UP FRONT

That Feeling

MARK HOYER

THERE IS THAT MOMENT IN LIFE WHEN the light just switches on. In a flash, there is no doubt that every molecule of your being seeks one thing and one thing only: delicious movement of the kind only delivered by two wheels and an engine.

It can happen the first time you see a motorcycle of distinction when you are very young (like it did for me) or it can happen the first time you take, or even get, a ride on a motorcycle. It can happen in a million ways, and does, because what that light illuminates is a fundamental truth: Seeking speed and exercising balance are part of the human condition. There are many paths toward this natural expression of humanity, but we know motorcycling is the best one. After that, it gets more complex.

My first memorable ride on a motorized two-wheeler came on a Honda XR75. I didn’t care what it was; it was there, the finest motorcycle quality of all at that moment. Since that time, a motorcycle being there is, of course, important, but how it goes and sounds and what it gives and how it helps you find That Feeling become more important. One’s taste just seems to, you know, escalate.

The very seamlessness and stellar performance of modern bikes still gives me That Feeling. But I’ve always liked a challenge. It’s how I’ve ended up with vintage bikes and why I am compelled to ride them on 1000-mile trips. Why bang your head against the wall with classic bikes, especially things like Velocettes, Triumphs and Nortons? Some of us are just perverts like that.

English isn’t the only way, but for me, Britbikes seem to smell right, which may be putting the cart before the horse. I had a Laverda 3CL for a number of years, and it was as thrilling and infernal as any Commando. Same with my RD350, which was wicked fun, had oil leaks and plenty of Lucas-joke-worthy electrical problems. But I keep returning to the motorcycles born on that overwatered rock in the North Sea. This is the subject of further contemplation, and if I get anywhere with it, maybe a column.

Like a moth drawn to a weak-ass flame that may flicker and go out at any moment, I repurchased my ’74 Norton 850 Commando last year, and it’s needed quite a bit of “renewing,” as the English manuals like to say. All I’ve wanted is to get it to that point where I’ve smacked down all the moles in the carnival game and no more of them pop up.

I thought I was there on my ride south from Carmel to Los Angeles this past spring. I’d had a great weekend at the Quail Motorcycle Gathering, rode the 850 on the tour with more than 100 other fantastic bikes, then got three laps around Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca with 6800-rpm upshifts, dragging hard parts and experiencing headshake entering the Corkscrew. All this without one adjustment or bit of tuning, not even tire pressure. “Maybe I’ve got it!” I thought to myself as I motored back to the hotel after a great day of riding.

Next day, when I pointed the front wheel south on Highway 1 and really got with the flow by Big Sur, I was cresting, finding That Feeling of everything coalescing. The sun was warm, the air was cool, the bike was on song like it had never been. My confidence was swelling as I sped toward that great place where my accomplishment as a mechanic, tuner and rider all harmonized on the road. All that was left was the grind on 101 South after San Luis Obispo, the freeway its own kind of satisfaction since the bike (with a threetooth-larger-than-stock 24-tooth countershaft sprocket) was cruising easily at 80 mph and delivering 55 mpg.

“Yes, I am almost there,” I thought to myself.

That Feeling was coming. It was gloriously close, just 200 miles away.

And yet, it was so far.

The bike shuddered in a deep and disturbing way, like a major earthquake in England: completely wrong.

I sat up, senses tuned to a high pitch from instant adrenaline and worry, and the bike shook again, really slowed, then made the horrible sound of a machine trying to eat itself—or at least a nice, crunchy bearing.

I shot straight to the freeway exit and coasted to the gas station conveniently located right at the end of the offramp. I was just about equidistant from Carmel and L.A., not sure which of my friends would get victimized by coming to get me roughly 200 miles from their home on a formerly peaceful Sunday.

Guilt was the first feeling after I exhaled, and not about potentially wrecking a friend’s day. The primary drive had just received a major bit of work and cleaning, and I’d also replaced some bearings and a seal in the gearbox. So I thought it was something I’d done.

Perhaps the trans had let go? But I peeked inside the gearbox, and the oil was clean and showed no signs of carnage. I went to check the primary and just about burned my fingertips off when I removed the chain-inspection cover. White smoke poured out of the hole and continued to do so for the next 10 minutes! Puzzlingly, chain tension was perfect.

After the bike cooled, I pushed it around back and pulled the primary cover (easy, with just one big bolt in the center holding it on) and discovered what had happened. The alternator rotor on the end of the crankshaft had grenaded and made so much friction with the encircling stator ring that it caused that English earthquake—and then set the resin in the stator on fire! The resulting metal bits and debris flying around behind the cover made the “bike-eats-itself” noises. But there was no apparent collateral damage.

I’m in it for the thrills, folks.

I cleaned up the mess, broke off the rest of the pieces of the rotor and refilled the primary with fresh automatic transmission fluid purchased at the gas station.

The bike kicked right to life and ran on the battery all the way home.

Since then, all has been repaired. In fact, I’ve put hundreds of miles on the bike. Just last week, after a particularly challenging day, I called my wife, Jen, and asked her to take a ride to dinner with me on the Commando at sunset.

We arced along the winding road on our way to town in late, golden sunshine on a warm evening, the bike humming below us.

That Feeling was even better when we made it home from the restaurant. I think I’m there.

Oh, that's a good one.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Roundup

RoundupConti Attack Days 2012

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Don Canet -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1987

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! Lo Rider Concept

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Blake Conner -

Rolling Concours 2012

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupA Really Big Show

SEPTEMBER 2012 By Mark Hoyer -

Interview

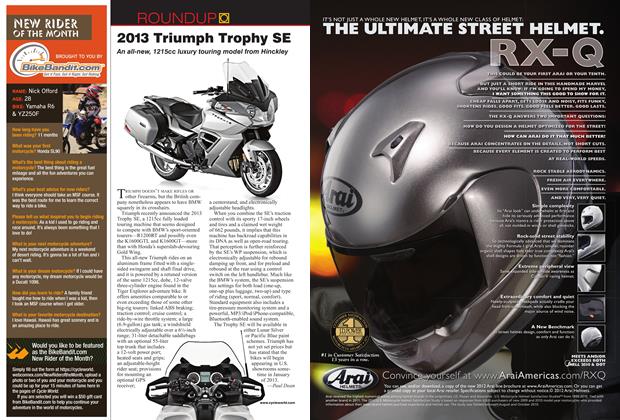

InterviewNew Rider of the Month

SEPTEMBER 2012