RUNNING of the BULLS

Welcome, amigos y enemigos, to the 11th running of the horniest racetrack superbike shootout in Spain

MARK CERNICKY

MASTER SUPER BIKE 2010

LIKE THE BIG PLANS THEY STARTED WITH WHEN IT CAME TO CARVING THE BRAND-SPANKINGnew Motorland Aragón into the high-desert backcountry of Spain, I had big plans for MasterBike 11, back on schedule after a year off due to financial constraints and in streamlined form. Rather than being made of three classes—divided among middleweights, the odd 750, Twins and Open-classers—as in the past 10 MasterBike events, this year we’d keep it simple, raging on the new crop of liter-class bulls exclusively. And instead of three days of timed testing like before, we’d get a single day of practice to learn the new circuit and familiarize ourselves with the nine superbike contestants, followed by four flying laps on Day Two—sort of an extended Superpole—to find the winner.

Just me (the lone North American) and 14 other, ahem, “journalists” from around the world—some of whom, just between you and me, have never ridden a word processor in anger.

Any masterpiece starts with the first line or mark, like learning a racetrack starts by drawing your first entry line, picking a reference mark for the first comer. Allow me to start drawing you a picture: Track temperature on Day One was just above freezing and rainy weather (that ultimately shortened our testing day and kept me from practicing on three of the nine bikes) was on the horizon, which made for cautious first laps. Under these conditions, the logical choice for me to begin practice on was the Honda CBR1000RR, reigning MasterBike from the last round (at Circuito Albacete, Spain— CW, September, 2008) and also my beloved long-termer, meaning I was well familiar with the bike. It didn’t take much more than a lap for the fim to begin. Okay, I’ll be honest: I’d already done 20 laps or so a couple days prior thanks to Kenny Noyes’ gracious invite to let me ride the Moto2 bike he’ll be campaigning this year—a Jack & Jones, Antonio Banderas Racing, Harris-framed machine (for a riding impression with video, visit www.cycleworld.com/moto2).

When the tires met the tarmac, they found only a few small braking ripples (caused by Formula One and GTP car testing) but not a seam or a single chassis-upsetting bump. The cold and smoothness made slides no problem, and by the end of lap one ripping up the fourth-gear front straight, I backed the CBR into the square left-hand second-gear Turn 1, just for fim (and photographic effect) to begin my second lap.

All systems go! Wheeee\ I may have taken it a bit too far in Turn 4, though. It’s a fast, fourth-gear left kink, and when I flicked the CBR in, the bike stepped out so violently it slapped off the steering stops! Honda’s Electronic Steering Damper straightened us out, but with an off-track trajectory at 120plus mph. After a little bunny-hop over the curb and clearing a 3-foot-wide strip of wet Astroturf, I got it slowed and back under control on the pavement run-off that surrounds most of Motorland. It was nice not to go careening off a tire wall. Forget the FIM, this track just got the MC first-hand safety YES! of approval. Unbelievably, I had a second big slide a few comers later at the finish of my lap, which was a clear indication that the OE Pirelli street tires were also finished.

Speaking of tires, this edition of MasterBike was also the first time each manufacturer was allowed to pick its favorite-flavor Os instead of using a control tire chosen by the organizers; a mixture of Dunlop, Metzeier and Pirelli was cause for extra attention. Add this to all the other elements a rider needs to take into account during a test like this: lever adjustments, clutch engagement, brake feel and chassis feedback, not to mention the power variability of the different engine types—V-Twin, V-Four, inline-Fours—of these nine different machines.

Times were monitored during practice day so that during timed laps the following day, faster riders would take off first and no one would be caught from behind. After successful practice, on Day Two I lined up second behind former Italian Twins Champion Franco Zenatello and ahead of reigning Scandinavian Superbike Champion Freddy Papunen (can you say “ringer”?). Pressure?! What pressure? Just relax and ride. It was essential to find a rhythm of calculated risk for four timed laps: Crashing was simply not acceptable, and I reminded myself to maintain a 10 percent safety margin at all corner entries—easier when I decided not to compare my lap times to anyone else’s until all was said and done and all nine bikes were run.

On “race day,” luck of the draw put me once again on the Honda CBR1000RR as my first bike. Rolling down pit lane,

I was calmed with faith the size of a mustard seed, a pair of fresh Pirelli Supercorsa SC2s and, truth be told, how much fun MasterBike really is. The Honda team had implemented our setup suggestions, and the CBR was working great. There was lots of controllable power whenever I needed it thanks to that strong engine and just-right gearing; because there was no lag when snapping open the throttle and no running into the rev limiter, I could finish corners on the gas and steer with the rear. Comer entry was equally good: Aiming for the right of the chicane, I could tmst in weight transfer to give me good front-end feel before turning into the apex.

Alas, after only a few laps, spongy-lever brake fade cut into the fantastic feel and that fine line of control it had provided. Still, the CBR1000RR was stable at speed and pivoted around corners with resounding, tail-happy ease. But while the CBR’s chassis setup was positively intuitive and sliding is fun, sideways isn’t forward. Best lap: 2:04.013. Still, the Honda is the lightest of the Fours and that helps rideability a lot. Kei “Nasty” Nashimoto’s observations were spot-on: “The Honda CBR1000RR feels small, not too much effort to move around. Its engine makes very usable, broad power, and the suspension was the best for me.” Hai!

Next up, and polar opposite of the CBR: the KTM RC8R. It’s longer and less lively, and the torquey Twin’s even power pulses—delivered through the great grip of its Dunlop D211 Supersport race tires—allowed me to lean hard into learning Aragon’s nuances during practice. And it didn’t hurt when ex-GP rider Jeremy McWilliams came past on the other RC8R he was there to set up for KTM. I tucked in for a tow on five warm-up laps nowhere near as exciting as my CBR ride but probably quite a bit faster.

Rolling down pit lane, I was calmed with faith the size of a mustard seed, a pair of fresh Pirelli Supercorsa SC2s and, truth be told, how much fun MasterBike really is.”

MOTORLAND AIU~GON

Total Length: 3.3 miles

Width: 40-50 feet

Length StartlFinish Straight: 4/~~ mile

Maximum Rise: 5.4%

Maximum Fall: 7.2%

Maximum Elevation Change (17 to 116): 164 feet

Designer: Hermann hike

NEWSFLASH!! This just in: Motorland Aragón will host the 14th GP of 2010 on September 19, replacing the Hungarian round.

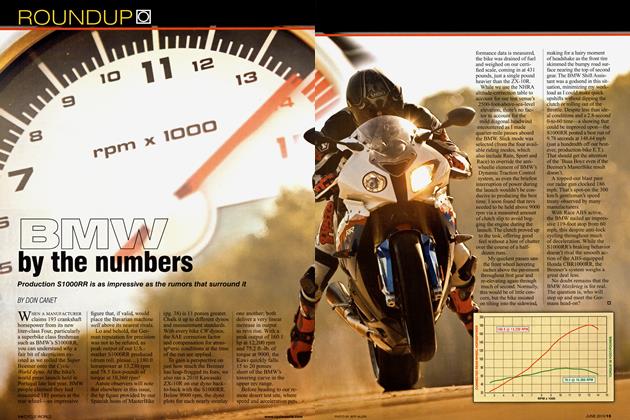

*MASTERBIKE GPS TIMES PROVIDED BY MASTERBIKE MAGAZINE OF ITALY RIDER FRANCO ZENATELLO (2ND-FASTEST OF THE FAST SIX)

For timed laps, the RC8R was such a piece of confidence inspiring engineering that I could have ridden it all day and not gotten tired. Finely set up WP suspension combined with linear power delivery to never upset the chassis anywhere on the track. This bike steers quickly enough to finish sharp corners without ever feeling like you're going to run wide, yet • ••••. remains stable while running wide-open in fifth geai~ Great grip and linear torque produce the kind of predictable, smooth acceleration that builds confidence, while the Brembo brakes are an outstanding insurance policy when it comes to late, hard braking; like Motel 6, they leave the light on for you.

Riding the RC8R, I could just think about the track and trying to get the most out of the Spanish real-estate. In hindsight, I think I got in the way of the Twin's torque in a couple of corners: I Jeaned over too far at the apex and didn't use the entire track exiting a couple of important fast corners (where on the Honda I would have to leave a foot for the hinged-out powerslide). The RC8R's wheels were always lined up and locomotive driving. Like I said, I think I could have done 2:03.834s all day long. They wouldn't let me. There were more bikes to ride!

There was no official factory test rider on hand to help dial in the Suzuki GSX-R1000, so Motociclismo MasterBike’s Master of Ceremonies Victor Gancedo asked me to help with chassis setup. I rolled out to get a feel for the bike and three laps later came in and requested a lot more rear-spring preload and some additional rebound. The support techs just smiled and said, “You can ride a couple more laps, okay?” Uh, okay... So there I was, exiting Turn 16 spinning and sliding almost like with the Honda but getting a lot less traction feel. I also ended up unintentionally rushing a lot of corner entries because I couldn’t get the GSX-R to downshift unless I deliberately pulled the clutch lever all the way to the grip. That heavy-steering drama made me break my first sweat of practice day, even though the ambient temp was still in the 40s. Time for a rest and a Red Bull recharge.

Come timing day, nothing much had changed. Yeah, the Suzuki was fast, and soft rear suspension kept the GSX-R super-stable on the straights, but I still couldn’t get it to turn. Three turns of rear-spring preload would have helped the Suzuki turn like a world-class sportbike rather than like a VW bus; as it was, I did my best to square up corners to get the thing turned and off the deck. Reading rear grip was also made tough by the squishy suspension—which further caused the front to push in the important fourth-gear lefthand Turn 11. The necessary full-clutch-pull downshifts made concentration-consuming corner entries laborious, and made me more passenger than Master of this vessel. Properly set up suspension is a big reason bikes win races and MasterBike. This unsorted Suzuki suffered under me and my lap time reflected it: 2:04.509. Then again, Motociclismo Spain’s Oscar Peña set his second-best time (2:04.488) on the Suzuki, saying he felt very comfortable on the GSX-R and that its power was easy to use. Could it be because he races a SuperStock Suzuki 1000? Certainly can’t hurt, but Óscar also has a much more “Euro” style of riding than I do, meaning he tends to carry a more arcing, flowing line than my get-itin, get-it-turned and drive-it-out method.

The Kawasaki ZX-10R felt almost as familiar as the CBR, so with a quick adjusting of levers, off I went. A lap later I started giving the green goblin a good go and quickly remembered how fast the 1 OR is, but at the same time I missed the old ’05 model’s meatier midrange; this bike felt “in between gears” in a couple spots and didn’t seem to provide the same torque to pull it through. Pushing harder, I never found the nervousness I associate with the previous ZX-10R; on the contrary, the lazy-steering, top-heavy 10R was hard to pull down to the apex of tighter corners and required a fight to finish the exits.

Next step was to try some deeper trail braking and use more engine braking by running a lower gear going in than I really wanted to use for the exit. This took a lot of grunting effort and some extra eye-of-the-needle clutch work, and with that drawing my attention, I missed an upshift one lap; luckily, I didn’t get rear-ended by the three riders who were tucked in behind me.

On race day, the Kawasaki’s setup was still somewhat top-heavy-feeling and slow-steering to help stabilize things down that long back straight. Braking wasn’t as impressive as that provided by the bikes with Brembos; if the 10R were my bike, I would experiment with pad compounds. I’d also like to change gearing to make better use of second and raise the engine rpm out of a torque lull that surely added more than a tick to the lOR’s times. Still, my four laps were a good reminder of how fast the Kawi is. No transmission issues, and shifting my weight a bit more took full advantage of the green machine’s speed by getting it mostly turned before picking it up off the deck and opening the throttle—fire in el hoyo! My 2:03.848 time surprised me by edging out my best on the Honda, which felt much easier to ride.

The turbulent, visceral engine vibes of the BMW S1000RR really reminded me of my old, built-to-the-hilt 2001 Yamaha YZF-R1 AMA Formula Xtreme racebike but with even more massive urge. The BMW’s raw power was amazing, and with traction control set to Slick mode, wheelspin was tempered only by what was left of the Race 1 Metzeler rubber’s usable life. Rest in peace, my friend...

During the first laps, I spent a lot of time power-sliding during exits by late-apexing. After I found so much confidence in exits, the BMW began to convince me to put a little faith in front-end grip, too. More corner speed meant more lean angle and made my size nines start dragging, so I pulled in to save some boot to kick ass tomorrow.

When tomorrow came, the scuttlebuzz was that the BMW had posted some impressive practice times. I steered clear of Motociclismo's Guillermo Artola at MasterBike timing and scoring, concentrating instead on my four laps and my 10 percent safety margin as I started charging ahead on track.

Was it just me, or was the quick-shifter’s kill duration too long as I made the short shift for the important Turn 10/Turn 11 left-hand combo where you spend what feels like 10 minutes a lap on the side of the sliding tire? Something wasn’t right; I could feel the traction-control system cutting in instead of letting me cut loose.

Unfamiliar with the BMW, I pressed on and continued to feel the shame and frustration of acceleratus interruptus at every corner exit. Along the downhill back straight, the S1000RR was a missile. But when I went for the brake and two backshifts, the bike wouldn’t let me; I had to take to the run-off. Flustered and at a loss, I turned around and went after what was left of my allotted time. Downshifting worked without a glitch when I did it at lower rpm and used more clutch (like with the GSX-R), and at least I could get the BMW turned with less effort than I could on the Suzuki.

..shifting my weight e hit mi ire took full advantage of the green machine’s speed by getting it mostly turned before picking it up off the deck.

But I continued to feel the bike’s traction control busily working away at every turn, and my boots kept dragging, keeping this bike from being my favorite. Yet the two other fastest Masters mustered their best times on the S1000RR. What gives?! Upon my return to the pits, the BMW support staff wanted to know what went wrong. I confessed my electro-inhibitions, and they went straight to the right handlebar. “Ah!

You just rode it in Sport mode! It should be in Slick setting!”

What’s that mean? In Sport mode, the BMW system provides liberal intrusive interruption of power when accelerating while leaned over, puts the kibosh on steering with rear wheelspin, delivers a Newport-BeachPD level of wheelie inhibition and allows ABS to shut my hacked-out corner entries right down. The BMW people tell me Slick mode would’ve taken at least a second off my best time of 2:03.662, and that would’ve made it my fastest time.. .but no.

Even in Slick mode, Freddy Papunen from Motorrad Sweden, who set the fastest time of the whole test on the BMW—1:59.927—felt like the bike held him back just a bit: “When I pushed for lap times, the traction control cut in a little too aggressively while changing direction under acceleration. It also stopped some small wheelies and I didn’t like that.” But you can’t argue with the raw numbers. This thing is fast.

On practice day, drawing lines on Motorland’s flowing pavement with the Magic Marker Aprilia RSV4 Factory

made it easy to connect the dots and not color over the lines. A balanced chassis and well-set-up Öhlins suspension made late braking and squaring up tighter turns a labor of love. Lean as deep as you like; there are zero issues with cornering clearance, unlike with some of the other front-runners. Acceleration on the RSV4 starts low, with the torque of a Twin, and as the revs rise, its engine pulses smooth out as it pulls hard toward an inline-Four-like finale. Every rider I had a chance to talk with echoed my high opinion of the Aprilia, including Papunen: “A great chassis and awesome engine make it feel like a MotoGP bike. Sharp handling and very fun to ride!”

Race day only confirmed my Aprilia infatuation: When I play those four flying laps back in my head, the only bad I can remember is being chucked out of the seat exiting Turn 7 whilst looking for the edge of the track and some traction at the same time. I found both simultaneously, thank God, and landed back on the Aprilia rather than directly on the perfect pavement in my nice new leathers. Instead of thinking about what might be wrong with the Aprilia, all I recall is: “This is faster than I’ve ever gone around here before.” Balanced Öhlins suspension, Brembo brakes and Pirelli grip allowed me to clear my mind of worry and attack the track for a best time of: 2:03.422. Not bad.

Too bad rainy weather ended our practice day early and kept me from testing the Ducati, MV Agusta and Yamaha. Thankfully, because of all the laps I’d already run, I was very familiar with the track. Plus, I’ve got lots of seat time on those machines.

I had to start off my timed laps cold on the Ducati 1198S Corse. Why? I wanted to make sure the other MasterBikers had nailed the setup.

The 1198S Corse offers lower bars and a more aggressive riding position than the other Twin—the KTM. This meant I was leaning off and sighting down the side of the special-edition Due’s graphics at the Pirelli front tire, DTC set to level 3 and working seamlessly. What incredible engineering art elevates the riding experience! Such a beautiful thing... But there were a couple of problems: When I transitioned the 1198S side to side in the backward baby Corkscrew—Turn 8 and Turn 9—there wasn’t enough rebound damping and the rear felt like it was hopping off the ground, adding precious tenths to its lap time. Also, trying to get out of the wind on the back straight required my face to be down on the special factory-racer-style aluminum tank and a white-eyeball inspection of the steering damper while I watched for the red haze of the shift light on the inner curve of my faceshield.

On the other end of the straight, though, solid braking, a stable chassis and that booming engine on overrun (with a nice slipper clutch) made for audio-enhanced racetrack enjoyment. Sadly, footpeg position interfered with the Ducati’s massive attainable lean angle and I ruined my boots—but I still enjoyed every tick of the 2:04.819 best lap.

During my four frantic fast laps on the MV Agusta F4, only the best and worst highlights of what made me fast or slow stand out. Rolling onto the track, I already felt a bit more over-the-front of the new F4 than on the previous 312 F4 I’d ridden a couple of years ago. I was a little distracted by the Agusta’s beauty from the saddle until my rapidly escalating speed brought things back into focus. Sliding out to where the traction control (set on level 3 of 10) began to kick in made me think this MV must go to the same tailor as the Ducati; the system worked seamlessly as I felt it tempering traction of the Pirelli Supercorsa rear tire and keeping the F4 sliding along at an attack angle of about 10 degrees. This was an incredibly cool sensation, with that soft buffer of electro-magic keeping evil at bay. Tucked in,

I had time to admire the levers and master cylinders before fanning the clutch on the F4—instead of shifting—between the right/left chicane leading to the back straight... I was in a hurry but I didn’t worry: Monobloc Brembo brakes were there to take the heat for me.

This charge was over too soon but was good while it lasted at 2:04.329. I’ll have to agree with a Frenchman on this one. Said Moto Journal s Mathieu Cayrol, “The MV has agility and stability, turns easily and is still stable at speed, even during hard braking.” An incredible machine and in the top three of the final results.

Thirty-two laps down, four to go. The final bull for me to take by the horns was the Yamaha YZF-R1, another bike I didn’t get to practice on. Still, because the R1 has excellent ergos, it’s just the kind of rider receptor I’d need for my final assault on “Motodragon” Aragon. Another plus is the Yamaha’s easily discernible power delivery and excellent suspension compliance, the latter helping the bike rock like a metronome though the chicanes. That cadence carried through my session on the R1—which seemed to go perfectly, not a wheel out of line, every reference mark hit, on the gas early exiting comers. Sadly, it only seemed easy because we were going so slow: 2:05.941 is a couple seconds off the pace of the fastest bikes. Could it be down to the fact the Yamaha support crew chose the Standard map setting to save on tire wear? Last year in Oschersleben at the big liter-bike track test (CW, August, 2009), the R1 was faster that way. Oh, well, at MasterBike you only get one shot. And a year to think about the next one.

It’s a cruel world. There can only be one winner.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreat Leaps

JUNE 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

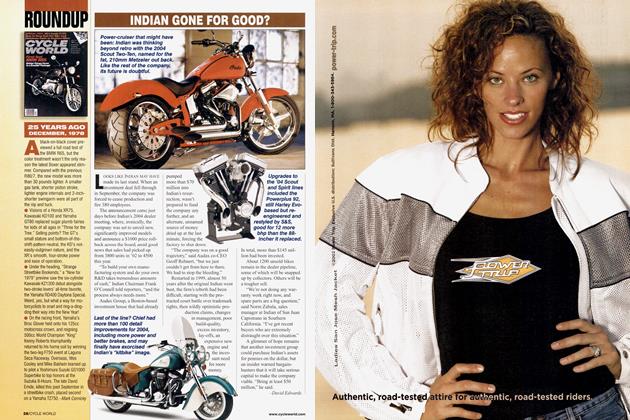

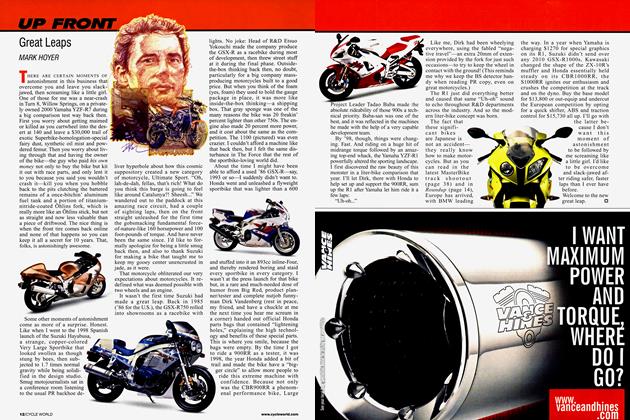

Roundup

RoundupBmw By the Numbers

JUNE 2010 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupTeam Cycle World Is Going Racing!

JUNE 2010 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupThe Way It Was

JUNE 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago June 1985

JUNE 2010 By Matthew Milles -

Roundup

RoundupKtm Goes Electric!

JUNE 2010 By Blake Conner