Building Engines

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

THIRTY-FIVE YEARS AGO I BUILT A lot of modified Yamaha RD Twins for club racers, and nobody asked me for jetting instructions because everyone did his own jetting. Times changed and club racers wanted not only specific jetting but also a guarantee that no seizure or crankshaft failure would ever occur.

Thirty-five years ago a clubman came to me after his morning practice, saying, “My crank just went, but I’ve got another.” Forty-five minutes later he came by with his engine running, having changed the crank. More recently an earnest do-it-yourselfer phoned to tell me he was planning to change the crank in his RD. He was studying the manual, ordering tools and clearing a space. He was so methodical (and inexperienced) that the job

took him a week and many phone calls. I admired his determination to master the unfamiliar, but I could also see the difference between what used to be routine and what is now considered remarkable.

Therefore, at this year’s pre-Daytona tire test, I was delighted to meet Ronnie Saner. He builds things and learns from what he does. He asked me, “Do you know Gary Robison? I learned from him.” Gary Robison has done everything and worked to understand it. I learned from him, too. Saner said, “I was trying to understand a watercraft carburetor and Gary said, ‘Just push the [expletive deleted] through the bandsaw. Then you’ll see exactly how it works. You wreck a lot less parts by cutting one up and knowing what you’re doing than if you just go ahead making the same mistake over again.’”

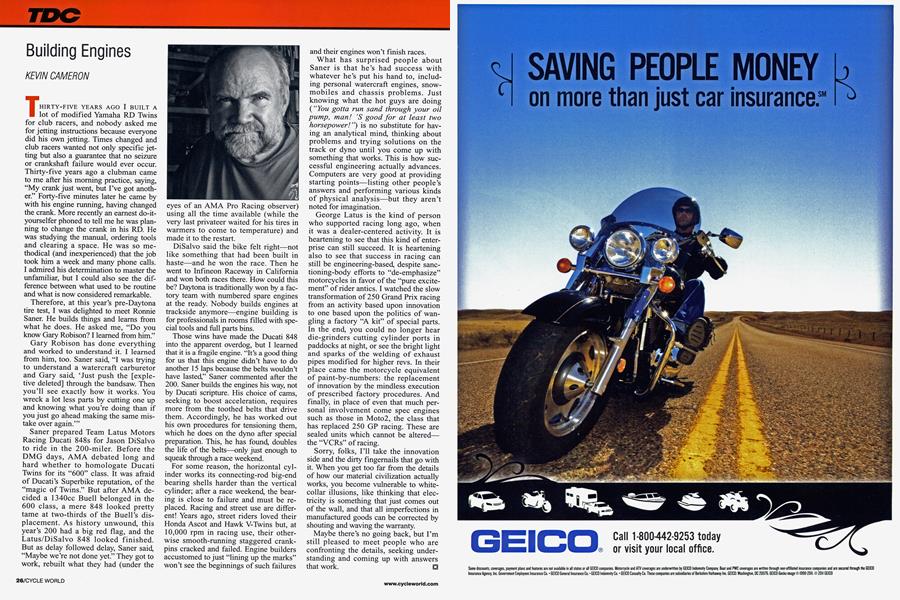

Saner prepared Team Latus Motors Racing Ducati 848s for Jason DiSalvo to ride in the 200-miler. Before the DMG days, AMA debated long and hard whether to homologate Ducati Twins for its “600” class. It was afraid of Ducati’s Superbike reputation, of the “magic of Twins.” But after AMA decided a 1340cc Buell belonged in the 600 class, a mere 848 looked pretty tame at two-thirds of the Buell’s displacement. As history unwound, this year’s 200 had a big red flag, and the Latus/DiSalvo 848 looked finished. But as delay followed delay, Saner said, “Maybe we’re not done yet.” They got to work, rebuilt what they had (under the eyes of an AMA Pro Racing observer) using all the time available (while the very last privateer waited for his tires in warmers to come to temperature) and made it to the restart.

DiSalvo said the bike felt right—not like something that had been built in haste—and he won the race. Then he went to Infineon Raceway in California and won both races there. How could this be? Daytona is traditionally won by a factory team with numbered spare engines at the ready. Nobody builds engines at trackside anymore—engine building is for professionals in rooms filled with special tools and full parts bins.

Those wins have made the Ducati 848 into the apparent overdog, but I learned that it is a fragile engine. “It’s a good thing for us that this engine didn’t have to do another 15 laps because the belts wouldn’t have lasted,” Saner commented after the 200. Saner builds the engines his way, not by Ducati scripture. His choice of cams, seeking to boost acceleration, requires more from the toothed belts that drive them. Accordingly, he has worked out his own procedures for tensioning them, which he does on the dyno after special preparation. This, he has found, doubles the life of the belts—only just enough to squeak through a race weekend.

For some reason, the horizontal cylinder works its connecting-rod big-end bearing shells harder than the vertical cylinder; after a race weekend, the bearing is close to failure and must be replaced. Racing and street use are different! Years ago, street riders loved their Honda Ascot and Hawk V-Twins but, at 10,000 rpm in racing use, their otherwise smooth-running staggered crankpins cracked and failed. Engine builders accustomed to just “lining up the marks” won’t see the beginnings of such failures and their engines won’t finish races.

What has surprised people about Saner is that he’s had success with whatever he’s put his hand to, including personal watercraft engines, snowmobiles and chassis problems. Just knowing what the hot guys are doing ( “You gotta run sand through your oil pump, man! ’S good for at least two horsepower!”) is no substitute for having an analytical mind, thinking about problems and trying solutions on the track or dyno until you come up with something that works. This is how successful engineering actually advances. Computers are very good at providing starting points—listing other people’s answers and performing various kinds of physical analysis—but they aren’t noted for imagination.

George Latus is the kind of person who supported racing long ago, when it was a dealer-centered activity. It is heartening to see that this kind of enterprise can still succeed. It is heartening also to see that success in racing can still be engineering-based, despite sanctioning-body efforts to “de-emphasize” motorcycles in favor of the “pure excitement” of rider antics. I watched the slow transformation of 250 Grand Prix racing from an activity based upon innovation to one based upon the politics of wangling a factory “A kit” of special parts. In the end, you could no longer hear die-grinders cutting cylinder ports in paddocks at night, or see the bright light and sparks of the welding of exhaust pipes modified for higher revs. In their place came the motorcycle equivalent of paint-by-numbers: the replacement of innovation by the mindless execution of prescribed factory procedures. And finally, in place of even that much personal involvement come spec engines such as those in Moto2, the class that has replaced 250 GP racing. These are sealed units which cannot be altered— the “VCRs” of racing.

Sorry, folks, I’ll take the innovation side and the dirty fingernails that go with it. When you get too far from the details of how our material civilization actually works, you become vulnerable to whitecollar illusions, like thinking that electricity is something that just comes out of the wall, and that all imperfections in manufactured goods can be corrected by shouting and waving the warranty.

Maybe there’s no going back, but I’m still pleased to meet people who are confronting the details, seeking understanding and coming up with answers that work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2011

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

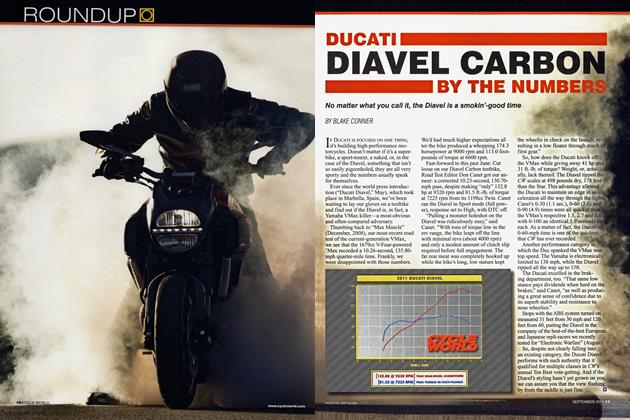

RoundupDucati Diavel Carbon By the Numbers

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

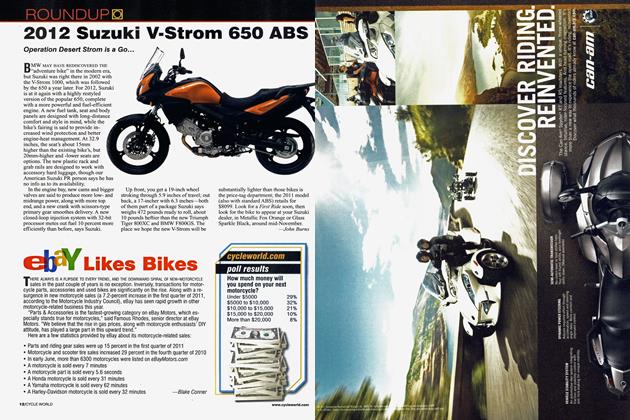

Roundup2012 Suzuki V-Strom 650 Abs

SEPTEMBER 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

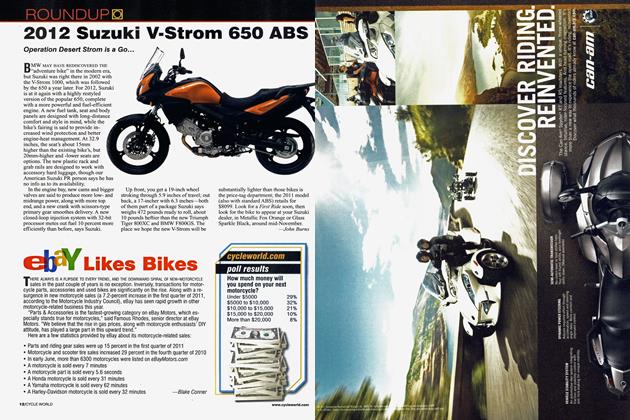

RoundupEbay Likes Bikes

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1986

SEPTEMBER 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupMv Agusta F3

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato