Anglo-American

UP FRONT

David Edwards

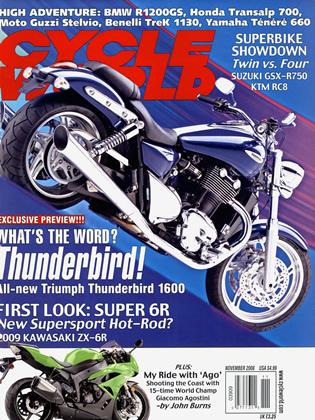

So, SOME 18 YEARS AFTER TRIUMPH WAS reborn, it’s taking on Harley & the Vee Gang with a whacking great cruiser, the Thunderbird, at 1600cc the biggest inline-Twin ever.

’Bout bloody time, mates.

It’s only fitting that Triumph get serious in this most American of motorcycle classes. See, the original Triumphs may have been bolted together between tea breaks in Merry Olde England, but they were really “made” in America.

All due respect to St. Edward of Turner-legendary designer of the 1938 Speed Twin, later to become Triumph’s chief designer and managing director-but if it were left up to him, Triumphs might never have grown past 500cc. And the less said the better about the man’s affection for tanktop parcel grids (a.k.a. “gonad-strainers”), goofy, saucer-like headlight nacelles and, worst of all, semi-enclosed rear “bathtub” bodywork.

No, it was Americans who made Triumphs the coolest two-wheelers ever. Brando rode a Triumph-at least on celluloid. In real life, James Dean chased starlets on a Triumph. Steve McQueen bounded across the Mojave on a Triumph. Evel Knievel was on a Triumph for his ill-fated flight over the fountains at Caesar’s Palace.

Because we rode mainly for fun, Americans demanded more power from more displacement-first a bump to 650cc, then to 750. U.S. speed merchants hopped-up the engines even further, attacking the salt flats at Bonneville, giving Triumph a beloved model name and its “World’s Fastest Motorcycle” slogan. Those first 650s, like the new 1600 cruiser, were called Thunderbirds, a name borrowed from American Indians. Later 500s were Daytonas, after the famed Florida speed bowl. At a time when Turner, notable for his skin-flintiness, forbade a factory race team, we gunned Triumphs to considerable glory on dirt ovals and TT steeplechases and dragstrips and roadrace courses and enduro trails and scrambles tracks.

“Triumphs may have been bom in Britain, but they were bred in the USA,” says Lindsay Brooke, author of Triumph Motorcycles: A Century of Passion and Power. “Just as Winston Churchill was halfAmerican by blood, Triumphs in the postWWII era were also heavily influenced and loved by us Yanks. We bought ’em by the boatload, then proceeded to customize, modify, race and generally flog the machines in every imaginable way on road and track.”

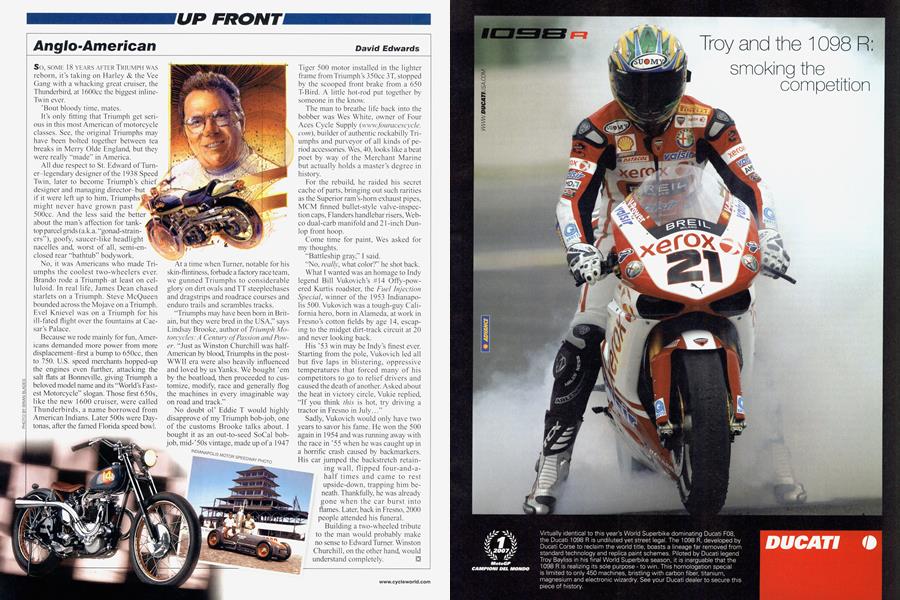

No doubt ol' Eddie T would highly disapprove of my Triumph bob-job, one of the customs Brooke talks about. I bought it as an out-to-seed SoCal bob job, mid-'50s vintage, made up of a 1947

Tiger 500 motor installed in the lighter frame from Triumph’s 350cc 3T, stopped by the scooped front brake from a 650 T-Bird. A little hot-rod put together by someone in the know.

The man to breathe life back into the bobber was Wes White, owner of Four Aces Cycle Supply (wwwfouracescycle. com), builder of authentic rockabilly Triumphs and purveyor of all kinds of period accessories. Wes, 40, looks like a beat poet by way of the Merchant Marine but actually holds a master’s degree in history.

For the rebuild, he raided his secret cache of parts, bringing out such rarities as the Superior ram’s-horn exhaust pipes, MCM finned bullet-style valve-inspection caps, Flanders handlebar risers, Webco dual-carb manifold and 21 -inch Dunlop front hoop.

Come time for paint, Wes asked for my thoughts.

“Battleship gray,” I said.

“No, really, what color?” he shot back.

What I wanted was an homage to Indy legend Bill Vukovich’s #14 Offy-powered Kurtis roadster, the Fuel Injection Special, winner of the 1953 Indianapolis 500. Vukovich was a tough-guy California hero, born in Alameda, at work in Fresno’s cotton fields by age 14, escaping to the midget dirt-track circuit at 20 and never looking back.

His ’53 win may be Indy’s finest ever. Starting from the pole, Vukovich led all but five laps in blistering, oppressive temperatures that forced many of his competitors to go to relief drivers and caused the death of another. Asked about the heat in victory circle, Vukie replied, “If you think this is hot, try driving a tractor in Fresno in July...”

Sadly, Vukovich would only have two years to savor his fame. He won the 500 again in 1954 and was running away with the race in ’55 when he was caught up in a horrific crash caused by backmarkers. His car jumped the backstretch retaining wall, flipped four-and-ahalf times and came to rest upside-down, trapping him beneath. Thankfully, he was already gone when the car burst into flames. Later, back in Fresno, 2000 people attended his funeral.

Building a two-wheeled tribute to the man would probably make no sense to Edward Turner. Winston Churchill, on the other hand, would understand completely.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue