SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Rain of terror

Q My Triumph Bonneville T100 is approaching 12,000 miles and has run trouble-free with one exception. On three occasions while cruising at highway speed, the engine staggered and stopped. The first time it happened, it seemed much like the fuel starvation symptoms one experiences when it’s time to go on Reserve, but I knew the tank had ample fuel. As a hunch,

I opened the gas filler cap and heard a hiss, obviously relieving vacuum in the tank. The bike then restarted and ran fine. The second two occasions were similarly rectified by opening the fuel filler cap. Here’s the mystery: On each occasion, I was riding through a significant downpour. Why is the bike developing vacuum in the fuel tank when riding in the rain, but the problem never occurs in the dry? Tom Sladek Green Bay, Wisconsin

A That is a weird one, but I think there’s a logical explanation for it. As I explained to another reader in

December’s Service, the gas tanks on streetbikes are fitted with a one-way valve, usually in the filler cap, that lets air enter the tank to compensate for the drop in fuel level as fuel is consumed, but it does not permit fuel vapors from exiting the tank into the atmosphere. Somehow, water is working its way into the valve in your Triumph’s cap as you ride in a heavy rainstorm, preventing the valve from opening.

I’ve never seen the inner workings of a T 100’s filler cap and, in fact, don’t even know if they can be taken apart, so I can’t explain how such a phenomenon could happen, but it obviously does. Rather than attempting to repair the cap, it could be easier and more expedient just to replace it. Since it’s a simple screw-on cap rather than the aircraftstyle flip-up type, new ones are much less expensive, priced at around $40.

Speeding pistons

Ql have a question about piston speed. Pistons do not run at constant speeds but are always either speeding up or slowing down, so how is their speed measured? If I read that an engine has a piston speed of 4000 feet per minute, is that the pistons’ peak speed or their average speed or some other measure of their speed? This isn’t information vital to my lifelong love of motorcycles; I’m just an enthusiast who would like to know. Keith Marshall Bakersfield, California

A Excellent question, Keith, and your second guess, average speed, is the correct answer. Indeed, not only does a piston continuously speed up and slow down, it comes to a complete stop twice during every crankshaft revolution—once at Top Dead Center, again at Bottom Dead Center. This subjects a piston to tremendous rates of acceleration and deceleration as it shuttles back-and-forth from TDC to BDC. At higher rpm, a piston in a modern sportbike might have to accelerate from zero to 60 mph in just two or three onethousandths of a second, then decelerate back to zero in essentially the same amount of time. This means that in an engine with a rated piston speed of, to use your example, 4000 feet per minute, the piston might reach peak speeds well in excess of 6000 fpm.

Although engine designers must calculate maximum piston acceleration rates as well as peak piston speeds, the standard statistic is average fpm. This is derived by calculating the distance the piston must travel in one minute at any given rpm, regardless of its maximum or minimum speeds. When working in the SAE measurement system, the simple formula is: piston speed = stroke (in inches) x 2 x rpm 12 (to convert inches to feet). So, if we have, for example, a lOOOcc Kawasaki ZX-10R engine with a 55mm (2.165-in.) stroke spinning at 10,000 rpm, the piston speed at that point would be 3609 fpm, calculated by multiplying 2.165 by 2 (4.3307), multiplying that number by 10,000 (43307), then dividing by 12 to get 3609. The 10R, however, has a 14,000-rpm redline, so, the average piston speed at that point is a whopping 5052 fpm.

No idle threat

I own an exceptionally clean, low-mileage 2005 Suzuki Bandit 1200S that I unfortunately had to leave sitting unridden for a year and a half while I was working on a company project in Poland. Since my return, the engine has been very difficult to start and refuses to idle. It runs normally if I ride it wide-open, but it’s herky-jerky when just cruising on the highway and a pain in the neck to keep the engine running around town. I ran some carburetor cleaner through the system, but it didn’t seem to help. Any advice you could offer would be highly appreciated.

Will Corrigan Stamford, Connecticut

A Since you made no claims to the contrary, I assume that when you parked the Bandit before departing for Poland, you did not drain the gas tank or carburetors, and neither did you put any fuel stabilizer, such as Sta-Bil, in the tank. Also, the diaphragm on your Bandit’s vacuum-controlled petcock may have allowed some additional gas to slowly leak into the carbs over time.

In any event, the volatile components of the gasoline in the float bowls gradually evaporated while you were gone, leaving behind a gummy residue that eventually hardens into a varnish-like substance. Among other problems the varnish might cause, it usually completely plugs up the tiniest orifices in the float bowls, the pilot (idle) jets. This explains why the engine is hard to start and won’t idle—and also why it runs erratically when cruising. At cruising speeds, the throttle is only cracked open a small amount, so the pilot jets normally contribute to the fuel mixture; if those jets are clogged, the mixture will be too lean, causing the engine to buck and surge.

Your attempt to fix the problem with carb cleaner was a valiant effort, but that tactic almost always is futile when the pilot jets are plugged. Carb cleaner has to run through an orifice in order to clean it, which it can’t do if the jet is completely blocked.

There are just two remedies, really: 1) remove and clean the pilot jets either by soaking them in a professional-quality carb-cleaning solvent or reaming them with a single strand of electrical wire; or 2) replace them at a cost of somewhere around $60 (approx. $14 each).

I highly recommend door number two. To meet emissions standards, the Bandit 1200’s pilot jetting already is on the lean side; and the orifices in those jets are so small that even a minute amount of remaining residue or scratches caused by the electrical wire could further lean the mixture. Replacing the jets eliminates that possibility.

Actually, while you have the carbs apart, you might consider installing an aftermarket jet kit. That would not only riehen the pilot mixture closer to the ideal air/fuel ratio but would also sharpen the performance and throttle response everywhere throughout the rpm range. I suggest the Stage 1 kit from Dynojet (www.dynojet.com), which, for your Bandit, is part #3151 with a suggested retail price of $125.89.

Foul play

Having been in motorcycling for many years as an MX racer and all-around enthusiast, I’ve often been mystified by fouled sparkplugs. I understand an oil-fouled plug and its reason for not firing properly, but during my years racing two-stroke dirtbikes and still an occasional vintage MX, I’ve never understood exactly what happens to a perfectly finelooking sparkplug to make it foul. Since high-performance four-strokes are now the dominant off-road bikes, I am again mystified why they also foul plugs, although it doesn’t seem to happen as often as with a two-stroke. I understand the jetting and oil consumption part of the equation but can you please shed some light on what actually happens to a plug when it fouls? Roger Harris Vicksburg, Mississippi

A Simply put, sparkplug fouling occurs when a plug conducts electricity in places where it normally does not. The center electrode of a plug extends from the upper contact to which the plug wire connects, all the way through the middle of the plug’s body and terminates in the short, exposed end that pokes down into the combustion chamber. Directly across a small (usually .025to .035-in.) gap from the center electrode is the ground electrode, which is part of the plug’s main steel body and becomes grounded when the plug is threaded into the engine. In between the center and ground electrodes is a ceramic insulator that does not conduct electricity, thus preventing current from traveling between one electrode to the other until it is forced to jump the gap, which creates a spark in the combustion chamber.

That all changes when a plug becomes fouled. Sometimes, a two-stroke engine, in which a small amount of oil is mixed with each dose of fuel, cannot fully or cleanly burn all the oil in the mixture, resulting in an oily residue that accumulates on the ceramic insulator. This can be caused by a number of conditions, such as a toorich air-fuel mixture, too much oil in the fuel or even a sparkplug that is too cold-running to burn the deposits off of the insulator. Because these oily deposits conduct electricity, the spark current “shorts out,” finding it much easier to travel from the center electrode, up along the outside of the insulator and over to the grounded plug body, all without producing a spark. Without a spark, that cylinder does not fire. The plug is fouled.

A similar occurrence can take place in a four-stroke, usually because the fuel mixture is far too rich, preventing complete burning of the mixture. Incomplete combustion leaves behind a carbon residue on the insulator that, just like oil deposits, conducts electricity, causing the plug to foul. A four-stroke that has an oil-consumption problem (worn piston rings or valve guides) also can foul plugs due to oil deposits on the insulators.

New-old anxiety

Ql am thinking about buying a “new” leftover sportbike, a 2009 Yamaha YZF-R6. The bike is still in its original crate from the factory, so it’s never been ridden. I would like to know if I should have any concerns about parts sticking and drying up, especially engine internals. Are motorcycles usually shipped with or without oil, and are they started at the factory? I hope you can help me out. Shawn Leger Submitted via www.cycleworld.com

A Without knowing the environment in which the bike has been stored since 2009 (inside or outside, damp or dry, heated or unheated, etc.), I can’t be certain about the condition of its engine and related components.

I do know, however, that new motorcycles—including Yamahas—are started and briefly run at the end of their assembly lines, and that they are then shipped without engine oil.

On the other hand, you are, by far, not the only person ever to buy such a motorcycle. The financial crisis that has been hanging around since 2008 dramatically slowed new motorcycle sales, causing inventory of unsold units to pile up in warehouses and dealerships. This has allowed literally thousands of riders to buy “carryover” bikes at bargain-basement prices. And as far as I am aware, there hasn’t been a rash of internal engine problems with those machines. Besides, if you are buying the R6 from a dealer, its original Yamaha factory new-bike warranty should still be in effect; so, if the bike were to need any engine repairs, they would be covered by the warranty.

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mall a written Inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631 -0651; 3) e-mail It to CW1Dean@aol.com; or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CI/I/ Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10page essay, but if you’re looking for help In solving a problem, do Include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of Inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

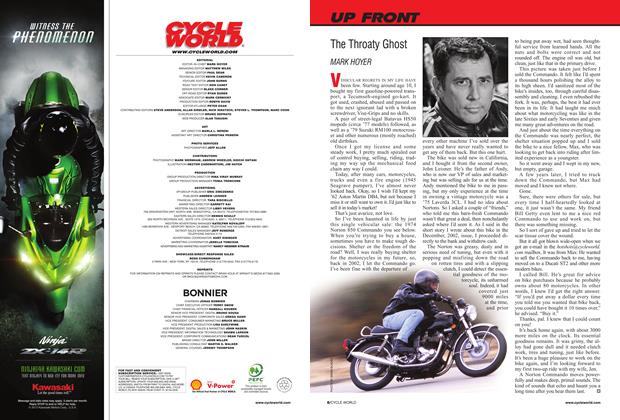

Up FrontThe Throaty Ghost

FEBRUARY 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupWhat's the Two-Wheel World Coming To Anyway?

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

25 Years Ago February 1987

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Zeros

FEBRUARY 2012 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupDaineses D-Air Street

FEBRUARY 2012 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupMilestones Along the Way

FEBRUARY 2012 By Paul Dean