Candid Cameron

I RECENTLY ENJOYED READING FRANKLIN’S INDIANS, A

book by Tim Pickering, Liam Diamond and Harry Havel in, assisted by the late Harry Sucher. The reason for my enjoyment is that this book resolves a question I asked myself some years ago when I learned that the Franklin in question—Charles B. Franklin—had discovered the effect of “squish” upon combustion through his tuning work at England’s Brooklands Speedway.

My question was: Did C.B. Franklin make use of squish in his successful development of the Indian Powerplus racing machines? Persons writing about this era have marveled that the Powerplus—a sidevalve or “flathead” design— could be tuned to compete successfully against overhead-valve machines like the supposedly much-superior Harley-Davidson 8-valve design. Franklin’s Indians shows that Franklin did use squish in accomplishing this feat. At the time, it was hailed as “tuning wizardry,” but it was, in fact, the result of engineering good sense.

Flow through the ports of an overhead-valve engine is much more direct and less impeded than in a flathead.

The flathead’s two valves are located, stem-down, next to the cylinder bore. Intake air must flow up to the intake valve, across to the cylinder, then make a 180-degree turn before exiting downward at the exhaust valve next to the intake. In our world, flatheads are considered suitable only for lawnmowers or the vintage Ford V-Eights much-fancied by the Beach Boys.

At the time in question, the early 1920s, overhead-valve engines had a serious problem: slow combustion. The ignition timings of various ohv motorcycle engines of the period were up in the range of 40 or more degrees BTDC.

The longer combustion takes to reach completion, the longer unburned mixture is held at high and rising temperature, driving forward the chemical reactions that lead to destructive detonation. The result was that ohv engines made good power as long as they were spinning close to the tops of their powerbands. But if they were pulled down to lower revs, they knocked (detonated) badly. If ignition timing were retarded to prevent this, power was lost off the top.

Speed of combustion depends on turbulence, shredding and distributing the flame kernel as it leaves the sparkplug’s gap, rapidly spreading it over a large area. In a 1920’s ohv engine, the only turbulence-generating effect was the velocity of the intake flow, and this process slows at lower engine speeds, allowing knock to develop.

Franklin discovered squish by accident, brazing up a distorted head casting to bring it to the desired compression ratio, then grinding away the braze to leave just enough clearance for the piston not to touch it at TDC. We can imagine that when he first ran an engine so modified, it ran poorly. When searching for a reason, he surely tried adjusting ignition timing. And when he did, he found that this engine needed its timing retarded for best power. When this was done, the engine made more power than expected.

As the piston neared TDC on its compression stroke, the mixture between piston crown and the braze-filled region of the head was violently “squished” out from between, forming a fast-moving jet that stirred the mixture in the main combustion chamber.

Faster combustion gave Franklin what is today called “detonation margin,” which moves the engine farther away from the conditions that favor knock. Race engines are normally tuned to the edge of detonation, so Franklin’s discovery of squish allowed him to safely raise compression ratios. This increased torque even at lower rpm, giving his Powerplus race engines a potential advantage over supposedly more-progressive 8-valve ohv engines. In Indian production engines, this boost to low-end torque gave flatheads their deserved reputation for lowspeed pulling power. Franklin’s Indians includes photos of cylinder heads clearly designed to incorporate squish.

The application of squish to ohv engines did not occur until 1950, when Norton engineer Leo Kuzmicki raised the sides of a Manx Norton’s piston dome until they were uniformly very close to the hemispherical cylinder head at TDC. The resulting jets of mixture accelerated combustion, allowed some ignition retard and compression ratio increase, and boosted power. Every sportbike made today depends upon the same concept for detonation-free high torque from its engine.

Usually, English engineer Harry Ricardo is credited with the invention of squish. Franklin’s Indians shows us that Ricardo was just the first to patent and charge license fees for the concept. Franklin’s discovery came before World War I, years before Ricardo’s, and he carefully kept it for his own use.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

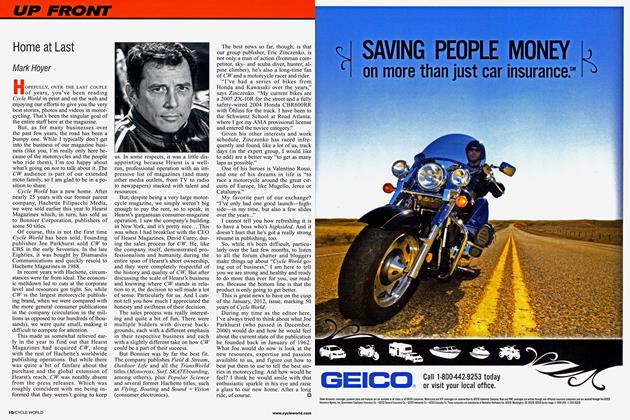

Up FrontHome At Last

DECEMBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

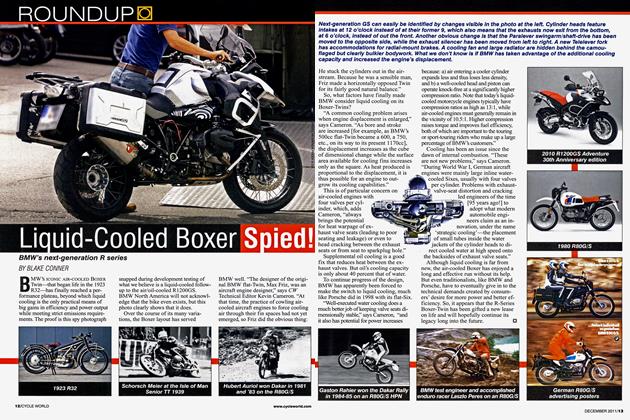

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Boxer Spied!

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago December 1986

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupFlash Back!

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupElena Myers Makes Motogp Debut At Indianapolis

DECEMBER 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupDucati Streetfighter 848 And Diavel Amg

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner