Disliking Change

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

IT'S NATURAL FOR PEOPLE WHO PAR ticipate in an enjoyable activity to regard it in some sense "theirs." Years ago, riders of the AAMRR roadracing organization here in the Northeast held meetings to vote upon various decisions that had been made, which they consid ered unfair or improper. They were tak en aback to discover that AAMRR was a private corporation with shareholders who owned the organization outright.

Something similar happened recently when the AMA’s racing activities were Wd to Daytona Motorsports Group. DMG then made a number of changes in rules and procedures that resulted in the withdrawal of Honda and Kawasaki factory teams from the roadracing series, and may further have led to a steep decline in both participation and attendance. People felt that “You can’t do this to us!” but they didn’t own the sport. DMG did (and does).

The lesson here—if any is needed—is that an activity belongs to those who own it, not to those who enjoy, support or participate in it.

In the 1970s, I knew Harley guys who felt very strongly that the “Harley thing” was theirs. These men spent hundreds of painstaking hours every winter perfecting what they would ride in the spring. Their bikes were not accessories—they were the centers of their lives. How disillusioned they all were when The Motor Company did what it plainly had to do: cashed in on the “CEOs on Harleys” movement that began in the 1980s and continues to this day. For these newbies, Harleys were pretty much the equivalent of the pirate costumes worn at a 5-yearold’s birthday party—a fun, new identity. People joked that they got their do-rags and fingerless gloves from vending machines. The long-serving Harley guys were bitter about this, but clearly the business had shifted its attention away from moving heaven and earth to find rare NOS Knucklehead parts to better serving gold-card buyers who could tack on thousands of dollars’ worth of accessories to an already expensive motorcycle purchase.

We don’t like change, especially when it changes what is dear to us. Motorcycling in general has changed—a lot. In the 1960s, a young person on a Honda S90 felt mobile, free and stylish. A 250, such as Suzuki’s exotic new X6, was a lot of bike. I learned to build engines, lace wheels and read sparkplugs in those years, and went racing in the 1970s—a time when you had to build equipment or do without. Starting from a stock 1972 750 H2 Kawasaki engine, my rider and I built a machine that was actually competitive. How times change! Today you don’t start with an engine, and no one looks at sparkplugs. You start with hundreds of thousands of dollars and hope you have the political skill to parlay your way into some kind of “relationship” with a manufacturer or other large sponsor. Rules tightly limit innovation, because innovation is expensive and, in the new “biz-speak” of event management, it is “de-stabilizing.” What if it’s innovation that interests you? You hang on and hope that one day, the tide will flow the other way again.

Motorcycling was cheap and available in the 1970s—new bikes in every size, dirtbikes, touring bikes, used bikes. Young men in the 16-25 age bracket were large customers because that is the age of energy, of trying to make things happen, of yearning for adventure. But good industrial jobs were becoming fewer and, in the 1980s, those buyers no longer had carefully saved cash in their jeans. The industry turned to those who still had money—the many “bornagain” riders and older men who’d long harbored a secret desire to ride a motorcycle but could not because their lives had been too buttoned-down.

Women have also become significant new buyers. In a very real sense, the newbies so resented by the old Harley men were genuinely seeking freedom, in the form of new experiences. The industry responded by building more-expensive, feature-laden and higher-performing machines for these able new buyers. No more 65cc step-throughs, lOOcc dirtbikes and very few 250s. All that was swept away on a flood of rising sales of bigger bikes. The threshold of motorcycling had risen to be 600cc high.

And so it went—until not so long ago we came to consider 180-horsepower lOOOcc sportbikes normal. The industry wanted to race what it most wanted to sell, so the major racing series adopted a lOOOcc limit. The electronic revolution was on.

Whammo! The economic recession put a lot of us on rice and beans. No more motorbikes. Sales figures dropped so drastically that industry types murmured the numbers out the sides of their mouths. What now?

We don’t know. But I am hearing encouraging noises about American Honda selling every new CBR250R it can get its hands on, and Kawasaki having a similar experience with its little Ninja 25OR, a perennial best-seller. Could attitudes be changing to find a different kind of fun in a smaller-displacement package? With U.S. sales falling, Japanese makers turned to developing nations to seek wider sales, delivering the cheap transportation that has been the default state of motorcycling since the beginning. Sales in those areas are of step-throughs and lightweights.

Now it looks like lOOOcc expectations could be seriously out-of-step with emerging reality.

Will the U.S. market be mended and everything back to normal in three years? Hand me the keys to the Hummer. Then what? Everyone marveled at the original 1998 Yamaha YZF-R1, which stuffed a lOOOcc engine into a package hailed as “barely bigger than a 250.” Will someone do the same with, say, a 1500cc engine?

Or maybe the economy stays at a 250cc size. Japan might react by bringing more of its “third-world” products— suitably equipped—to the U.S. market. Three years ago, the “entry-level” 600cc sportbike cost as much as a small economy car, so when gas prices spiked, motorcycle sales hardly quivered. In a 250-sized market, that would change. Honda’s CBR250R is $4000—a lot less than even a presentable used econobox. That makes buying a motorcycle as transportation attractive again.

