Directing Traffic

LEANINGS

PETER EGAN

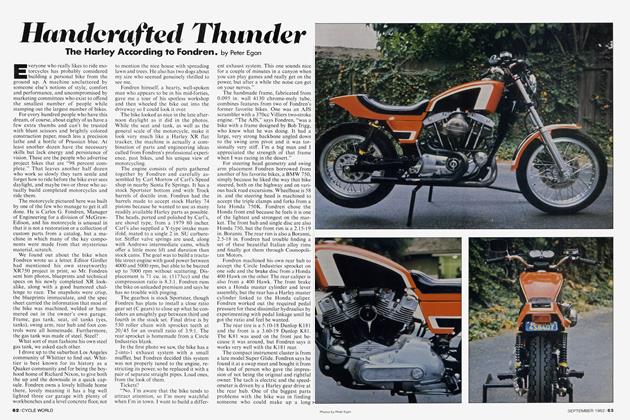

WELL, OUR SLIMEY CRUD CAFÉ Racer Run was a big success this past fall. I’ve never been any good at estimating crowds, but those with adding machines behind their eyeballs assured me we had more than 1000 motorcycles show up for this biennial ride from Pine Bluff to Leland, Wisconsin.

The perfect autumn weather helped, and bikes came pouring in from three or four surrounding states, if you count Illinois—which many of my Illinois friends do, even though they have no true hills or curves. It seems cruel to remind them, but sometimes I can’t help it.

The starting point for this ride is about 30 miles from my home, so I got up early and took scenic backroads on my Buell Ulysses, cutting though swirls of yellow and red autumn leaves and inhaling the pure country air, which is supposed to be good for you. This theory may precede the advent of large “factory farm” feedlots, however. I can now hold my breath longer than a Navy Seal.

I hung out in Pine Bluff for a while, then headed for Leland through the woodsy hills.

Right after turning north onto Highway 78, I came upon an accident scene, with police cars and an ambulance. A cop was emphatically directing traffic, so I didn’t stop to help—or slow down much to gawk. A passing glimpse, however, revealed a group of riders standing around, the bottom of a motorcycle on its side (Triumph Triple?) and—strangely—a neatly folded stack of riding gear on the roadside, with a helmet on top.

When I got to Leland, I mentioned this scene to a group of guys, and an old acquaintance named Ray said, “I’m the one who stacked that gear next to the road. I saw the whole accident.”

Ray said a group of bikes had been stopped on the road with their left turnsignals on when it appeared the aboutto-be injured rider tried to pass them on the left, just as they were turning. Bad idea. He T-boned the front end of one of the bikes and crashed, with some injuries, but apparently nothing critical.

I was glad to hear the rider was still with us, despite his apparent lapse of judgment. I was also glad not to be one of the first on the scene.

1 really hate directing traffic.

That phrase, in fact, has become my personal code for impending disaster. If I’m on a group ride where the red mist sets in and people (especially me) start riding over their heads, I mutter to myself, “Before long, someone will be directing traffic.”

I’ve done this unenviable job myself at least three times.

The first occasion was in late 1989 when Barb and I rode from CWs Newport Beach office up to Laguna Seca for the USGP on our first Honda STI 100 testbike. On the way home, we took some backroads through the mountains and came across a group of Honda dealers trying out new Pacific Coast 800s.

One of them had collided with the left front fender of a car in a blind corner. The car was dented and the rider had broken his leg, while the Pacific Coast had an ugly gash of missing bodywork down that side.

Japanese manufacturers seldom waste a lot of money making hidden parts look elegant, and I remember thinking the bike looked like something from The Terminator, where an android peels back the skin on his wrist and you can see all the hydraulic rods and wire bundles.

Barb and I directed traffic around the crash scene while the rider’s friends looked after him. The man was in considerable discomfort, and it took forever for the ambulance to show up. When it finally got there, I had a tension headache from willing it to arrive. Empathy beats injury hands down, but it still takes something out of you.

The next episode was a lot more fun, just because no one—including the motorcycle—got hurt. 1 hope I can mention this one again without getting fired.

A bunch of us staffers were attending the Honda Hoot in Knoxville, riding on

a winding mountain road near the Blue Ridge Crest. We were whistling along pretty good on our VFR800 Interceptors when MR. HOYER, our now-EDITOR, glanced in his mirror briefly to make sure everyone was still behind him, then entered a tight corner too fast and went straight off a cliff, taking part of a rusty old barbed-wire fence with him.

I sez to myself, “Well, this can’t be good.”

But by the time 1 turned around, Mark’s hand was already reaching over the edge of the precipice as he pulled himself back up onto level ground. It was like a Wiley Coyote cartoon. I resisted the urge to hand him an anvil from the Acme Anvil Company.

Mark wasn’t the least bit hurt, and his bike was down below, lying on top of a big bush, with hardly a scratch on it.

Some of us are just blessed. I’m surprised he didn’t land in an inflatable swimming-pool chair with an umbrella drink in the armrest.

Anyway, I spent the afternoon directing traffic while a tow truck winched the bike back up to the road. Got to meet a nice couple who stopped on their KTM 950 Adventure to see if we were okay. Their bike was just like my old one. After a few hours of staring at their parked bike, I was inspired to go home and buy another new 950.

So what happened to my old KTM?

Well, on a Saturday ride, I’d traded bikes with my friend Greg Rammel, who had a Ducati Multistrada. Greg went pretty hot into a tightening left-hander and, as an experienced roadracer, overestimated the amount of grip available from my spindly semi-knobby adventuretouring tires—i.e., almost none. He skillfully slid both ends, then disappeared into the woods and broke his knee badly on a small tree.

I directed traffic that afternoon and got another migraine from wishing for the ambulance to come, as Greg was not feeling any too chipper. Luckily, this one got there a lot faster; cell phones had arrived.

So far, I’ve avoided having traffic directed on my behalf. All my injury/ bone-breaking crashes have occurred off-road, on trails so remote I had to be my own ambulance and ride out.

I suppose this means I need a separate phrase for impending disaster in the dirt. One that might work is, “I guess we’ll soon be needing the Vicodin.”

For those moments just after a dirt crash, I’ve found it’s also useful to practice the phrase, “No sense taking that boot off ’til we get to a hospital.” E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBreaking Up (is Hard)

March 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupÖhlins Electronic Suspension

March 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupMeet the New Guy

March 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha Y125 Moegi

March 2012 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupDo It For the Children

March 2012 By John Burns, Paul Dean -

Roundup

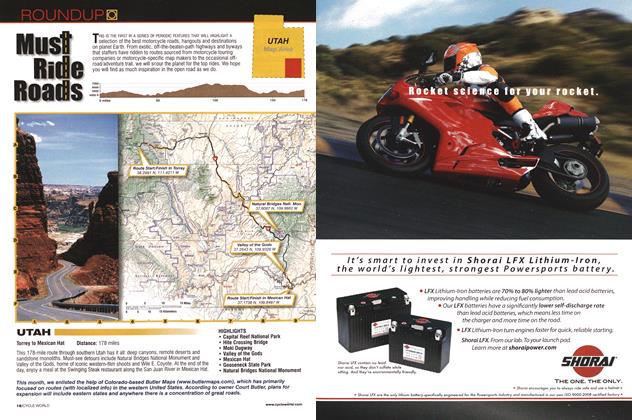

RoundupMust Ride Roads

March 2012