One Man's Island

LEANINGS

PETER EGAN

WINTER DROPPED ON THE MIDWEST like an anvil this past week while I was working at our office in California, and I flew home to a Wisconsin that had changed from autumn brown to solid white. The late afternoon sky had a winter purple cast, giving the snow a luminous midnight-in-Lapland quality. I’d changed our car over to its winter tires— made, appropriately, in Finland—right before I left, so it was tracking nicely down the hard-packed snow to our house.

Riding season was clearly over. Time to remove the bike batteries for charging and admit that book and video season had arrived. Vicariousness R Us.

And—as luck would have it—I sat down in my office the next day and remembered that I just happened to have both an intriguing book and a DVD floating somewhere near the top of the chaos pile on my desk, long overdue for a closer inspection.

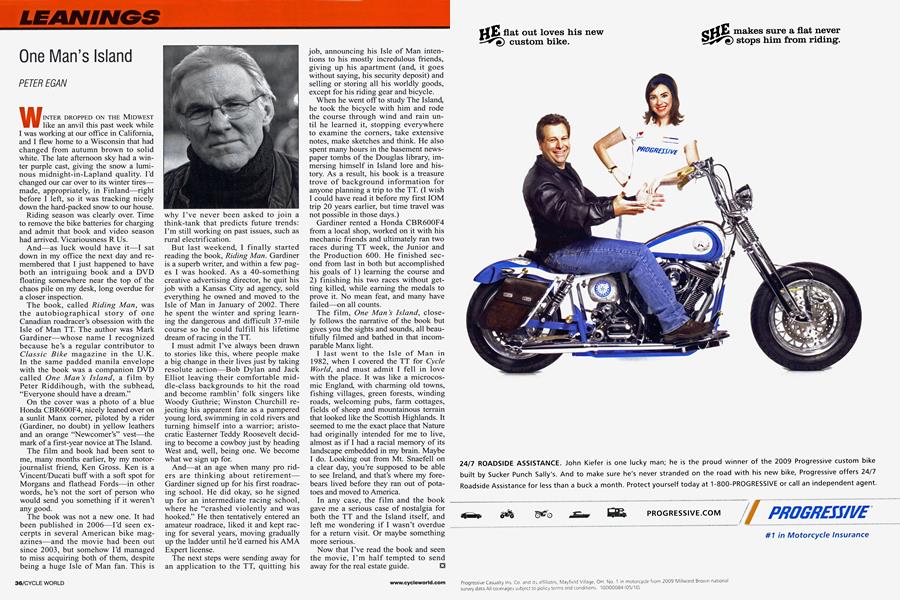

The book, called Riding Man, was the autobiographical story of one Canadian roadracer’s obsession with the Isle of Man TT. The author was Mark Gardiner—whose name I recognized because he’s a regular contributor to Classic Bike magazine in the U.K. In the same padded manila envelope with the book was a companion DVD called One Man ’s Island, a film by Peter Riddihough, with the subhead, “Everyone should have a dream.”

On the cover was a photo of a blue Honda CBR600F4, nicely leaned over on a sunlit Manx comer, piloted by a rider (Gardiner, no doubt) in yellow leathers and an orange “Newcomer’s” vest—the mark of a first-year novice at The Island.

The film and book had been sent to me, many months earlier, by my motorjournalist friend, Ken Gross. Ken is a Vincent/Ducati buff with a soft spot for Morgans and flathead Fords—in other words, he’s not the sort of person who would send you something if it weren’t any good.

The book was not a new one. It had been published in 2006—I’d seen excerpts in several American bike magazines—and the movie had been out since 2003, but somehow I’d managed to miss acquiring both of them, despite being a huge Isle of Man fan. This is why I’ve never been asked to join a think-tank that predicts future trends: I’m still working on past issues, such as rural electrification.

But last weekend, I finally started reading the book, Riding Man. Gardiner is a superb writer, and within a few pages I was hooked. As a 40-something creative advertising director, he quit his job with a Kansas City ad agency, sold everything he owned and moved to the Isle of Man in January of 2002. There he spent the winter and spring learning the dangerous and difficult 37-mile course so he could fulfill his lifetime dream of racing in the TT.

I must admit I’ve always been drawn to stories like this, where people make a big change in their lives just by taking resolute action—Bob Dylan and Jack Elliot leaving their comfortable middle-class backgrounds to hit the road and become ramblin’ folk singers like Woody Guthrie; Winston Churchill rejecting his apparent fate as a pampered young lord, swimming in cold rivers and turning himself into a warrior; aristocratic Easterner Teddy Roosevelt deciding to become a cowboy just by heading West and, well, being one. We become what we sign up for.

And—at an age when many pro riders are thinking about retirement— Gardiner signed up for his first roadracing school. He did okay, so he signed up for an intermediate racing school, where he “crashed violently and was hooked.” He then tentatively entered an amateur roadrace, liked it and kept racing for several years, moving gradually up the ladder until he’d earned his AMA Expert license.

The next steps were sending away for an application to the TT, quitting his job, announcing his Isle of Man intentions to his mostly incredulous friends, giving up his apartment (and, it goes without saying, his security deposit) and selling or storing all his worldly goods, except for his riding gear and bicycle.

When he went off to study The Island, he took the bicycle with him and rode the course through wind and rain until he learned it, stopping everywhere to examine the corners, take extensive notes, make sketches and think. He also spent many hours in the basement newspaper tombs of the Douglas library, immersing himself in Island lore and history. As a result, his book is a treasure trove of background information for anyone planning a trip to the TT. (I wish I could have read it before my first IOM trip 20 years earlier, but time travel was not possible in those days.)

Gardiner rented a Honda CBR600F4 from a local shop, worked on it with his mechanic friends and ultimately ran two races during TT week, the Junior and the Production 600. He finished second from last in both but accomplished his goals of 1) learning the course and 2) finishing his two races without getting killed, while earning the medals to prove it. No mean feat, and many have failed—on all counts.

The film, One Man ’s Island, closely follows the narrative of the book but gives you the sights and sounds, all beautifully filmed and bathed in that incomparable Manx light.

I last went to the Isle of Man in 1982, when I covered the TT for Cycle World, and must admit I fell in love with the place. It was like a microcosmic England, with charming old towns, fishing villages, green forests, winding roads, welcoming pubs, farm cottages, fields of sheep and mountainous terrain that looked like the Scottish Highlands. It seemed to me the exact place that Nature had originally intended for me to live, almost as if I had a racial memory of its landscape embedded in my brain. Maybe I do. Looking out from Mt. Snaefell on a clear day, you’re supposed to be able to see Ireland, and that’s where my forebears lived before they ran out of potatoes and moved to America.

In any case, the film and the book gave me a serious case of nostalgia for both the TT and the Island itself, and left me wondering if I wasn’t overdue for a return visit. Or maybe something more serious.

Now that I’ve read the book and seen the movie, I’m half tempted to send away for the real estate guide. n

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIboty

APRIL 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupDakar 2011, Street's View

APRIL 2011 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley-Davidson Blackline Fxs

APRIL 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Victory High Ball

APRIL 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago April 1986

APRIL 2011 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupDisaster Averted

APRIL 2011 By Kevin Cameron