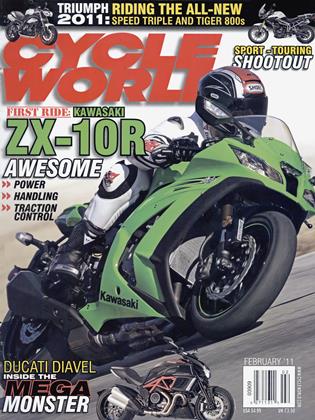

Ducati Diavel

Dancing with the devil

STEVE ANDERSON

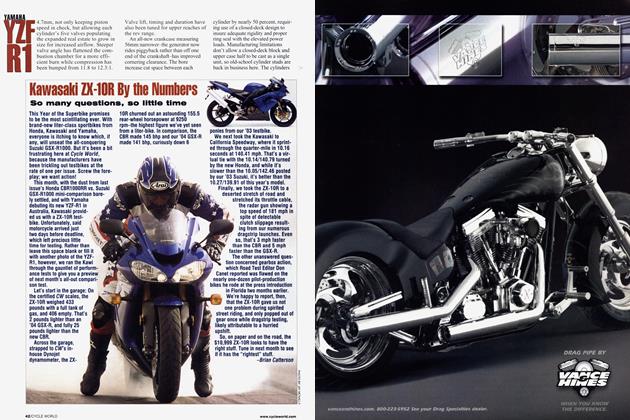

DUCATI'S DIAVEL IS DEFINED BY WHAT IT ISN’T. IT ISN’T A power cruiser, at least not as has been previously known. A Harley-Davidson V-Rod Muscle, for example, scales in at about 670 pounds wet and, with about 110 horespower at the rear wheel, has a power-to-weight ratio of 6.1 lb. per hp. The latest

Star VMax’s 701 lb. weight fairly crushes the earth, so even its 174 hp barely lifts its power-to-weight ratio to 4.0 lb./hp, far from Open-class sportbikes. In contrast, the Diavel Carbon—the more-expensive $ 19,995 model with carbon-fiber parts and forged wheels (vs. the $16,995 standard version)—is claimed to weigh just 457 lb. dry and to make 162 horses at the crank. Based on past his^ tory, those numbers will likely translate Ik \ into a full-up wet weight of around i 502 lb. and a CW dyno result of aroun<^ 145 hp. That’s fully 168 lb. lighter than the V-Rod and 199 less than the VMax. At 3.5 lb./hp, ' the Diavel will boast a power-toweight ratio which just a few years * r ago would have been good for an \ ^ Open-class, four-cylinder superbike.

But with a 62.3-inch wheelbase, the Diavel is also long and low compared to any superbike and has the shortest gearing of any Ducati with the 1198 engine. It’s little wonder, then, that Project Leader Giulio Malagoli can say that the Diavel accelerates harder off the line than an 1198R and brakes harder, too. Both are limited by wheel lift on the shortwheelbase superbike. Ducati is claiming a 0-60-mph time of around 2.5 seconds, which would make the Diavel one of the quickest bikes—if not the quickest—in mass production.

But in styling, the Diavel is more power cruiser than naked standard or streetfighter, the other categories in which the compulsive cataloger might place it. Its fuel tank is long to begin with, then visually lengthened with functional air scoops that extend past the fork tubes; they’re slightly reminiscent of the scoops on both the VMax and the latest V-Rod Muscle. The elliptical headlight—striped with LED parking lights—and swoopy flyscreen above it also hark back to classic motorcycles.

Ducati Operating Manager Claudio Domenicali points out that the intent from the beginning was to build a bike with its visual mass forward, with an enormous rear tire connoting power and the airy tail of a short-circuit racer or dirt-tracker. This is, interestingly enough, the same visual combination that Erik Buell arrived at by studying pictures of classic racebikes that

had strong visual appeal, and that helped shape the original Buell S1 Lighting. “A muscular silhouette.. .that looks like a power athlete on the starting blocks...

the front wheel kept close to the Diavel’s body and the short tail of a sportbike,” explains Ducati Design. “Lateral radiators adding muscle to its broad ‘shoulders,’ which then taper down across the engine and into the belly fairing with oil cooler...” Whatever the Diavel may look like, though, Ducati kept the footpegs under the rider, rather than in a more foot-forward, cruiser riding position.

Domenicali describes the percentage balance between design and engineering on the Diavel as 60/40, respectively, rather than the 40/60 it might be on a superbike. He also says that the machine is designed to bridge the naked-sportbike and power-cruiser classes. There are certainly design elements—such as the pointy, cool-looking and non-functional handlebar clamp extensions—that clearly indicate the industrial design team had more leeway than it might have on a bike that had to scale in at 380 lb. A number of design solutions are particularly elegant, such as the side-mounted radiators with elaborate and very refined-looking ducts directing air from inside to out.

One personal note: Having spent two racing seasons searching for the optimum cooling system for Buell 1125-based racebikes with similarly positioned radiators, using extensive CFD-modeling and wind-tunnel and track testing as tools,

I can confidently say the Ducati sidemounted radiators will almost certainly cool like gangbusters and may even do a good job of keeping hot air off the rider’s legs. But the aerodynamic drag imposed by pushing the radiator flow out the sides would never be acceptable for a superbike. This latter point, of course, will not be a concern for a bike that’s limited by gearing to about 150 mph.

One other thing the Ducati insiders intimate: The Diavel handles, 240mm rear tire or no. According to Malagoli, that was his biggest concern when the project began but rapidly went away as early prototypes showed handling—with the newly designed Pirelli 240/45R17 tire profiled similarly to a MotoGP tire— simply wasn’t an issue. “You ride the bike for 100 meters,” says Malagoli, “and you know it’s right.” The machine was designed around a 41-degree lean angle with the suspension two-thirds compressed, the same as on the 696 Monster.

Of course, the electronically obsessed will find much to like in the Diavel, from the standard ABS and traction control to the electronic throttle to the dual-level LCD instruments to the keyless ignition. This machine is a rolling advertisement for how far motorcycle electronics have come. Similarly, the mechanical parts are smack for the hardware-addicted: The 8-in.-wide Enkei rear wheel on the standard Diavel has a roll-formed rim for near-forged material properties, allowing it to weigh just 11 lb. Its braking hardware uses exactly the same Brembo Monobloc calipers as on the 1198 Superbike. The engine cases are a super-high-vacuum, low-porosity die-casting that increases strength and saves pounds over conventional casting technology.

So, how about this: The Diavel fits nowhere. It’s a new Ducati that offers something for everyone—handling, unique looks, performance, gadgetry, etc.—in a package never before seen. Whether or not it finds the customers Ducati wants probably has more to do with its singular styling than anything else, but that’s not because Ducati hasn’t built an apparently kick-ass motorcycle. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe “last” Rebuild

FEBRUARY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

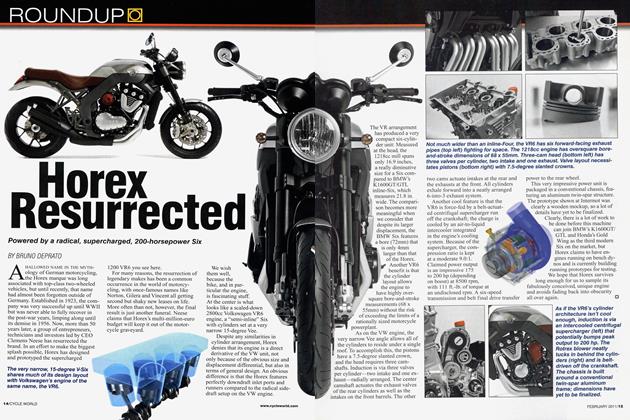

RoundupHorex Resurrected

FEBRUARY 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Ducati Superbike

FEBRUARY 2011 By Jeff Roberts -

Roundup

RoundupLittle Hauler

FEBRUARY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1985

FEBRUARY 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

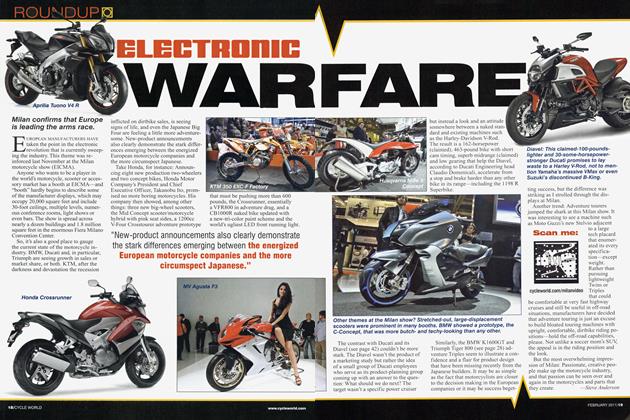

RoundupElectronic War Fare

FEBRUARY 2011 By Steve Anderson