himself When you make a thing like racing motorcycles your livelihood, the pressure to perform must get old in a hurry. Racing around on TT-R125s with his oldest cronies and a buzzing retinue of kids of various sizes recharg es Edwards' batteries and restores the best part of riding motorcycles better than anything else possibly could.

Still, the carefully chosen participants make it a serious kind of fun. Prussiano won 12 WERA championships, three Pikes Peak Hill Climbs and lots of other things. Myers won his share also, and Edwards says Mike was just as fast as he was when they started club racing against each other. Now the Shreveportborn Prussiano and English expat Myers form a natural comedy duo, but don't get between them and Superpole.

While all the TT-Rs are created equal, the instructors' bikes seem to be a little more equal than the others-with sharper knobbies and more-frequent chain-lube and air-filter maintenance (and maybe a big-bore kit). And some instructors will do anything to get an edge. (In fact, Merle Scherb walked up on Prussiano just as Joe was "checking" Merle's rear tire pressure for him.) Intense discus sions regarding tire pressure, track condi tions and blood alcohol level the previous evening lead up to every Superpole.

The TTBC is not just a few random tracks Bobcatted into the wilderness. Steve Bodak, who teaches the beginners

(show up not knowing how to work a clutch, and Bodak will have you cir culating quickishly in a day) and who built the TTBC, had 4000 loads of clayheavy dirt trucked in, then laid out and shrunk-to-emulate some of the world's great corners. Each morning, the dirt is examined, moisturized and groomed to perfection, and every instructor is a connoisseur of fine loams. "Remember the dirt two camps ago after we bladed it just before it rained those couple of days?" asks Prussiano, savoring a cold beer in the dark. "It was delicious," an swers Scherb with a sigh.

Jorge Lorenzo attended the camp after mine and was quoted as saying he didn't think riding TT-Rs around in the dirt re ally transferred much to GP bikes. But what does he know? To me, it's amazing how hard you can brake and turn on that front knobby on loose dirt when you do the right thing and weight it beforehand with brakes and body. And equally amazing how well the skinny street tire on back hooks up when you remember to roll the power on early and smooth. In fact, smooth is what this school is all about. Hanging it out too sideways looks dramatic but kills your lap time. Edwards sometimes goes fastest when he keeps both feet on the pegs.

I eventually made it down into the 1:37s, but I swear I was a few seconds faster when the Superpole pressure wasn't on and everybody wasn't watch ing. There's a reason why some guys are professional motorcycle racers and some guys are magazine hacks, and it has to do with pressure. On the other hand, one motivated young soldier who started out considerably slower than me was turning 1:35s at the end of Day 3.

While there is a fair bit of instruction at the school, what there is more of is

being sucked along in the vacuum of instructors, grommets and faster guys in training for the next Superpole. After enough humanity slides sideways past you on the outside entering the hairpin, you can't help but wise up and join them.

By Day 4,1 am having to drop my pants on the floor to put them on, since I can't lift my feet anymore. But once on the bike, I'm good to go, and by now, I've got it down. With the brakes on and the fork compressed to make the knobs grip and the bike turn, you can brake a lot later and all the way to the apex. And if you already have the gas cracked open and the rear rotated a little before you get there and ease all the way off the front brake (thanks, Cohn), you can make that transi tion to driving off the corner smooooth and fast. Once you're on the gas, stay on it to keep the weight transferring and the chassis steady! So natural. So easy. But most people need three or four days to get there, which is why the TTBC doesn't like to do two-day camps.

Speaking of getting it, the people re ally getting it here are the kids. Myers' son, Taylor, is 13 years old and already down in the 1 :27s. You'd swear that's Jay Springsteen sliding around the dirt oval until he pulls in for a drink and only comes up to your nipples. Jimmy Newton smoked up the best brisket most of us ever had one night (including a rave review from the three-star general's per sonal chef who was at the school), and his kid, Jay Newton, is right on Taylor's tailsection. Thane Bodak is 10 and also crazy fast. Hanging out with the kids and parents is a trip back to Mayberry. Go take a shower now, son, or no riding tomorrow. Aw, shucks, do I have to? (If you're one of those fanatical racing par ents, probably the best thing you can do is quit your job now and apply for a posi tion at the TTBC. Any position.)

Saturday night, the Tornado takes the night off from Superpole, as is his wont, and runs the stopwatch. "Fooch" Fouchek runs another 1:27.32 just like

last night, and Scherb-in training for the Indy Mile-throws down a ballerinagraceful 26.30. Prussiano's 28.92 is injurious enough to his self-esteem, but Myers adds insult by running 28.78. Prussiano is wounded to the core, but only for about a minute. The show must go on. Scherb and Fouchek laugh and backslap that for sure it could easily go the other way next time, with the old guys back on top (not that they call Joe and Mike old guys to their faces), and the old guys buy it one more time.

And then it's beer time, and all the bench racing starts again. Remember when Josh Hayes and all those AMA guys were here? The tension was so thick you couldn't bend it with a tire iron. Your correspondent is a pathetic journalist too slow for contempt, but woe be to the fast young smart-ass who shows up at the TTBC and gets beat by Prussiano and Myers, as quite a few do. Joe will want to know, with his drawling smile, how does it feel to get beat by an old, fat TV sales man (Mike runs a high-end audio-video business) and a fat old semi-retired gigo lo? Myers might ask, in what's left of his genteel English accent, if you'd like to be tucked in now so you'll have plenty of rest to try again tomorrow? Gracious in defeat, humble in victory. And chuckling through all of it in the soft Texas night with a cold beer and the luxuriously deep satisfaction that one of their own hit it re ally, really big-close enough to taste the champagne on their own tongues-and brought it home again.

For me, it was all painless in spite of a few get-offs and scrapes, and more fun than I've had in many moons. At $2250, the four-day camp isn't cheap, but that includes lodging, three squares a day, as much Coors Light as your liver can pro cess (mine waves Coors Light straight through), a motorcycle to ride, gear to wear, guns to shoot and non-stop live entertainment. You'll also be smoother and more in control of your motorcycle than ever. Highly recommended.

Colin E's 10 (or so) Commandments

Here are some of the main technical points offered by the Texas Tornado Boot Camp, which you get to apply with great repetition at the school with tons of seat time.

o Eyes up! Look where you want to go.

o Sm00000th inputs are key: slow on the gas, gentle-onset braking.

o Blend brakes and throttle to minimize the time from off-brakes to on-throttle... which leads to finding neutral throttle. Advanced technique: Crack the gas open before you're all the way off the brakes.

o Throttle control keeps the chassis steady! From off-throttle to pinned is one constant motion. Once you're opening the throttle, neutral is okay but rolling off is a no-no.

o Elbows out for maximum control, and grip the throttle like a screwdriver, not a caveman club.

O Scoot to the front in the turns, sit on top of the bike and understand why Valentino hangs that inside leg off: It's a balance pole.

o Compress the fork with the brakes and your weight to steepen rake and make the bike want to turn. In the dirt, use both brakes in every corner.

o Push the bike down while keeping your spine perpendicular and shoulders parallel to ground; again, we're sitting on top of the leaned-over bike. (Body position in the dirt is the only thing that doesn't transfer to roadracing.)

o Weight that outside footpeg!

q~j Slow down to go fast. (This doesn't work for really slow people, who should attempt to go faster.)

• Relax. You're not really rolling `til your TT-R is rocking. Your bike will tell you when you're on the edge, but you can't feel it if your body is ultra-tense.

Keep close track of your tire pressures but even closer track of your opponents' tire pressures...

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCar Connections

February 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

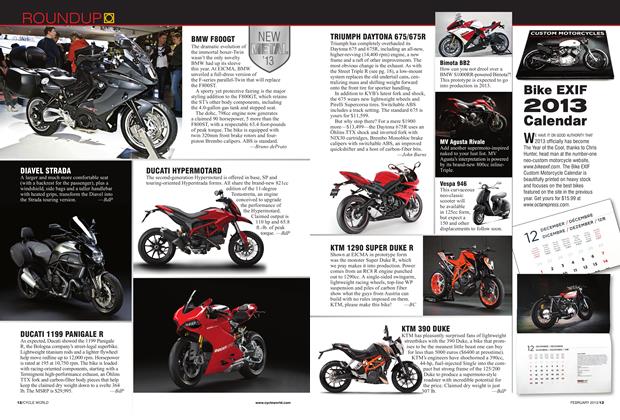

RoundupBike Exif 2013 Calendar

February 2013 -

Roundup

RoundupOn the Record: Nicky Hayden

February 2013 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Rc1000v?!

February 2013 By John Burns -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago February 1988

February 2013 By John Burns -

Roundup

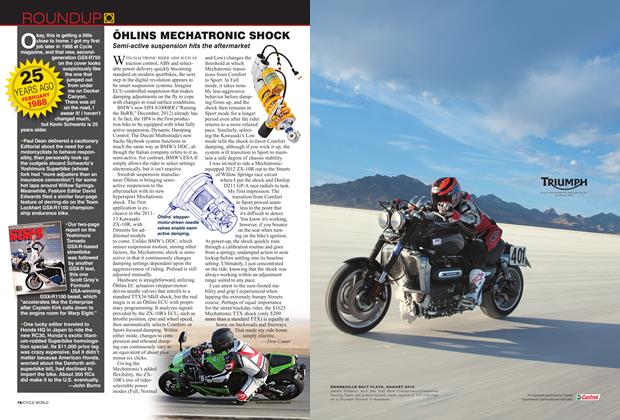

RoundupÖhlins Mechatronic Shock

February 2013 By Don Canet