Balance of Power

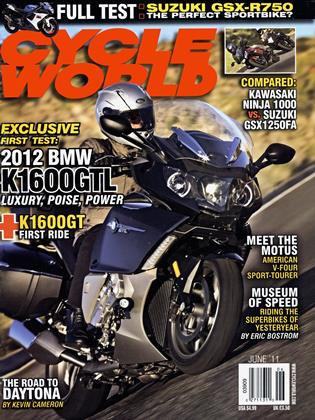

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Suzuki GSX-R750 returns to its roots

MARC COOK

IF NOT FOR THE ECONOMIC HARDSHIPS OF THE past two years, this amazing GSX-R750 might have marked the 25th anniversary of Suzuki’s iconic sportbike. It would have been an emphatic reminder that this modest manufacturer had taken sport motorcycling on an uncharted path with the original GSX-R750. Circa 1985 (’86 in the U.S.), the GSX-R brought unprecedented

features to the class—unbelievably low weight, frantic (and enthralling) high-rpm horsepower and unflinching, hard-core sporting focus. It was a Glock unholstered during a knife fight, thrust into the mid-1980s world of hefty Honda Interceptors, steel-framed Ninja 900Rs and chunky-but-powerful Yamaha FZs by a smiling but fearsomely driven mid-career engineer.

That would be Etsuo Yokouchi, inarguably the father of the GSX-R and, you could say, of sportbiking as we know it. We can thank him for that, sure, but it’s also gratifying to see his design logic prevail in the 2011 GSX-R750 (and the equally new GSX-R600). His view was that reducing mass brings far more benefit than simply increasing power. Of course, all good designers understand that “light makes right,” but it was Yokouchi’s persistence with his engineers and his salesmanship with management that got it done. Those with knowledge of the events say that probably no one else inside Suzuki would have succeeded.

As a predecessor to the 750, Yokouchi’s GSX-R400 used an inlineFour in an aluminum frame to come in 18 percent lighter than comparable

400s. He reasoned that similar weight savings could be applied to bigger machines, so the goal became straightforward: undercut existing 750s by 20 percent while maintaining the 100 PS (98.6 horsepower) voluntary power limit then in place. By Yokouchi’s decree: target weight, 176 kilograms (384 pounds).

It’s an old story now, but Yokouchi and his staff achieved their goal by simple yet exhaustive study of every part on the motorcycle. Engine, frame, suspension, running gear, bodywork— each piece came under close scrutiny. Can we make this part lighter? If liquid cooling is good, why can’t we make fluid already in the engine—lubricating oil—do double duty?

That GSX-R750 set a new standard for low mass and kicked off the supersport, racer-replica subset of sportbikes. It was

a motorcycle that Suzuki milked for reputation and racing success. And sales, as well. So, it’s usually the model Suzuki develops first and most thoroughly.

Which brings us to 2011 and a thoughtfully revised—if not credibly all-new— GSX-R750. It embraces the core values of the original: minimize weight, maximize power. We’ve heard this before, but now a new twist emerges: Suzuki has decided to boost sales of the 750 by pricing it just $400 above the 600. In 2009, there was a $1300 spread, and it had been even greater in previous years, placing the 750 perilously close in sticker to the 1000, with predictable results: GSX-R 1000s everywhere, but 750s ridden by a select few guys with less to prove.

Even if Suzuki goes to 750cc battle with only itself, the weapon is formidable. While leaving the engine to minor

updates centered on improving low-end and midrange power, the engineering staff picked over the bones of the 2009 GSX-R750 (due to the aforementioned economic meltdown, there was no 2010 model) to find excess material. The stated goal was a substantial weight reduction and improvement in handling—to make an already impressively light sportbike feel smaller and nimbler yet. According to Suzuki, the 750 lost 17 pounds—the curb weight is claimed to be 419 lb., which translates to 394 on the CW scales with the bike ready to ride but the fuel tank empty. How did the hacksaw men from Hamamatsu manage this? Just as Yokouchi and his staff did. For example, the aluminum-alloy frame (mostly cast but with a few welded-in extrusions remaining) is credited with a reduction of 2.9 pounds. Its overall geometry is the same—rake and trail remain 23.5 degrees and 97mm—but the swingarm pivot is pulled forward slightly to reduce wheelbase 0.6 inch. A new set of cast-

ings, now three pieces instead of five, results in a swingarm the same length as before but 1.9 pounds lighter. A 3degree rotation of the engine, moving the cylinder head aft, and a relocation of the Engine Control Module to just behind the steering stem help improve mass centralization, says Suzuki. Thinner exhaust head pipes (1.0mm vs. 1.2mm) cut 2.6 pounds.

These modifications reduce heft but don’t significantly alter handling, so there were a few more moves to improve the GSX-R750’s reflexes and shed a few ounces. A Showa Big Piston Fork is said to trim 2.2 pounds, which we’ll take on Suzuki’s word, but we can say that its action over cobbly California roads, more pocked than ever from a wet winter, is exemplary. Both ends of the GSX-R present as firmly sprung and damped, but the small-bump compliance is just shy of amazing. You get an unfiltered report of what both ends are doing without a hint of harshness. No lost mo-

tion. Moreover, the 750 has beautifully neutral steering, with low effort and no tendency to bump steer. It turns in smartly, on the brakes or off.

Suzuki swapped Nissin for Brembo this year, partly to reduce weight (almost a pound total). On the street, the Monobloc calipers grip the 310mm full-floating discs with just the right combination of aggressiveness and feedback; finding the threshold of traction is easy. Road Test Editor Don Canet reported from the introduction at Barber Motorsports Park that “the only issue I had (with both bikes) was the front brake lever travel would increase noticeably after about four to five hard laps. Setting the lever in #1 or #2 position kept it from pulling back to my knuckles. The stopping power was still there but it’s a bit unnerving when the feel isn’t consistent. Suzuki engineers said they selected a pad compound that performs at a high

level for the street and doesn’t

cause brake squeal.” So, if you’re racing or riding in the A group at track days, try dropping in different pads.

By slimming the 750, Suzuki has narrowed the gap in feel to the 600 but not quite closed it. Canet says that “both bikes handled very well with excellent stability on the brakes and throughout the corner. Back to back, the 600 feels slightly more agile, as to be expected, but not so much to sway my preference for the 750 and its added power.”

It hasn’t always been this close; in fact, until this generation, the 600 typically held the finesse advantage. For many riders, the added torque of the 750 didn’t quite offset the ever-so-slightly dulled reflexes.

That should change, though it’ll take jumping from the 750 onto the 600 to fully appreciate the bigger bike. Where a 600 needs clutch-singeing revs off the line, the GSX-R750 is happy to ride a stout torque curve; check out the dyno chart. Our 2011 testbike produced the same peak numbers as the last GSX-R750 we tested, a 2008 model—127 horsepower and 55 foot-pounds of torque—but no apparent change in the low-end and midrange.

But that’s not the point of this 750-to600 comparison. Take a look at your typical 600 supersport’s dyno chart and you’ll see that the torque curve seldom goes above 40 ft.-lb. until 9000 rpm or so, and it then peaks around 42-44 ft.-lb. The GSX-R750’s torque curve crosses the 40 ft.-lb. mark way down at 4750 rpm and exceeds 50 from 8000 all the way to 13,000 rpm. That’s torque you can feel and use. Every day.

Greater bottom-end makes the GSX-R750 easier to live with day-today, as do changes in Suzuki’s S-DMS (Drive Mode Selector), which now has two settings instead of three. The A mode is full power, maximum throttle response. B mode is softer than even the C mode was for the 2009 bike. It’s useful for keeping pace on slippery pavement, but the A mode’s throttle response is so good and so predictable that the softer map is not a must-have feature.

Could the GSX-R, long the bad boy among sportbikes, be going soft? After all, the bars have been angled outward (as viewed from the saddle) for a slightly more relaxed riding position; the seat is the lowest in the class; the fuel tank is

reshaped to move the rider forward (to counteract the torque and short wheelbase); and the footpegs are three-way adjustable. Flour on the countertop doesn’t make a cake, so let’s not jump to conclusions.

No, it’s better to say that the GSX-R750 has shaded back toward its roots this year, as it has done on previous occasions—1996 and 2000 were watershed years, after strict diets and a few months at the health club. What Mr. Yokouchi understood and so believed in as he helped push the first GSX-R through a stolid, grindingly careful corporation is that performance should be balanced, neither handling nor power should dominate, and that low weight makes the balance easier to find.

