MARK HOYER

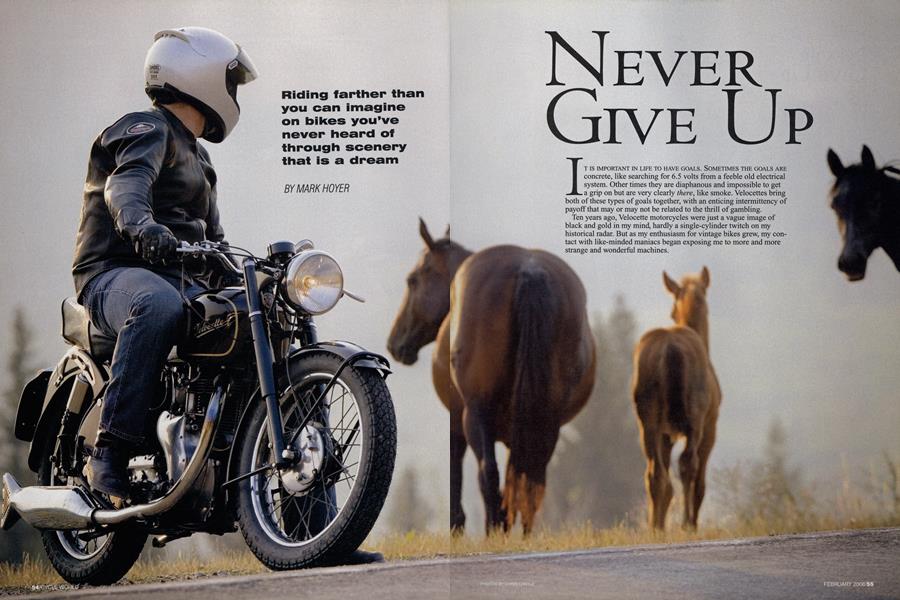

NEVER GIVE UP

IT IS IMPORTANT IN LIFE TO HAVE GOALS. SOMETIMES THE GOALS ARE concrete, like searching for 6.5 volts from a feeble old electrical system. Other times they are diaphanous and impossible to get a grip on but are very clearly there, like smoke. Velocettes bring

both of these types of goals together, with an enticing intermittency of payoff that may or may not be related to the thrill of gambling.

Ten years ago, Velocette motorcycles were just a vague image of black and gold in my mind, hardly a single-cylinder twitch on my historical radar. But as my enthusiasm for vintage bikes grew, my contact with like-minded maniacs began exposing me to more and more strange and wonderful machines.

CON

The more I heard Velocettes run and the more I read about them, the more impossible it became to resist owning one.

But search as I might, I couldn’t find one Velocette dealership in the greater L.A. area. Turns out the factory shut down in 1971, although the English company still exists and produces spare parts, carrying on the motorcycling tradition started circa 1905. Company founder was a transplanted German called Johannes Giitgemann who initially adopted the name John Taylor, then later John Goodman. The earliest bikes were marketed under the name Veloce, but the first truly successful model was the 206cc Velocette (simply meaning “little Veloce”), and the name stuck. So, English bike, Italian name sometimes mistaken for French, German founder with a couple of aliases.

The K-series ohc 350cc models made a name for the company in the mid-’20s, and the demand for bikes after a KTT’s win at the Isle of Man in 1926 prompted a move from Velocette’s small facility to larger quarters at Hall Green, still in Birmingham, where the company stayed for the duration.

It was the later, more profitable and easier-to-build pushrod MAC 350 and MSS 500cc Singles-and their higher-performance Viper and Venom variants-that the company survived on for so long.

My ago 1954 while MSS I was 500cc on holiday came to in me New about Zealand. four years It needed an engine rebuild, so I had a mechanic down there do the job, then returned eight months later and took a 1000-mile tour around the South Island before I shipped it home.

The “rebuild” wasn’t quite what a fellow would hope for, and the bike has suffered a string of troubles starting with a piston seizure on the New Zealand tour. So, ever since I got the MSS stateside I’ve been trying to have it ready to ride on the Velo club’s annual Summer Rally. Finally, this past summer, both my schedule and the health of the bike coincided favorably with the ride dates. The tour of Montana would take us through Glacier National Park and surrounding areas, plus a spin into Canada, and so the club called it the Big Sky Rally.

Getting the bike ready wasn’t a small undertaking-new piston, cylinder, wiring harness, tires, brakes, generator, carburetor, ammeter and more-but the MSS was finally ready again for a long ride. Or so I thought.

The Velocette Owner’s Club of North America has 250 members in the States, with about 70 more located abroad. Their motto is, “Proper Motorcycles. Real Riders.” You might take this as so much posturing, but for 25 years these people have been hitting the road during the summer to ride their Velocettes 1000 miles during the course of a week, many members camping along the way. Some folks also ride to and from the event on their Velos. A group this year rode from Los Angeles to Montana and back home again, adding roughly 3400 extra miles to the planned route. In other words, they are a little bit crazy, but only in the most admirable way.

I’m not so nuts, at least not with my less-proven bike, so I packed the CW van with my friends Bill and Marla Getty, who brought their 1964 Venom Clubman. Bill used to run a British bike repair shop, and despite the incredible job security, gave it up to go work in the wholesale parts business. But because of his experience working on all kinds of Britbikes, day in and day out, he’s pretty handy to have at roadside when there is an unforeseen problem. Or problems.

I’d admired this club for quite a while, having met a few of its members over the years. Bruce Farren bought my ’75 Laverda 3CL several years ago, and is also the guy who first let me ride a Velocette. Paul Zell, Paul d’Orleans, and Pete and Kim Young had all been regulars at CWs Sonoma Rolling Concours events. They’re all real riders and have lots of proper motorbikes, even if some of them aren’t Velocettes.

As I met the rest of the club members attending the rally and had a look at the 40 or so ready-to-go Velos on site, I realized that most of the other folks in the club were much like the ones I’d met before. Everybody came to ride.

Home base was Symes Hot Springs in southwestern Montana. We arrived late on a hot afternoon, with a mass departure the next morning. By “mass” I mean that at

least one of us was praying. In any case, after two long days in the van breathing race-gas fumes (“cheater” fuel, I later learned...), Bill and I decided to go for a quick shakedown spin. It was all glory and light. The sun was getting low and casting a golden glow as we descended a long hill into a wide farming valley. My bike had never run better and never seemed more ready to go than at that moment.

Unfortunately, a moment after that, my main (only) fuse blew and

the lights went out. Still, because the sun hadn’t quite set and the bike gets its spark from a magneto, I could ride back to camp to investigate. Really, all my goals had come together at that point: 6.5 volts, an indescribable feeling, then smoke. Perhaps I should have quit then.

But there was a lot more great stuff to come over the next week. Rally planning is undertaken as the main duty of the club president, in this case Matt Young (brother to Pete). He was riding a Norton Commando this year, but by rally’s end had made a deal for a Viper, the high-performance version of the 350cc MAC. Wisely, he’d planned the first day of the rally as a 200-mile loop, allowing mechanical bugs to be worked out in a known location where everybody’s vehicles (with parts, tools, etc.) were parked. Some people patched gas tank leaks, others adjusted primary chains and I wiped off spilled battery acid and replaced a couple more blown fuses while searching for the cause.

It riding was during rally moment. this time Bill that had I had checked my quintessential his primary-chain nontension and left the cover off of the inspection hole so he would remember to fill and adjust it after the bike cooled. I was tracked down by not one but two concerned members who had, irresistibly, stuck their fingers into another man’s motorcycle...

Once we gathered around Bill’s bike, it prompted discussion about the proper amount of primary-chain tension-and then, of course, we had to check my primary-chain tension. After that, somebody sat on my bike and checked the finaldrive chain. As he moved it with his hand, three different people spoke nearly at once: “It’s too loose,” “It’s too tight” and “It’s just right.” We all laughed heartily, grabbed another beer and I left my chain tension alone.

Our first point-to-point stage ran from Symes to St. Mary, a 210-mile run. It was an awesome sight to watch the bikes get packed up for the ride and then pound out of town with their characteristic tight, staccato beat.

This also marked the day that I learned the most important part of the rally: Never give up. The greatest success is finishing, and everyone on the rally will do their utmost to help you make it to the end.

Good thing. After lunch, perhaps 300 miles into the week and just 700 more to go, the MSS became very hard to start. Once out on the road again, it only took a few minutes for me to realize something was wrong, so I scanned the side of the road for a shady place to pull over and work. MSS magnetos of my bike’s era were often fitted with Automatic Timing Devices that are riveted to the magneto’s driven gear to advance spark timing as revs rise. Stock gears were made of a dense fibrous material, but these are notorious for failure. Which is why I had replaced mine with a supposedly unburstable steel gear. But when I pulled off the timing cover at roadside, I found seven teeth stripped clean off.

After a voyage of discovery, all the missing teeth were recovered from the timing chest or the sump. One worries about steel gear bits ending up in the main bearings, for example.

“Here, you can have this,” said Paul d’Orleans, who had pulled up in the chase truck. “I hate ATDs. All my bikes have manual timing.”

In his hand was an advance unit on a fiber gear, my ticket to ride, right out of the spares he carried in his van. After reassembly, the bike fired right up. I was saved!

Paul was four-wheeling because he’d had the front wheel lock unexpectedly on his Clubman just a half-day into the rally. “Who ever heard of a Velo locking its front brake?!” he recounted later. The mechanical issue that caused the trouble was unsolved and Paul’s body was a bit worse for wear, too. But he had gotten himself up and limped man and machine to the hospital! He was sore and the bike was toast. Of course, once your bike is out, its parts are pretty much up for grabs, which meant the crooked Clubman was then pilfered of bits and pieces for the remainder of the rally. “That thing is going to look like a holiday turkey at the end of the meal,” quipped Bill.

It hadn’t taken long, because the magneto was stripped off the bike while it was still warm by Jeff Scott, whose Endurance scrambler model liked to eat magnetos the way my bike munched on timing gears. To Jeff’s credit, he had ridden 1300 miles to get to the rally and did finish.

In light of my engine trouble, Bill and I short-circuited the route, which called for a long loop around the south end of Glacier National Park. Instead, we climbed Going-to-the-Sun Road, which was a straighter shot to the next hotel. Although the skies were hazy from various wildfires burning around Montana in this hot, dry summer, the scale of the landscape was overwhelming and at least got my mind off the phantom knocking noises I kept hearing from my untrustworthy powerplant.

That thought night I in was St. hearing Mary, I with brought a group up the of Velo bad sounds fellows. I “The farther away from home you get, the worse your bike will always sound,” said Mike Jongblood, one of the guys who had ridden from L.A. His practical, experienced voice is widely consulted in the club, as are his skills fixing sheetmetal, and most other things.

In fact, the level of expertise in the whole club is pretty astonishing. As the sun was setting, we walked up to Cory Padula and Paul Zell, who had been working on Mavis Shafer’s Venom. Cory runs a prototyping shop with all kinds of fancy machine tools and the like, and in his spare time designed an electric starter and alternator to fit pushrod Velos.

“What’s going on?” asked Bill.

“One of the poles on the alternator was bad, so we wired around it,” replied Paul, who also had engineered his own estart system for his bike.

visit www.cycleworld.com

“Of course you did!” exclaimed Bill with an incredulous laugh.

“That’s what I would have done,” I said, rolling my eyes

my in disbelief. But they were just doing their thing.

Lots of other folks were just riding their bikes and arriving at the hotels relaxed with not a bit of grit under their fingernails.

Keith Hogland had a built-fromscratch Thruxton that looked as stunningly clean and wonderful on the last day of the ride as it had the first. Even the rally veterans were impressed. Club chairman John Ray, survivor of the first rally 25 years ago, was always relaxed and gracious, his super-clean Venom Clubman seeming ever at the ready and as reliable as a Honda.

e rode on with a big loop through Canada to Waterton Park that offered more jaw-dropping scen-

ery and empty roads. Once back in the U.S. (bring your passport!), we took up luxury accommodations at the Ksanka Hotel and Mini Mart. After a long hot day on the Velo, plus the time spent sitting in the sun at the border, even the Ksanka’s lumpy mattress felt great. Plus side was all the malt liquor and snack meats you could wish for, mere steps away.

The bike was feeling good, but there is another but. That same sickening pop-stutter-pop returned as we left Ksanka in the morning. The borrowed fiber gear had stripped. Where would we find another ATD? Jongblood rolled up with his crew, but shook his head in the negative. Larry Luce, part of the L.A.-MontanaL.A. group who was riding a really original MSS, pulled a magneto from his bag. Though it had no gear, we took it just in case. Luckily for me there were enough fallen soldiers at this

point that the chase truck driven by Zuma Ross and carrying her husband Tom’s MAC (with a cracked frame) pulled up. Tom offered his steel-geared ATD, while Bill poked around and found that my BTH magneto had a loose shaft, which was what was killing the gears. He removed a couple of shims, the bearings lost their unhealthy play and I finished the rally on my third mag gear, a club record.

Thank goodness the bike was running again, because the best road was yet to come. There is a 40-mile stretch of Highway 37 along Lake Koocanusa that was positively unreal, with loads of elevation changes and tight comers. In modem terms, Velocette frames are laughably flexible and the brakes

are amusingly ineffective. For

their era, these bikes were quite sweet handling, and given the proper mindset are still a great pleasure to ride on a winding road, even if it is a bit of work.

Just about the time you start feeling heroic for riding your 50-year-old bike so far and what feels like so fast, you come across people riding rigid-frame, girder-fork, prewar machines. Kim and her husband Pete Young are rally stalwarts. They brought both of

their young kids, Sirisvati and Atticus, along for the ride. Kim was riding solo aboard a 1930 KSS, the oldest bike on the rally. Pete, often with one of the kids, rode a sidecar-equipped rigid MSS. That, my friends, is the teaching of proper family values.

values.

David Poole was visiting from England and also on a prewar KSS borrowed from John Simms. John Ellis, an English expat now living in California, was riding his ’37. The bike had lived most of its life in England. How original is it? “I honestly believe the oil was from 1950,” he says. “I took the drain plug out and it wouldn’t flow!” The bike was last registered in 1962, and once in John’s hands it was treated to a “sympathetic” restoration, which is to say left mostly original but with rebuilt engine and other mechanicals.

Every passing mile brought mixed feelings. Part of me was happy that my bike was still going and that it seemed as though it would make the finish. The other part of me realized that the finish was the end of life on the road in such good company. ’Course, if I had known how excellent the post-rally party and Annual General Meeting was going to be, I would have ridden faster-your typical club AGM is a pretty dry affair, but this was not, ahem, dry.

The post-rally Concours d’Oiligance winners were announced-Keith Hogland’s stunning Thruxton was a shooin for Most Outstanding Velocette-and other more or less serious awards were addressed. The Iron Butt went to Mike Jongblood, Larry Luce, Neville Smith and David Morse, the crew that had ridden from L.A. and were riding back starting the next morning. The most anticipated award is the “Crock,” given to a bike that failed to finish the rally. Let’s just say it is not a crock of gold. Paul d’Orleans, though first out, couldn’t win, if only because enough parts of his bike did finish the rally, just on other people’s machines! Instead, it went to Tom Ross and his MAC with its cracked frame. All I can say, Tom, is thanks, because your bike’s mag gear allowed me to finish the ride. (Back at the office, Canet pointed out I should have offered Tom my frame. Didn’t think of that one!)

My prize? A blue safety reflector on a stick, so I could drive it into the ground when I inevitably pulled over at roadside to fix my bike.

Even proof though that a I’d well-sorted had my share (or not of so trouble, well-sorted) this rally was vintage Single can make the distance, especially when surrounded by such an excellent support group.

After 1000 miles, I had attained all the goals I’d set out to achieve. Following the rally, I discovered my primary chain was about to let go and the clutch had started slipping quite a lot. There was also the problem of the bent connecting rod...

That has been the beauty of my Velocette ownership over the years: There are always more concrete goals. But by learn-

ing from my fellow club members to never give up, to never surrender, it allows me to attain those ineffable, precarious moments in life when everything seems right and there is no greater freedom than being able to

tor next on. time, But I’ll just bring in case. the blue reflec-

END

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontElectric Chair

February 2008 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Road To Harleysville

February 2008 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCControlled Motions

February 2008 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2008 -

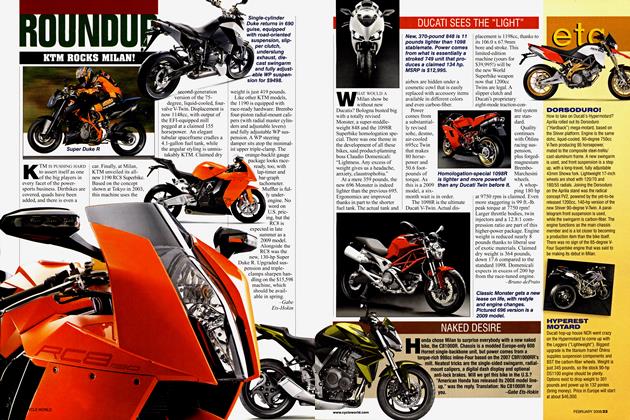

Roundup

RoundupKtm Rocks Milan!

February 2008 By Gabe Ets-Hokin -

Roundup

RoundupNaked Desire

February 2008 By Gabe Ets-Hokin