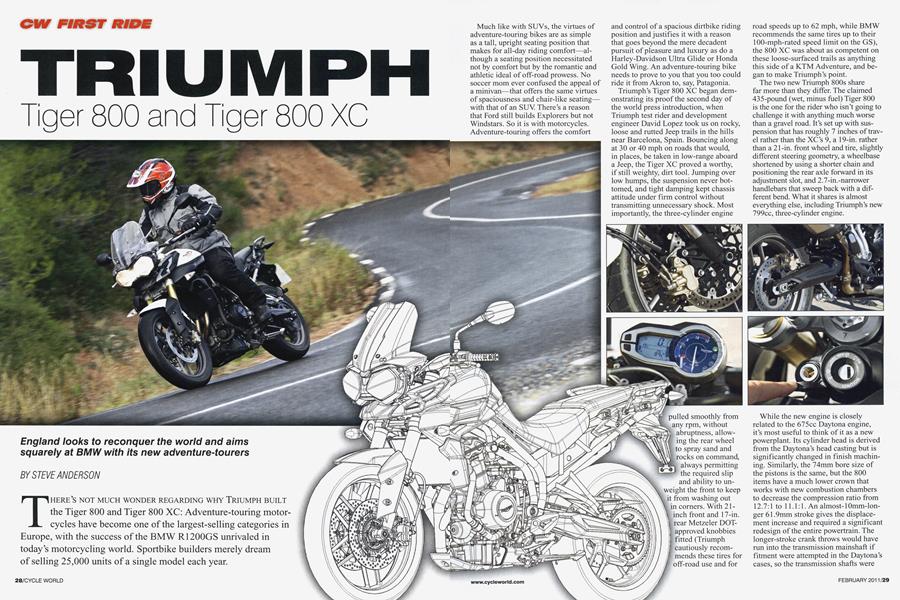

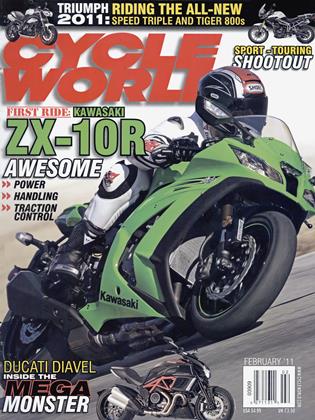

TRIUMPH Tiger 800 and Tiger 800 XC

CW FIRST RIDE

England looks to reconquer the world and aims squarely at BMW with its new adventure-tourers

STEVE ANDERSON

THERE'S NOT MUCH WONDER REGARDING WHY TRIUMPH BUILT the Tiger 800 and Tiger 800 XC: Adventure-touring motorcycles have become one of the largest-selling categories in Europe, with the success of the BMW R1200GS unrivaled in today’s motorcycling world. Sportbike builders merely dream of selling 25,000 units of a single model each year.

Much like with SUVs, the virtues of adventure-touring bikes are as simple as a tall, upright seating position that makes for all-day riding comfort—although a seating position necessitated not by comfort but by the romantic and athletic ideal of off-road prowess. No soccer mom ever confused the appeal of a minivan—that offers the same virtues of spaciousness and chair-like seating— with that of an SUV There’s a reason that Ford still builds Explorers but not Windstars. So it is with motorcycles. Adventure-touring offers the comfort and control of a spacious dirtbike riding position and justifies it with a reason that goes beyond the mere decadent pursuit of pleasure and luxury as do a Harley-Davidson Ultra Glide or Honda Gold Wing. An adventure-touring bike needs to prove to you that you too could ride it from Akron to, say, Patagonia.

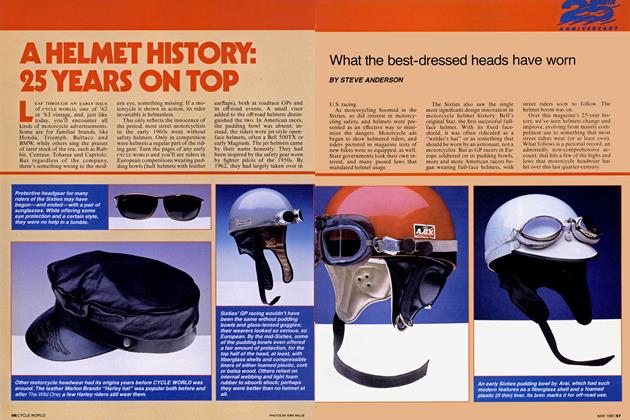

Triumph’s Tiger 800 XC began demonstrating its proof the second day of the world press introduction, when Triumph test rider and development engineer David Lopez took us on rocky, loose and rutted Jeep trails in the hills near Barcelona, Spain. Bouncing along at 30 or 40 mph on roads that would, in places, be taken in low-range aboard a Jeep, the Tiger XC proved a worthy, if still weighty, dirt tool. Jumping over low humps, the suspension never bottomed, and tight damping kept chassis attitude under firm control without transmitting unnecessary shock. Most importantly, the three-cylinder engine pulled smoothly from any rpm, without abruptness, allowing the rear wheel to spray sand and rocks on command, always permitting the required slip and ability to unweight the front to keep it from washing out in corners. With 21inch front and 17-in. rear Metzeier DOTapproved knobbies fitted (Triumph cautiously recommends these tires for off-road use and for road speeds up to 62 mph, while BMW recommends the same tires up to their 100-mph-rated speed limit on the GS), the 800 XC was about as competent on these loose-surfaced trails as anything this side of a KTM Adventure, and began to make Triumph’s point.

The two new Triumph 800s share far more than they differ. The claimed 435-pound (wet, minus fuel) Tiger 800 is the one for the rider who isn’t going to challenge it with anything much worse than a gravel road. It’s set up with suspension that has roughly 7 inches of travel rather than the XC’s 9, a 19-in. rather than a 21 -in. front wheel and tire, slightly different steering geometry, a wheelbase shortened by using a shorter chain and positioning the rear axle forward in its adjustment slot, and 2.7-in.-narrower handlebars that sweep back with a different bend. What it shares is almost everything else, including Triumph’s new 799cc, three-cylinder engine.1

While the new engine is closely related to the 675cc Daytona engine, it’s most useful to think of it as a new powerplant. Its cylinder head is derived from the Daytona’s head casting but is significantly changed in finish machining. Similarly, the 74mm bore size of the pistons is the same, but the 800 items have a much lower crown that works with new combustion chambers to decrease the compression ratio from 12.7:1 to 11.1:1. An almost10mm-longer 61.9mm stroke gives the displacement increase and required a significant redesign of the entire powertrain. The longer-stroke crank throws would have run into the transmission mainshaft if fitment were attempted in the Daytona’s cases, so the transmission shafts were moved a few millimeters—requiring a new crankcase casting and primarydrive gears. The new cases, unlike those of the 675, also include a swingarm pivot mount. Because an adventure bike is expected to run numerous high-draw electrical accessories (heated grips, electric clothing, auxiliary lights, etc.), a big and expensive rare-earth-magnet alternator was fitted to the left end of the crank, capable of pumping out fully 645 watts—significantly more than the output of the 400-watt F800GS, though not quite as high as the R1200GS and its 720 watts. The crankshaft with its longer throws and the big alternator both work to increase the engine’s flywheel effect, helping to change its character from the sharp, quick-revving nature of the 675cc mill to something a little more relaxed and slower-responding. Similarly, the engine tune was changed completely with new shorter-duration camshafts and very short intake/exhaust overlap, turning the engine from a complete revver to a lugger. In the end, the 800 shares only 15 percent of its com-

ponents with the 675.

Upon first ride, you can tell the new engine is a sweetheart. It pulls hard from 1500 rpm in top gear and even harder in its midrange, with power climbing smoothly so that it’s easy to run it into its 9800-rpm rev-limiter. It’s a chameleon of an engine—run it in fourth and fifth gear on a tight, twisty road and it’s relaxed and profoundly vibration-free, rewarding momentum and smoothness, but making you do the braking. Change down to first and second on the same road, and it becomes a high-rpm charger, accelerating fiercely and with enough engine braking to allow you to largely forget about the rear brake. If you’re keeping it working hard between 8000 and 9800 rpm, for the first time it starts to feel slightly buzzy—more a sensation than a complaint, as the vibration never ventures into real rider discomfort. The fueling is precise enough that if you’re riding in the last 20 percent of the rev range, it’s still easy to dial in just a little throttle at corner entry to negate the engine braking and balance the chassis. With a claimed 94 hp, the 800 is the class leader of the midsize adventure segment.

The gearbox shifts readily and easily. Initial launch requires just slight finesse with the clutch; killing the engine on initial takeoff proved a little too easy, often requiring just a little more clutch slip or throttle than it should. But once moving, you often have a choice of any of the six gears to run in. Do you want 30 mph in first, busy but with hard acceleration a throttle twitch away? Have at it. Or sixth, serene but with snatchfree-if-somewhat-glacial acceleration? Your choice.

Off-road capability and two-up handling figured strongly in the chassis design from the beginning. Both machines stretch out on long wheelbases,

61.2 in. and 61.7 for the 800 and 800 XC, respectively. Weight distribution is nearly 50/50 on each, with the long wheelbase diminishing the effect of weight shift when adding a passenger or luggage. Even the choice of frame material—steel—is claimed to meet adventure-touring needs. “If you ever happen to break a frame somehow in the South American outback,” says Triumph Motorcycle Product Manager Simon Warburton, “you know you can find someone to stick a steel frame back together. Just try that with aluminum!”

The main difference between the two chassis are the suspension components: The XC comes with a 45 mm fork offering 8.6 in. of wheel travel, while the standard 800 gets a smaller 43mm fork with 7.1 in.

At the back, the wheels travel 8.5 and

6.7 in., respectively. And those wheels are considerably different. The standard version gets cast rims in 19and 17-in. sizes fitted with Pirelli Scorpion Sync tires, while the XC gets wire spokes with high-strength aluminum rims ina21/17in. combination, fitted with tube-type Bridgestones. Steering geometry was optimized for both bikes by giving their respective forks slightly different tubecenterline-to-axle offsets. In either case, the steering geometry is fairly steep: 23.1 degrees and 3.6 inches trail on the XC;

23.7 and a mere 3.4 on the standard.

The small differences in geometry and the big ones in the tires make a world of difference in handling feel. The standard bike is light-steering to a near fault, requiring almost scooter-level effort. The XC, in contrast, with more trail and an extra 2-lb.-plus of front wheel, tire and tube mass concentrated near a larger outer diameter, requires higher effort but telegraphs front tire traction feel superbly. At the press introduction, one day was spent on each bike and, as the low-asperity Spanish road surfaces were frequently wet and noticeably slippery on the day riding the standard model, final handling judgment will have to wait for longer rides under more ideal conditions. But on at least an initial basis, there’s a strong preference for the XC.

“With 21-in. front and 17-in. rear Metzeler DOTapproved knobbies fitted, the 800 XC was about as competent on these loose-surfaced trails as anything this side of a KTM Adventure.”

The ergonomic differences between the two bikes are concentrated at the handlebars. The XC comes with winddeflecting handguards, a nice touch in cool conditions (these are optional for the 800). The handlebar clamps on both bikes are asymmetrical, designed to allow the bars to be moved forward 20mm if reversed. In addition, the XC bar clamps are essentially risers, allowing a relatively wide and flat bar with only minimal sweepback to be fitted, a bar that can be readily rotated to find a position that works both sitting and standing in off-road use. In addition, both machines have rider’s seats that can be in either a low or high position (about an inch difference) in seconds with no tools beyond the ignition key (31.9 or

32.7 on the 800 and 32.2 or 34.0 on the XC). A yet-lower, gel-type seat will be optionally available immediately, and an inch-taller seat is planned as a second-year accessory. In either case, the machines offer a comfortable riding position, the 800 standard with the seat in the low position unlikely to intimidate shorter riders.

Along with the motorcycles, Triumph also announced a substantial line of accessories for the 800s that will be available immediately. Along with the aforementioned low seat, side and top boxes, various tail and tankbags, a centerstand, auxiliary lights, engine-protection bars and a sump guard can be ordered from a Triumph dealer with the motorcycle. The large accessory range tells how seriously Triumph is taking this motorcycle. Initial planning centered around selling 5000 800s per year worldwide. But, as the company has had more experience with these machines and heard back from its national distributors, it now plans to increase that to 7500 units per year, with a mix of about 55/45 percent Tiger 800 XCs to Tiger 800s. It’s an ambitious plan, but the motorcycle is good enough that even 7500 800s a year may prove pessimistic. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe “last” Rebuild

FEBRUARY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

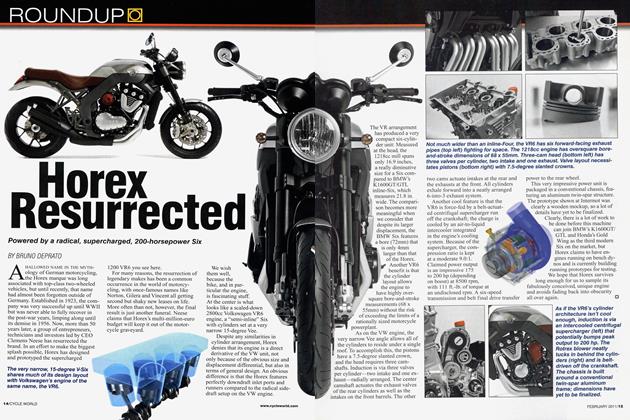

Roundup

RoundupHorex Resurrected

FEBRUARY 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Ducati Superbike

FEBRUARY 2011 By Jeff Roberts -

Roundup

RoundupLittle Hauler

FEBRUARY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1985

FEBRUARY 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

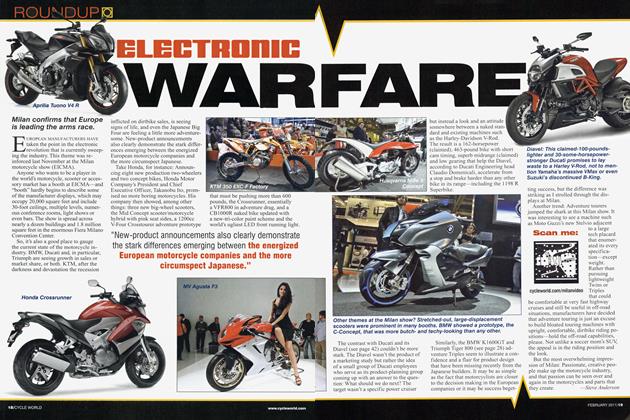

RoundupElectronic War Fare

FEBRUARY 2011 By Steve Anderson