Here in the new GSX-R750 is rousing validation of his philosophy. A 26th Anniversary special, you might say. □

At Cycle Guide when the GSX-R made its 1986 U.S. debut, Cook got the opportunity to interview most of the original engineers, including Mr. Yokouchi, for his 2005 book, Suzuki GSX-R: A Legacy of Performance.

EDITORS' NOTES

G`X-Rs are so popular that my punk,

“anti” side wanted to hate on them. Mat Mladin this, Ben Spies that—Suzuki has won 10 out of the last 12 AMA Superbike titles. Going against the grain, I asked myself, What does this mean to the road rider?

But the GSX-R750 started to overturn my predisposition before I even hit the starter button for the mid-cc-sized engine. It comes so lightly off its kickstand. That carbonesque-patterned plastic seat cowl is sweet. Couldn’t help but like the Yin/Yang, black/white color change accentuating the side of the new newly reshaped seat section’s bodywork.

And in the saddle? Recent rain made for sediment-strewn roads and some loose traction. Thanks to the GSX-R750’s balanced chassis, linear power and the Brembo braking touch, I had the confidence to operate its Bridgestones at their grip boundaries.

So, that’s what race experience does for GSX-R riders.

—Mark Cernicky, Associate Editor

I suspect Suzuki will face a tough challenge selling many of its all-new GSX-R600 sportbikes here in America this year. I only say this due to its sibling rivalry with the GSX-R750, now priced at a mere $400 more.

I spent an entire day riding both 600 and 750 versions of the 2011 GSX-R during the U.S. press introduction staged at Barber Motorsports Park, where it was clearly apparent which of Suzuki’s supersport duo offers the most value, performance and practicality for all but those looking to race in sanctioned 600cc competition.

The 750 provides a notable performance boost throughout the entire rev range that makes it a more flexible and enjoyable streetbike in every way. Its weight loss claim is for real, and the bike tipping our scale under 400 pounds has certainly impressed me.

The way I see it is this: If you’re in for a penny you may as well be in for a pound. It will be the best $400 one could ever spend.

—Don Canet, Road Test Editor

I own and remain in love with a 2005 GSX-R750, a 20th Anniversary edition, even. When I rode updated ’06 and ’08 machines, I was relieved that they weren’t massively better. My investment seemed sound.

Until this year. Despite what seem like small updates, the 2011 GSX-R750 is a dramatically better bike than my ancient blue-white-black mule. That pumped-up low-end is shockingly useful, and the intake growl makes loud pipes even more of a bad idea. Small stuff compared to the improvements in suspension and steering. The new bike is (and feels) lighter, far more taut and agreeably compact. My ’05 seems like a bus.

I don’t intend ever to sell my GSX-R. Having the good fortune of interviewing most of Suzuki’s engineers and Mr. Yokouchi for a book on the model, I feel a little closer to the family, and so my 750 is something more than a motorcycle to me. But I can’t say my eye hasn’t just wandered. —Marc Cook, Contributing Editor

SUZUKI

$11,999

GSX-R750

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA Japan In Need

JUNE 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAmerican Sport-Tourer

JUNE 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

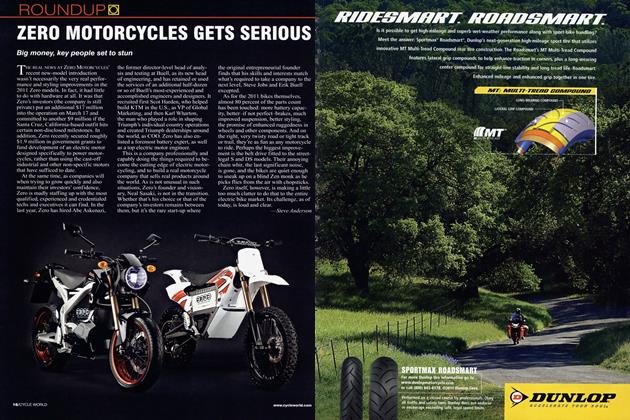

RoundupZero Motorcycles Gets Seriou

JUNE 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupA Leaning Spyder?

JUNE 2011 By Steven L. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupMax Respect

JUNE 2011 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

RoundupBurgman Fuel Cell Scooter For Real

JUNE 2011 By John Burns