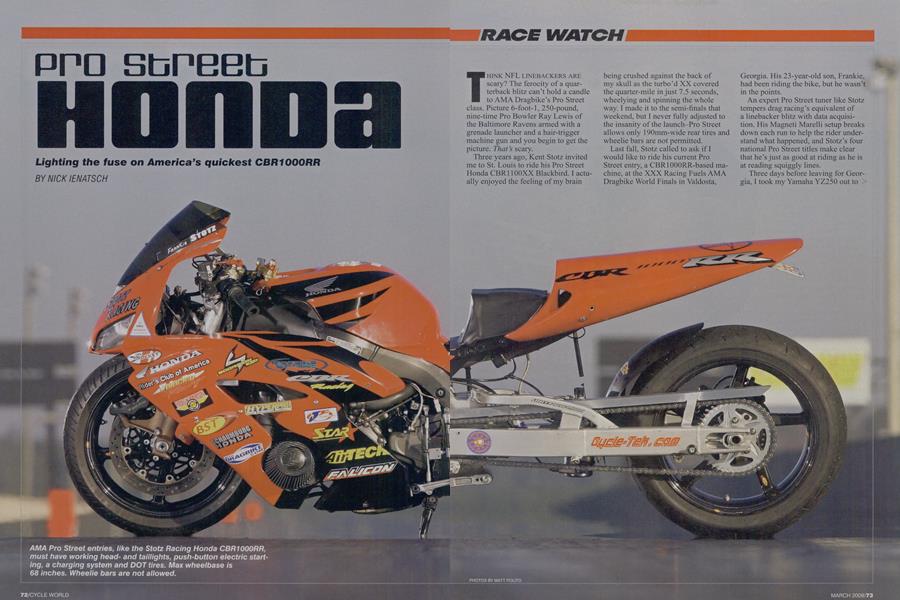

pro street HONDA

Lighting the fuse on America’s quickest CBR1000RR

NICK IENATSCH

RACE WATCH

THINK NFL LINEBACKERS ARE scary? The ferocity of a quarterback blitz can’t hold a candle to AMA Dragbike’s Pro Street class. Picture 6-foot-1, 250-pound, nine-time Pro Bowler Ray Lewis of the Baltimore Ravens armed with a grenade launcher and a hair-trigger machine gun and you begin to get the picture. That’s scary.

Three years ago, Kent Stotz invited me to St. Louis to ride his Pro Street Honda CBR1100XX Blackbird. 1 actually enjoyed the feeling of my brain

being crushed against the back of my skull as the turbo’d XX covered the quarter-mile in just 7.5 seconds, wheelying and spinning the whole way. I made it to the semi-finals that weekend, but I never fully adjusted to the insanity of the launch-Pro Street allows only 190mm-wide rear tires and wheelie bars are not permitted.

Last fall, Stotz called to ask if I would like to ride his current Pro Street entry, a CBRIOOORR-based machine, at the XXX Racing Fuels AMA Dragbike World Finals in Valdosta,

Georgia. His 23-year-old son, Frankie, had been riding the bike, but he wasn’t in the points.

An expert Pro Street tuner like Stotz tempers drag racing’s equivalent of a linebacker blitz with data acquisition. His Magneti Marelli setup breaks down each run to help the rider understand what happened, and Stotz’s four national Pro Street titles make clear that he’s just as good at riding as he is at reading squiggly lines.

Three days before leaving for Georgia, I took my Yamaha YZ250 out to > practice “throwing the clutch.” I practiced in soft loam, bringing engine revs up as I leaned forward over the handlebars, eyes on an imaginary “Christmas Tree.” Time and again in St. Louis, I had “hung” the clutch; quickly releasing the lever on a 500-horsepower motorcycle without the safety of a wheelie bar is scary to the point of soiled pants.

I did two more things to prepare for the world finals. Because Pro Street doesn’t hold 1000s racing against larger-displacement Suzuki Hayabusas and the like to a minimum weight, I ate sparingly to be as trim as possible: “Just water and a carrot for me, please.”

Second thing I did during the month before the race was to practice “cutting a light” with quick, well-timed movements of my left hand. If a bird was sitting on a nearby fence, for example, I’d try to throw the clutch as it twitched prior to take off. I found myself throwing the clutch whenever someone twisted a doorknob, reached for a fork or opened a car door. So there I was, dieting and twitching, hoping I wouldn’t waste Stotz’s time.

Stotz picked me up at the Valdosta airport on Thursday night and brought me up to speed on the way > to South Georgia Motorsports Park.

Crew chief Mark Harrell met us as we rolled into the parking lot, and I spent the next hour riding the stretched RR slowly around the pits and practicing the launch sequence.

“You want the shift light to be just flickering when you stage,” Harrell told me.

Not too tough in a dark, quiet paddock, but the next morning there was nothing dark or quiet about the world finals. The well-prepared South Georgia facility was packed, every inch of paddock space filled with some of the best drag racers in the country, including teams from Canada, Central America and Europe. Stotz’s lone Pro Street Honda garnered plenty of attention, but only two people in the pits-Stotz and me-thought we could do well. And I wasn’t completely convinced...

My re-introduction to Pro Street came mid-morning, and it only took 7.814 seconds to re-addict me to this class. Four passes later, I had improved to 7.396 at 195.19 mph, with a best reaction time of .028 (three years ago, my best was .122). Saturday would bring three rounds of qualifying; eliminations would begin Sunday with the 16 quickest Pro Street machines. As the sun set on Friday, the quick guys were already in the 7.20s, but I had Kent and Frankie> in my ear, feeding me advice. Kawasaki rider Rickey Gadson gave me a hug and asked how my “seven-thirty” felt. Good, Rickey, but not quick enough.

Pause here for a summary of my mistakes, as highlighted by the data acquisition and encyclopedic Stotz. My spin-out

from the burnout box was too long, and I was crooked at the line. When I launched, I got out of the groove and spun the tire.

I left my fingers curled around the clutch lever, that small amount of pressure not allowing the boost control switch to engage. I shifted too early, then too late,

engine revs banging the limiter. On one pass, I never even got to full throttle! I left the line with too few rpm, then too many and damn near flipped over. I staged too quickly. I staged too slowly.

I hung the clutch. I increased throttle too early, “driving” through the clutch and not just ruining the mn but toasting the clutch, necessitating removal and cleaning of the oil filter, pan and pickup screen. Why so many mistakes?

Fear, pure and simple.

On Friday, I learned two things: If the pass isn’t nearly perfect, you leam next to nothing; it’s just a waste of time and money. Seven-sixties, for example, are worthless. Second, Stotz’s CBR needs the rider to do certain things at certain times.

“When Frankie started riding my Pro Street RR, he was doing a few things differently than I did, and I tried to tune the bike to his technique,” said Stotz. “Didn’t work. We had to go back to basics and re-educate Frankie on certain techniques that work on a bike capable of running Twenties.”

Saturday offered three chances to qualify. I ran 7.32 and 7.39 on my second and third runs, with a best speed of 192.5 mph. The former put me in the fast half of the field, fourth quickest behind the Suzukis of Velocity Racing’s Mike Slowe (three-time Pro Street champ), Barry Henson (two-time > number-one plate-holder) and Sebastian Domingo of Nxt Level Racing.

Suddenly, I found myself smack in the middle of the Pro Street title fight: Slowe versus Nxt Level’s Walter Sprout, who had qualified 11th with a 7.483. Velocity and Nxt Level are the two top Pro Street turbo makers, and each squad wanted the number-one plate. If I survived the first two rounds,

I was almost guaranteed to meet Slowe (7.210) in the semi-finals.

There was additional drama. When Harrell tried to fire up my bike on Saturday night, the data system wasn’t working. I asked Stotz what it handles. “Everything,” he replied. “Our internal battery is dead, and the unit needs to be returned to Italy. We need another ECU.”

Salvation came via one of our competitors, not uncommon in drag racing. Dunigan Racing’s Dave Dunigan stripped his team’s turbocharged drag-racing snowmobile (really) and pulled its ECU. That gracious move would come back to haunt Dunigan on Sunday.

My fear of a first-round elimination evaporated when Jeremy Rossi’s bike popped in qualifying. Thank God my first run was solo, because I overcom-

pensated for one of my earlier mistakes, lined up pointed too far left, almost took out the center cones and slithered and spun to a 7.690, the fourth-slowest

run of the round. Meanwhile, Trevor Altman, Slowe and Domingo all ran in the 7.20s. Gulp.

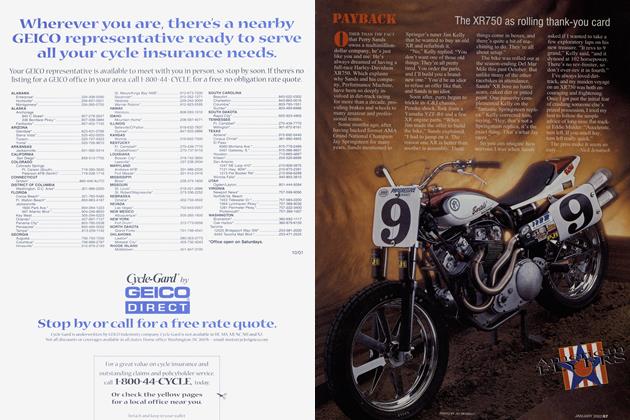

I did a better job in the second round, beating Dunigan Racing’s Bud Yoder’s 7.56 with a 7.34 and an .023 reaction time. Yoder’s engine failed mid-run. Thanks for the ECU, buddy! I should have been happy to make the final four, but both Slowe and Domingo made record passes. Moments after Slowe ran 7.183, Domingo stormed by with a 7.181, stealing the 10 valuable points awarded to a record-setter.

Ten minutes before the semis, Slowe and I found ourselves together at the staging lights, looking over the track. Stotz runs a Velocity turbo, but Slowe made it clear that he would rather beat me than have a free pass to the finals. “HI be more upset if you lay down than if you beat me,” he said.

Well, I beat him.

He ran a 7.205 to my 7.280, but my reaction time of .003 made the difference. He cut a . 113 light but couldn't overcome my lead. I’ve long admired Slowe’s riding, and my respect for him grew when he congratulated me in the cool-off area.

“I'd sure appreciate it if you beat Sprout,” he said, acknowledging that I’d just taken a big bite out of his championship hopes, even if his earlier 7.183 pass also set an eighth-mile record of 4.75, earning the likable Pennsylvanian 10 more points.

The second semi came down to team orders. Sprout launched and Domingo waited a half-second before pulling the trigger on his intercooled Hayabusa. Domingo ran 7.243 against Sprout’s 7.411. but the head start put Sprout in the finals against me. With the top three qualifiers-Slowe, Domingo and Henson-out, Stotz's lone Honda w ould take on Sprout’s Suzuki.

Then we heard the news: Sprout’s bike blew up during his free pass to the finals, and the team had to change engines. That might have been okay earlier in the day, but with the finals approaching and fewer bikes in contention. things were moving quickly.

I was euphoric. I’d timed my best light and made my best run against the nation’s top rider. Now, I was in the finals! This is why Stotz and his family made the l 7-hour drive from Illinois.

Pro Street finalists were called to the staging lanes at 6:30 p.m., but the Nxt Level crew' was still hip-deep in an engine swap. What a scene. The Velocity crow d and Slowe supporters wanted us to run on schedule, while the Nxt Level and Sprout fans were willing to wait all night if necessary. We agreed to be the last Pro class. Later, we w'ere told that w’e would run after the next round of semi-pro bikes. That, of course, caused an uproar among the Slowe fans.

As tempers flared and the track continued to cool, Stotz and I pulled an AMA official aside and told him, “Let’s be clear on this: We’ll run when you tell us to run.’’

I felt for Sprout, but I wanted to play the role of Cinderella and win my first drag-race national at age 47. And that’s what happened. Sprout couldn't respond when he was called to the line, and I short-shifted to a 7.35 at 192 mph but left my mark with a .007 reaction time.

In the end, Slowe w'on the title by three points, but Nxt Level’s Sprout and Domingo will be back. So will Kent and Frankie Stotz-on the Honda that w'on the XXX Racing Fuels AMA Dragbike World Finals. □