SERVICE

Looking for a buzzkill

PAUL DEAN

Q I am having a bit of a vibration problem with my 2009 Yamaha FJR1300. After about 50-60 miles of highway riding at cruising speeds (6580), my right hand goes numb and both legs up to my knees have a numb sensation. The right-side mirror gets quite blurry at these speeds, too. I bought the bike new and broke it in according to the owner’s manual. I have taken the bike back to my dealer and contacted Yamaha’s main office but have gotten no results or satisfaction. I’ve been riding for almost 40 years, and the FJR 1300 is the first motorcycle I’ve ever ridden that had this problem. Have you heard of any other such complaints with this bike?

Brian N. Fletcher Largo, Florida

A I’ve logged many miles on the various iterations of the FJR since the bike first appeared in the States seven years ago but have never encountered a vibration problem as severe as the one you describe. There’s no doubt that, despite its engine being counterbalanced, the FJR gives off a bit of vibration felt through the usual contact points—handgrips, footpegs, seat—but I’ve never heard of those vibes being strong enough to cause extremities to go numb.

There are a few possible causes of this phenomenon. If the fuel-injection throttle bodies are not properly synchronized, the resultant slight differences in combustion values could result in marginally greater vibration at certain rpm. The vibes also could be a byproduct of engine-mount hardware that is insufficiently torqued. Or, more seriously, it could be that the stack-up of manufacturing variations in your particular engine has resulted in an exceptionally high level of vibration. While the first two possibilities could easily be remedied by a dealer, the third one would need to have the involvement of Yamaha Motor Corporation. If your dealer is no help, you may have to be more persistent in your attempts to contact Yamaha.

There’s even another factor to consider: you. In an extensive study conducted by General Motors during the development of the C5 Corvette in the middle 1990s, the engineers found that the human species has a very wide range of sensitivity to vibration. While certain vibration frequencies have virtually no impact on some people, other people are significantly affected by them. The study determined that age, weight, bone structure, even gender can play a role in the way in which any given individual might react to certain vibration frequencies and amplitudes. Chances are that this is not a factor in your situation, but it’s still something to consider, given that the FJR 1300 is not known for having such an adverse effect on its riders.

One way to be more certain is to somehow arrange a ride on another FJR1300, preferably a 2009 model. If the same numbness occurs when you ride that bike, it would seem that you and the F JR are not a good match.

The dogs of wear

Q I recently bought a 2006 Suzuki SV1000S that just turned 11,000 miles. It runs great except for one problem. When I shift into second, it sometimes jumps right back out into neutral, especially if I shift quickly, and if I accelerate hard in second, the transmission skips, almost like some teeth are missing. When I ride more conservatively and shift normally, there is no problem and the transmission works perfectly. Is there an adjustment in the shifting linkage that could fix this problem or is it going to require something more extensive? I hope it’s nothing too serious because I spent most of my extra cash to buy the bike.

Tom McAllister Lakeland, Florida

A I don't have good news, Tom. In all probability, the secondgear shift fork is bent and gouged, and the engagement dogs for second have likely been rounded off. Repairs will involve removing the engine and splitting the cases to gain access to the transmission gear cluster. The cases on the SV's V-Twin engine are split vertically rather than horizontally as on inline-Four engines, so the job requires removal of the heads and cylinders-a complete teardown, in other words.

This kind of transmission damage generally is the result of repeated harsh and/or poorly executed shifts. When a transmission is shifted, the faces of the engagement dogs for the affected gears initially bang into and bounce off of one another for a tiny split-second as the dogs fully engage. This is especially so during a first-to-second shift, where the difference in the speed of the two mating gears is greater than it is during any other shift. Why? Because in virtually all transmissions, the ratio gap between first and second is greater than it is between any of the other gears. If the shift is made cleanly, which is the case when done properly, that initial impact is small enough that it does no damage to the dogs or shift fork; but if the shift is botched or brutal (poorly timed power-shifts; clutchless shifting without matching road speeds to engine rpm; shifting too slowly, etc.), the gear dogs can initially slam off of one another in a manner forceful enough to begin rounding off the edges of the dogs, bending the shift fork and gouging the base of the fork in a way that eventually causes the fork to fit too loosely in its groove on the gear.

In your SV1000S, all of those condi tions are likely to be present. The bent! gouged fork is not allowing full dog engagement, and the dogs are rounded off; so when you try to shift quickly, the rounded edges of the dogs reject one another, kicking the tranny into a false neutral. And when you accelerate hard in second, the combination of rounded dogs and lack of full engagement causes the dogs to jump over one another, resulting in the “skipping” you describe. The only solution, I’m sorry to say, is replacement of all the damaged transmission components.

FeedbackLoop

Q In the "Gone with the wind" letter in the January issue, Terry Arnofti described a problem with his Suzuki GS500 sputtering and running poorly in exceptionally windy condi tions. I've had this same problem with two of my bikes. The first was a 1982 Suzuki GS85OGLZ, the second was a 1984 Honda CB700SC Nighthawk S. I resolved the problem on both bikes by rerouting the carburetor float bowl vent tubes to keep them out of the wind.

Bruce Rettig Carlos, Minnesota

A Thank you, Bruce. Your input was short, to the point and informative. I’m sure that Mr. Arnold appreciates the feedback even more than I do.

What’s in a name?

Ql’ve had a subscription since I turned 18 and got my first bike. I’m a big fan of the old Honda CB series, having owned three previously and three more currently. I’m very proficient in solving bike problems, but this one’s a stumper: Why are they called the CB series? I mean, Kawi gets cool stuff like ZX and Suzuki gets GSX-R, but my beloved Hondas are the lame CB. Citizens Band? Maybe Mr. Honda had a thing for the trucker scene. Please enlighten me as to what CB means.

Greg Senger Clarion, Iowa

A Honda's model nomencla ture goes back almost to the company's very beginnings. In the early 1950s, Soichiro Honda built and sold 50cc two-stroke engines that could quickly be attached to bicycles, thus offering exceptionally cheap

motorized transportation to a country still recovering from the devastating effects of World War II. He called that engine the “Cub,” a name that would be applied to the company’s first 50cc step-through a few years later. That ubiquitous model had a couple of slightly different iterations that needed to be identified more specifically than just calling them all Cub, so they were given separate letter-and-number designations; and, the story goes, since the first letter of Cub is a “C,” those bikes were simply called Cl00, CA100, Cl02 and so on. C then became the first-letter designation for most Honda streetbikes, including the original CB72/77 Hawk/ Super Hawk, the CL72/77 250/305 Scrambler, the CB/CL350, the CB750 Four, the CX500/650 transverse V-Twins and even today with the CBR1000RR and CBR600RR. There have been exceptions—such as the S90 and S65 Singles of the 1960s, the SL “Motosport” series, the VFR V-Fours, the GL Gold Wing flat-Sixes, the VT/VTX V-Twin cruisers, etc.—as well as a few other inconsistencies in the naming protocol. But otherwise, “CB” has remained the first two call letters for the company’s inline-Four and vertical-Twin street models.

Numerous motorcycles over the past half-century have had “Z,” “Y” and “X” in their names (the Suzuki X-6 and Yamaha YDS3 of the 1960s, for example; the Kawasaki Z-l and Yamaha XS series of the ’70s), so it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when the “cool” model designations you refer to came into vogue. Kawasaki may have gotten the ball rolling with its GPz series of the early 1980s, but with the landmark GSX-R750 in 1985, Suzuki shifted the trend into high gear. Lots of X-Y-Z model names soon became prominent— Kawasaki with ZX, ZRX and ZX-R, Yamaha with YZF600R, YZF-R1/R6 and FZ1/FZ6, and Suzuki even adding GSX (minus the -R) nomenclature to a few non-repli-racer models.

Whether or not any of these names are cooler than others is purely a matter of opinion. Besides, the motorcycle is what provides the real joy, not its name.

Got a mechanical or technical problem and can’t find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach,

CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631 -0651; 3) e-mail it to CWIDean @aol.com\ or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10-page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do provide enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. Include your name if you submit the question electronically. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreat Leaps

JUNE 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

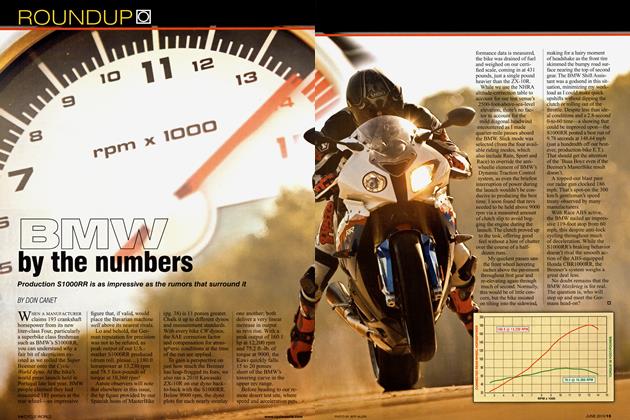

Roundup

RoundupBmw By the Numbers

JUNE 2010 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupTeam Cycle World Is Going Racing!

JUNE 2010 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupThe Way It Was

JUNE 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago June 1985

JUNE 2010 By Matthew Milles -

Roundup

RoundupKtm Goes Electric!

JUNE 2010 By Blake Conner