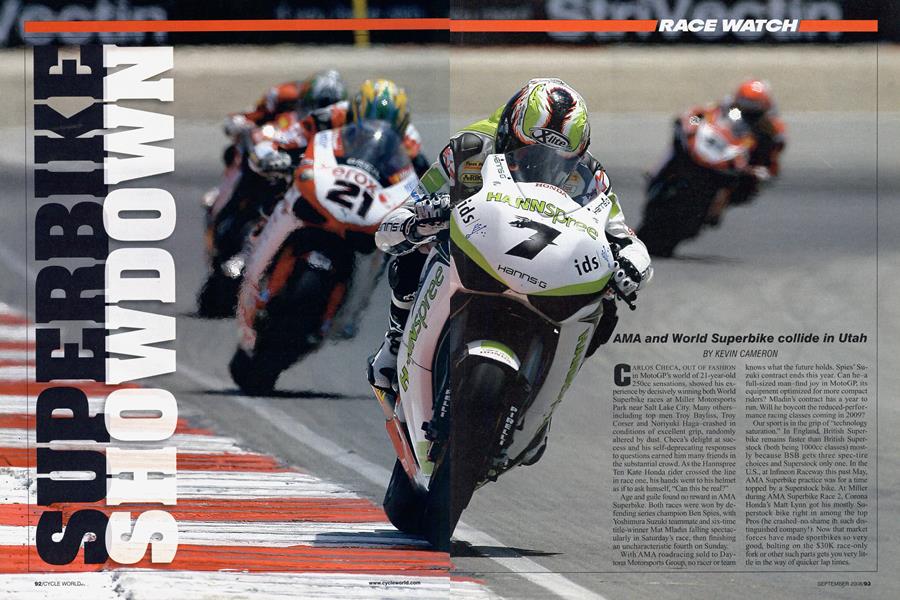

SUPERBIKE SHOWDOWN

RACE WATCH

AMA and World Superbike collide in Utah

KEVIN CAMERON

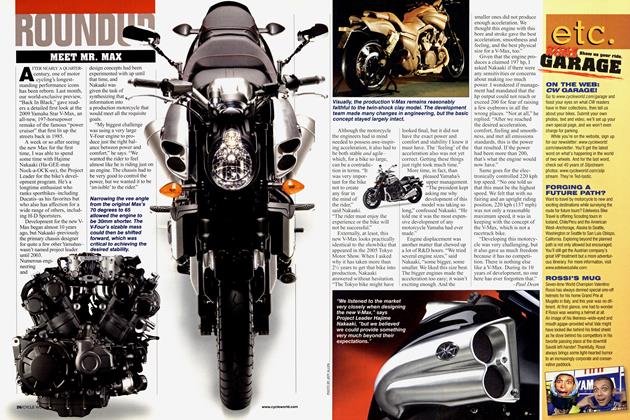

CARLOS CHECA, OUT OF FASHION in MotoGP’s world of 21-year-old 250cc sensations, showed his experience by decisively winning both World Superbike races at Miller Motorsports Park near Salt Lake City. Many othersincluding top men Troy Bayliss, Troy Corser and Noriyuki Haga-crashed in conditions of excellent grip, randomly altered by dust. Checa’s delight at success and his self-deprecating responses to questions earned him many friends in the substantial crowd. As the Hannspree Ten Kate Honda rider crossed the line in race one, his hands went to his helmet as if to ask himself, “Can this be real?” Age and guile found no reward in AMA Superbike. Both races were won by defending series champion Ben Spies, with Yoshimura Suzuki teammate and six-time title-winner Mat Mladin falling spectacularly in Saturday’s race, then finishing an uncharacteristic fourth on Sunday.

With AMA roadracing sold to Daytona Motorsports Group, no racer or team

knows what the future holds. Spies’ Suzuki contract ends this year. Can he-a full-sized man-find joy in MotoGP, its equipment optimized for more compact riders? Mladin’s contract has a year to run. Will he boycott the reduced-performance racing classes coming in 2009?

Our sport is in the grip of “technology saturation.” In England, British Superbike remains faster than British Superstock (both being 1 OOOcc classes) mostly because BSB gets three spec-tire choices and Superstock only one. In the U.S., at Infineon Raceway this past May, AMA Superbike practice was for a time topped by a Superstock bike. At Miller during AMA Superbike Race 2, Corona Honda’s Matt Lynn got his mostly Superstock bike right in among the top Pros (he crashed-noshame ih such distinguished company!) Now that market forces have made sportbikes so very good, bolting on the $30K race-only fork or other such parts gets you very little in the way of quicker lap times.

Fellow CW editor Matthew Miles and I somehow won a lottery to be “embedded” in the Yamaha Motor Italia garage. We became flies on the wall, able to observe all that was done on the bikes of Haga and Corser. It was an education.

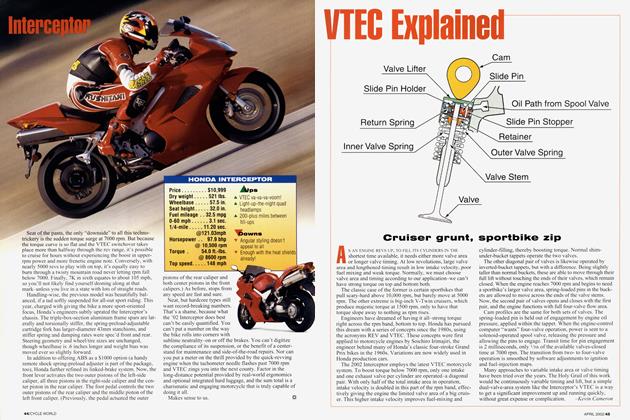

The Yamahas have wet clutches, and when they were first started, we could hear the chatter of the plates’ drive tangs. As the oil circulated, the clatter quieted down. On the Ducatis, noise from their dry clutches is much louder than the desmo valve drive. Here on Corser’s Yamaha is an Öhlins TTX25 fork, with its pressure-accumulator cylinders on the bottom bracket, behind the fork tube. Haga’s bike has a “through-rod” fork, whose dampers are built like steering dampers-the operating rod goes in through one seal on one end and comes out another at the opposite end. Result? Constant internal volume, so there is no need for a pressure accumulator. I asked the Öhlins engineer why the difference.

“Riders like to have something special,” he said. “But performance is about equivalent.”

The teams began here with good gearing and setup information; I never saw Corser’s crew (each rider has six technicians) remove the rear suspension unit or change the fork. In the old, pre-TTX days, there would have been at least one damper-valve washer re-stack. Seriousfaced team manager Massimo Meregalli told us that each rider has a crew chief, a “data guy,” three mechanics and a suspension tech. There is also a computer specialist, unseen in the back room.

As we walked pit lane, contrasts were big. One small team with a lone bike works in a bare garage. Next to them is a big team whose first act at every track is to unroll and smooth carpeting, then carry in and erect graphic wall panels with corporate logos and images. Then equipment is brought in. The only face such teams present to the world is a perpetual photo op. I

Everyone these days seems to have Brembo Monoblocco calipers, made from a single piece of aluminum so smoothly and perfectly machined that it appears to come from another planet. Somehow a special right-angle boring head fits into the disc gap so that the four piston bores can be created and highly finished. Careful measures are taken to prevent pad heat from traveling through the ventilated hollow pistons to the brake fluid. Yamaha has long used quick-detach hydraulics to facilitate dry/wet changes in Grand Prix racing. The master cylinder joins a junction through what looks just like an old BNC coaxial cable connector.

Carbon-carbon brake discs are not legal in World Superbike so these are iron, their pad tracks very narrow to keep heating rates at the inside and outside diameters similar. Where is the toothed wheel to supply data for traction control? Old hat! Today a row of many tiny magnets is pressed into either the brake disc carrier or a separate plate. They give a powerful signal and are nearly invisible.

When a Yamaha tank is off (allowed to be enlarged to 23 liters, usually by projecting a “foot” backward under the seat), you can see Marelli electronics carried on a carbon-fiber shell, quickly detachable from the rear of the airbox. When the top of the airbox is lifted, there is a wedge-shaped air filter, then the row of large, blue plastic intake bells. The fuel injectors are below. What is that little 2-inch gizmo high on the left side of the engine? It’s a Marelli alternator, extremely compact because of the power of its rare-earth magnets-and rumored to cost as much as a small economy car.

Because we are used to cars and bikes that never “use” any oil at all, it was interesting to see 200cc of gray-green oil being added to each of Corser’s engines after many laps of use. Why? If the oil scraper ring is too effective, friction of the single top ring might rise. Maximum power and durability require getting all these details right.

Fuel consumption on the outer course (3.048 miles) was about 16.5 mpg for the Yamahas, making finishing races a non-issue, very much in contrast to MotoGP, in which machines often run out on the cool-down lap. When you look into the exhaust of an AMA Superbike, you see the light cream color of lead oxide, for leaded race gas remains legal in the class. There is no color in the end caps of the WSB machines, which have burned nolead race gas (a very specialized technology) for years. Upon one of Haga’s returns to the Yamaha garage from Saturday practice, it took time to realize that he’d broken his collarbone. After a conference, he decided to continue, strapped up and iced down. Corser, helmet still on, went to his pit-box chair after each practice, closely attended by his data man and crew chief. They would then methodically review the handling and other problems encountered, making an action plan turn by turn.

Tires could be seen on racks in the back room, each wrapped in its warmer, onlight gleaming. New examples were brought out and rears were changed more often than fronts. This is a different world because WSB is a spec-tire series, using Pirellis. Pirelli race manager Giorgio Barbiere explained to assembled journalists Saturday morning that teams receive 15 rears and 11 fronts, chosen from a sheet issued to teams each pre-race Thursday.

“Spec tire” does not mean that everyone uses the same tire, but that all choose from the same menu and no one receives “specials.” This allows the tire-maker to use racing for technology development without favoring individuals. There is a system in place by which tires are doled out to users by series promoter FGSport, not by Pirelli, preventing any possible favoritism. Each used tire is by a team sticker. At first, used tires were laid out on the ground post-race for all to inspect. But when confidence in the fairness of the system had been established-“Hmm, I guess he beat me on the same tire that I used”-nobody came. There are three pre-season tests at which the majority rules in choice of new types to be produced for the coming season. This prevents tires from being developed for specific machines.

It’s interesting to compare typical tire pressures. I asked Barbiere about the very low pressures now being used in MotoGPin the range of 12-15 psi. He replied that there are two separate development streams now: one specialized for MotoGP and the other tied to the original-equip-

ment market. Dunlops in AMA Superbike are running at 17-22 psi, but we watched pressure gauges in the Yamaha Italia pit indicate 27 cold, 31 hot for Pirelli rears. Why low pressures? The lower the pressure, the bigger the footprintand the softer and grippier the rubber that can survive on it.

We had a 20-minute interview with Bayliss, who will retire at the end of this season. Asked about the new 1198cc Ducati he is riding, he first noted that, “The (previous) 999 was the best bike I’ve ever ridden in my career,” and then that, “a bit more grunt out of the corners has put us back on par with the others.” Previously, four-cylinder 1000s competed at a moderate level of tune, while lOOOcc Twins were allowed to make up for their lower rpm capability by a higher (and very expensive) tuning level. Ducati lobbied for the cheaper tuning level of the Fours, with the rpm difference made up by 200cc of additional displacement.

The new bike, he observed, needed a lot of work to make it good, but, “at the first race it shocked everybody ’cause we were on the pace.” And they have stayed on it. Even with no points scored at Miller, Bayliss had 194 points vs. double-winner Checa’s 166.

I asked Bayliss if spec tires chosen by a majority of teams imposed a handicap on Ducati-the only Twin currently in the series. “I think honestly all the tires suit all the bikes,” he replied. He then described following Haga last year at Misano in Italy, and seeing the Yamaha do the same things that the Ducati would have done if it were ridden in the same fashion.

His views on traction control? “I had a couple moments today,” he admitted. “Traction control helps over race distance. But you have to really work the throttle. It does help you exit; it gives you a bit more confidence. Once you’ve got the bike up and the gas on, you’re going to highside very, very rarely. You crash because of too much corner speed-nothing’s going to fix that-or at the first touch on the gas when you’re right on the side and so close to the limit of adhesion.”

Crossing the paddock we ran into Roger Edmondson, one of three principals of DMG and planner of AMA racing’s future. Details of the new classes-“Daytona Superbike” and “Liter Bike”-emerge slowly. There will be spec tires and fuel (if you are currently outraged by $4 at the pump, consider that some racing “gasolines” have sold for as much as $500 a gallon). Both Dunlop and Pirelli seek to be the tire supplier.

As always in the 20 years I have known Edmondson, his speech was carefully organized and articulate. He is affable but inscrutable, giving nothing away in such casual encounters, yet emphasizing firmly that the new series will be made to succeed. DMG has the means to correct U.S. roadracing’s biggest problems: lack of promotion and inconsistent presence on television.

The speed of Jamie Hacking’s Kawasaki was the AMA Superbike shocker. Despite running off early in both races (shades of his early career!), the Hacking/ Kawasaki combination charged through to second in both races, even chewing threateningly into Spies’ lead in race two. A circumspect Neil Hodgson took two thirds-good finishes for the built-inAmerica Hondas. Just as DMG is stuffing this class into history’s trashbin, it shows new vigor. >

Moments before the start of the first World Superbike race came the exodus from the grid-streaming mechanics, startcarts and well-wishers funneling through the wall. Almost immediately, Regis Laconi, Haga and Bayliss crashed, and Checa

pushed to the front with a combination that let him execute plans while others merely coped. Late in the race, Corser and Bayliss’ Ducati teammate Michel Fabrizio moved past early leader Max Neukirchner on an Alstare Suzuki.

Race two was equally mysterious. Where did Checa’s extraordinary stability come from while others crashed? On lap 1, Bayliss led, pulling a gap, with Checa eighth. Small battles up front became irrelevant as only a few bikes had the grip to hold top positions. At the end, it was Checa again by nearly 4 seconds with Neukirchner on a similar bike-a Japanese inline-Four-second and Ducati-mounted Fabrizio third. Corser had lost the front (“There was no warning”) and crashed during his attempt to stay clear of the advancing Fabrizio. His teammate Haga, despite his broken collarbone, conservatively managed his assets to be sixth behind Max Biaggi. Bayliss had slowed with mechanical problems.

Why were the Ten Kate Hondas so fast here? No clear answer emerged, but their ability to use a softer front suggests these smaller, lighter 2008 bikes could make stronger corner exits, hold line and not run wide onto dusty and less-grippy pavement.

The weekend presented onlookers with two prospects: World Superbike is a popular, competitive series with several top teams and riders. It is based upon production bikes with limited engine modifications. Its presentation is designed to engage the crowd and bring the riders to the fans-we saw this work in the well-attended post-race rider interviews, which are not limited to the press. WSB also changed a lot of minds by its successful 2004 adoption of spec tires, which have improved competition.

Many American fans wonder why World Superbike rules are not adopted here, but American rules-makers have always shied away from being part of anyone else’s series. This is despite Superbike having originated here then morphing into World Superbike once it took root in Europe.

What paths are about to be taken by DMG with AMA racing? Daytona Superbike starts with 600s limited to 140 hp and adds such machines as the BMW HP2, Buell 1125R and Triumph Daytona 675. It aims to break the sameness of the four-cylinder establishment and prevent the major factories from making unlimited power. Liter Bike sounds a lot like Superstock. Even its existence is encouraging, for it reveals that there has been consultation between DMG and the manufacturers (who want most to promote their profitable 1000s).

There is no better, cheaper or more available basis for racing than the production sportbike of today. How best to apply that to the problem of creating a major sport remains an open question.□