As wonderful as they are, lOOOcc electronic sportbikes aren’t everything. They humble their riders and, with top speeds three times most legal limits, they humble their surroundings. Can there be recreational flying in an F-16? There are other ways to enjoy flying besides straight up. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHome At Last

DECEMBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

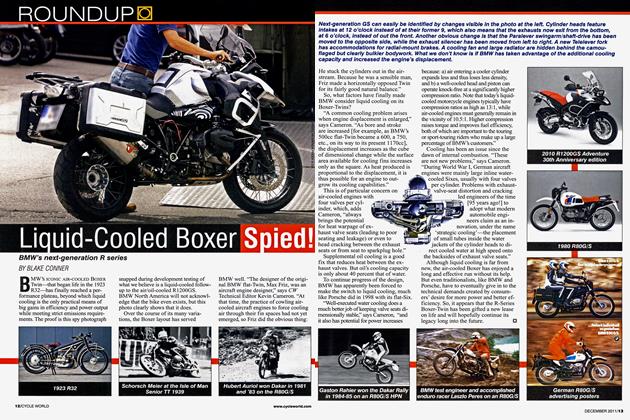

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Boxer Spied!

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

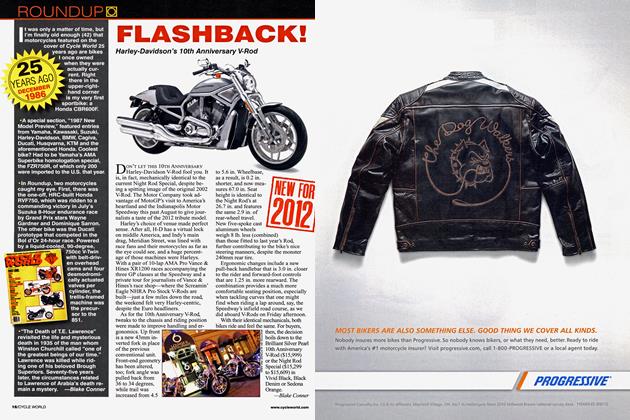

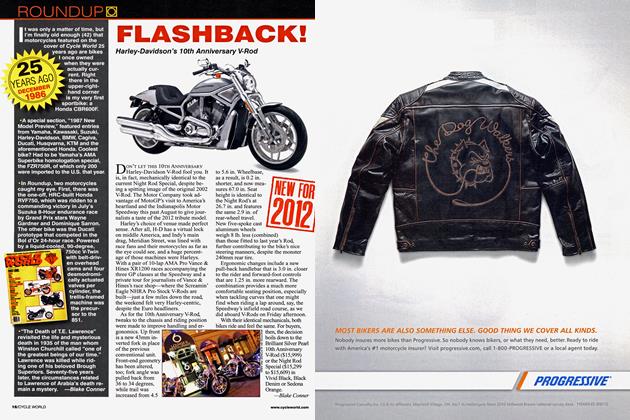

Roundup25 Years Ago December 1986

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupFlash Back!

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

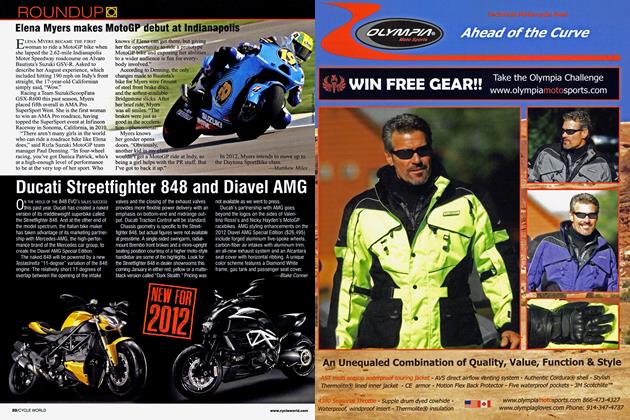

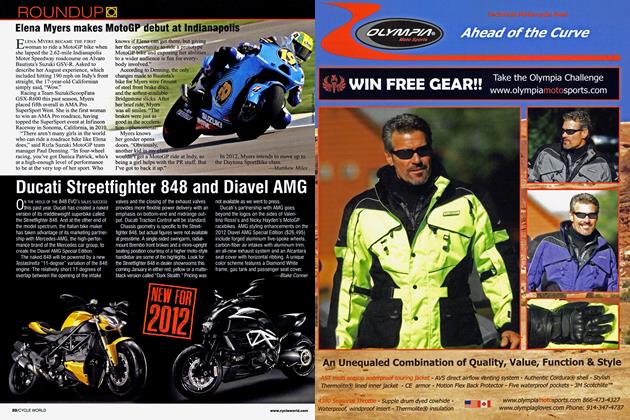

RoundupElena Myers Makes Motogp Debut At Indianapolis

DECEMBER 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupDucati Streetfighter 848 And Diavel Amg

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner