Invisible speed

TDC

Kevin Cameron

DORNA, ONE OF THE SEVERAL INFLUENtial groups behind MotoGP, has announced that for the 2009-2011 seasons there will be a single tire supplier: Bridgestone. Michelin, which invented the radial tire in 1948 and in 1984 made it practical for motorcycles, will be out of the series for at least that period.

Needs for increased safety and lower costs are cited as the driving force behind this change. A realistic appraisal suggests that management was unwilling to wait longer for Michelin to overcome the problems that have made some of its riders less competitive lately. With smallish MotoGP starting grids of 18-19 riders, Doma imperatively needs all the top men in the leading group, fighting for the win.

It should be explained that a “spec tire,” or single tire supplier, does not mean that only one tire will be available. Rather, the same menu of compound/construction choice will be offered to all riders, and the single manufacturer will provide a range of tires tailored by past experience to each event. It is rumored that each rider will receive 20 tires per GP, or about two-thirds the number provided in the recent past.

The safety issue voiced by riders is that of rising corner speeds. Higher corner speed has been the natural result of Dorna’s reduction of MotoGP displacement from 990 to 800cc that took effect in 2007. That change, too, was officially undertaken for reasons of “safety”-the 990s were, it was argued, just too fast. It was at that time pointed out that no one crashes on the straightaway where such higher speeds are reached. They crash in the corners.

MotoGP tire design in 2006 turned to radically lower inflation pressure in search of larger, grippier footprints. Lower pressures were a long-term trend, but the precipitating event was a request by Honda to Michelin for more traction at the end of 2005. Anyone who watches these events can see the dramatically increased angles of lean now achieved. Riders noted that higher comer speeds may mean existing gravel traps are no longer wide enough to keep crashing men and machines from hitting the outer wall.

Do spec tires reduce costs? As major teams receive their tires without cost under sponsor agreements, it is only the lesser teams who will be affected.

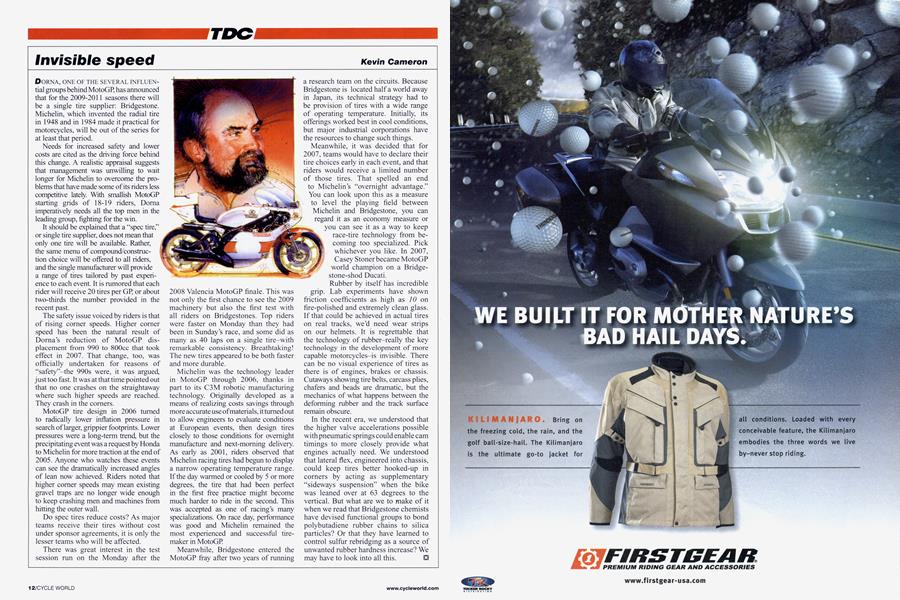

There was great interest in the test session run on the Monday after the 2008 Valencia MotoGP finale. This was not only the first chance to see the 2009 machinery but also the first test with all riders on Bridgestones. Top riders were faster on Monday than they had been in Sunday’s race, and some did as many as 40 laps on a single tire-with remarkable consistency. Breathtaking! The new tires appeared to be both faster and more durable.

Michelin was the technology leader in MotoGP through 2006, thanks in part to its C3M robotic manufacturing technology. Originally developed as a means of realizing costs savings through more accurate use of materials, it turned out to allow engineers to evaluate conditions at European events, then design tires closely to those conditions for overnight manufacture and next-morning delivery. As early as 2001, riders observed that Michelin racing tires had begun to display a narrow operating temperature range. If the day warmed or cooled by 5 or more degrees, the tire that had been perfect in the first free practice might become much harder to ride in the second. This was accepted as one of racing’s many specializations. On race day, performance was good and Michelin remained the most experienced and successful tiremaker in MotoGP.

Meanwhile, Bridgestone entered the MotoGP fray after two years of running

grip. a research team on the circuits. Because Bridgestone is located half a world away in Japan, its technical strategy had to be provision of tires with a wide range of operating temperature. Initially, its offerings worked best in cool conditions, but major industrial corporations have the resources to change such things.

Meanwhile, it was decided that for 2007, teams would have to declare their tire choices early in each event, and that riders would receive a limited number of those tires. That spelled an end to Michelin’s “overnight advantage.” You can look upon this as a measure to level the playing field between Michelin and Bridgestone, you can regard it as an economy measure or you can see it as a way to keep race-tire technology from becoming too specialized. Pick whichever you like. In 2007, Casey Stoner became MotoGP world champion on a Bridgestone-shod Ducati.

Rubber by itself has incredible Lab experiments have shown friction coefficients as high as 10 on fire-polished and extremely clean glass. If that could be achieved in actual tires on real tracks, we’d need wear strips on our helmets. It is regrettable that the technology of rubber-really the key technology in the development of more capable motorcycles-is invisible. There can be no visual experience of tires as there is of engines, brakes or chassis. Cutaways showing tire belts, carcass plies, chafers and beads are dramatic, but the mechanics of what happens between the deforming rubber and the track surface remain obscure.

In the recent era, we understood that the higher valve accelerations possible with pneumatic springs could enable cam timings to more closely provide what engines actually need. We understood that lateral flex, engineered into chassis, could keep tires better hooked-up in corners by acting as supplementary “sideways suspension” when the bike was leaned over at 63 degrees to the vertical. But what are we to make of it when we read that Bridgestone chemists have devised functional groups to bond polybutadiene rubber chains to silica particles? Or that they have learned to control sulfur rebridging as a source of unwanted rubber hardness increase? We may have to look into all this.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

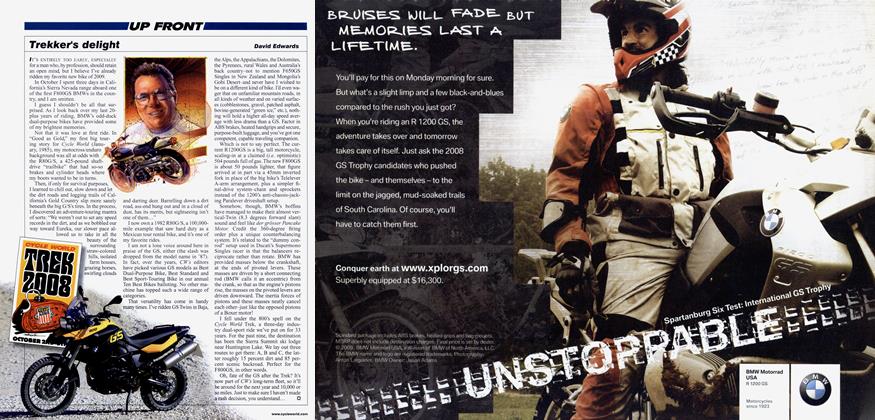

Up FrontTrekker's Delight

February 2009 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsArt And the Motorcycle Museum

February 2009 By Peter Egan -

Giro Heroes

Giro HeroesHotshots

February 2009 -

Departments

DepartmentsNew Ideas

February 2009 -

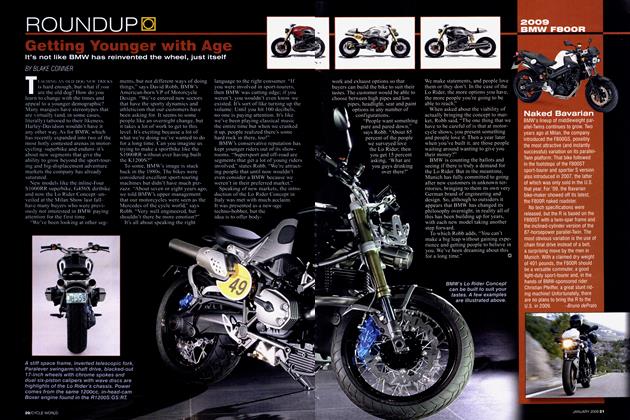

Roundup

RoundupGetting Younger With Age

February 2009 By Blake Conner -

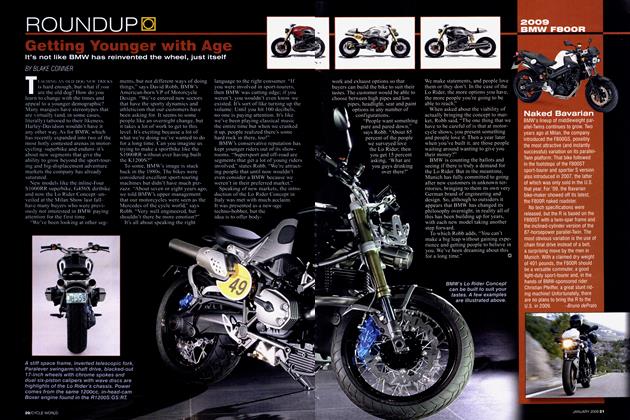

Roundup

Roundup2009 Bmw F800r

February 2009 By Bruno Deprato