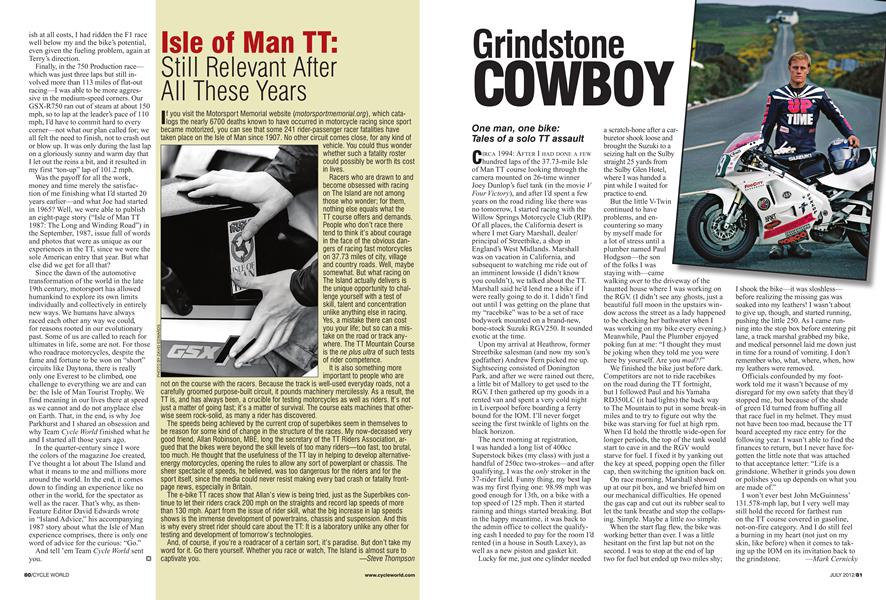

Grindstone COWBOY

One man, one bike: Tales of a solo TT assault

CIRCA 1994: AFTER I HAD DONE A FEW hundred laps of the 37.73-mile Isle of Man TT course looking through the camera mounted on 26-time winner Joey Dunlop’s fuel tank (in the movie V Four Victory), and after I’d spent a few years on the road riding like there was no tomorrow, I started racing with the Willow Springs Motorcycle Club (RIP). Of all places, the California desert is where I met Gary Marshall, dealer/ principal of Streetbike, a shop in England’s West Midlands. Marshall was on vacation in California, and subsequent to watching me ride out of an imminent lowside (I didn’t know you couldn’t), we talked about the TT. Marshall said he’d lend me a bike if I were really going to do it. I didn’t find out until I was getting on the plane that my “racebike” was to be a set of race bodywork mounted on a brand-new, bone-stock Suzuki RGV250. It sounded exotic at the time.

Upon my arrival at Heathrow, former Streetbike salesman (and now my son’s godfather) Andrew Fern picked me up. Sightseeing consisted of Donington Park, and after we were rained out there, a little bit of Mallory to get used to the RGV I then gathered up my goods in a rented van and spent a very cold night in Liverpool before boarding a ferry bound for the IOM. I’ll never forget seeing the first twinkle of lights on the black horizon.

The next morning at registration,

I was handed a long list of 400cc Superstock bikes (my class) with just a handful of 250cc two-strokes—and after qualifying, I was the only stroker in the 37-rider field. Funny thing, my best lap was my first flying one: 98.98 mph was good enough for 13th, on a bike with a top speed of 125 mph. Then it started raining and things started breaking. But in the happy meantime, it was back to the admin office to collect the qualifying cash I needed to pay for the room I’d rented (in a house in South Laxey), as well as a new piston and gasket kit. Lucky for me, just one cylinder needed a scratch-hone after a carburetor shook loose and brought the Suzuki to a seizing halt on the Sulby straight 25 yards from the Sulby Glen Hotel, where I was handed a pint while I waited for practice to end.

But the little V-Twin continued to have problems, and encountering so many by myself made for a lot of stress until a plumber named Paul Hodgson—the son of the folks I was staying with—came walking over to the driveway of the haunted house where I was working on the RGV (I didn’t see any ghosts, just a beautiful full moon in the upstairs window across the street as a lady happened to be checking her bathwater when I was working on my bike every evening.) Meanwhile, Paul the Plumber enjoyed poking fun at me: “I thought they must be joking when they told me you were here by yourself. Are you mad?!”

We finished the bike just before dark. Competitors are not to ride racebikes on the road during the TT fortnight, but I followed Paul and his Yamaha RD350LC (it had lights) the back way to The Mountain to put in some break-in miles and to try to figure out why the bike was starving for fuel at high rpm. When I’d hold the throttle wide-open for longer periods, the top of the tank would start to cave in and the RGV would starve for fuel. I fixed it by yanking out the key at speed, popping open the filler cap, then switching the ignition back on.

On race morning, Marshall showed up at our pit box, and we briefed him on our mechanical difficulties. He opened the gas cap and cut out its rubber seal to let the tank breathe and stop the collapsing. Simple. Maybe a little too simple.

When the start flag flew, the bike was working better than ever. I was a little hesitant on the first lap but not on the second. I was to stop at the end of lap two for fuel but ended up two miles shy; I shook the bike—it was sloshless— before realizing the missing gas was soaked into my leathers! I wasn’t about to give up, though, and started running, pushing the little 250. As I came running into the stop box before entering pit lane, a track marshal grabbed my bike, and medical personnel laid me down just in time for a round of vomiting. I don’t remember who, what, where, when, how my leathers were removed.

Officials confounded by my footwork told me it wasn’t because of my disregard for my own safety that they’d stopped me, but because of the shade of green I’d turned from huffing all that race fuel in my helmet. They must not have been too mad, because the TT board accepted my race entry for the following year. I wasn’t able to find the finances to return, but I never have forgotten the little note that was attached to that acceptance letter: “Life is a grindstone. Whether it grinds you down or polishes you up depends on what you are made of.”

I won’t ever best John McGuinness’ 131.578-mph lap, but I very well may still hold the record for farthest run on the TT course covered in gasoline, not-on-fire category. And I do still feel a burning in my heart (not just on my skin, like before) when it comes to taking up the IOM on its invitation back to the grindstone. —Mark Cernicky

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCharacters In Exile

JULY 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAvon 3d Ultra Radial Tires

JULY 2012 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupNorton To Tackle Tt

JULY 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1987

JULY 2012 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

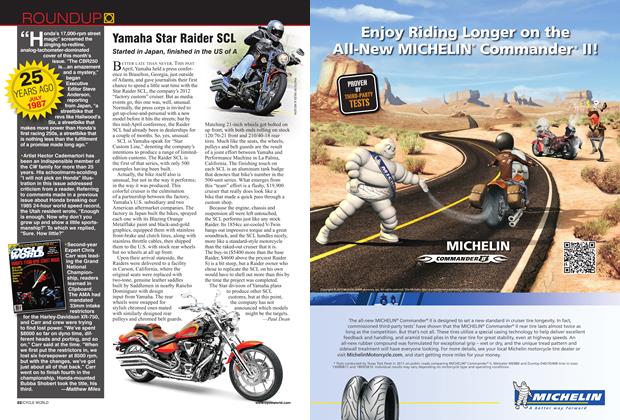

RoundupYamaha Star Raider Scl

JULY 2012 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupOn the Record: Claudio Domenicali

JULY 2012 By Bruno Deprato