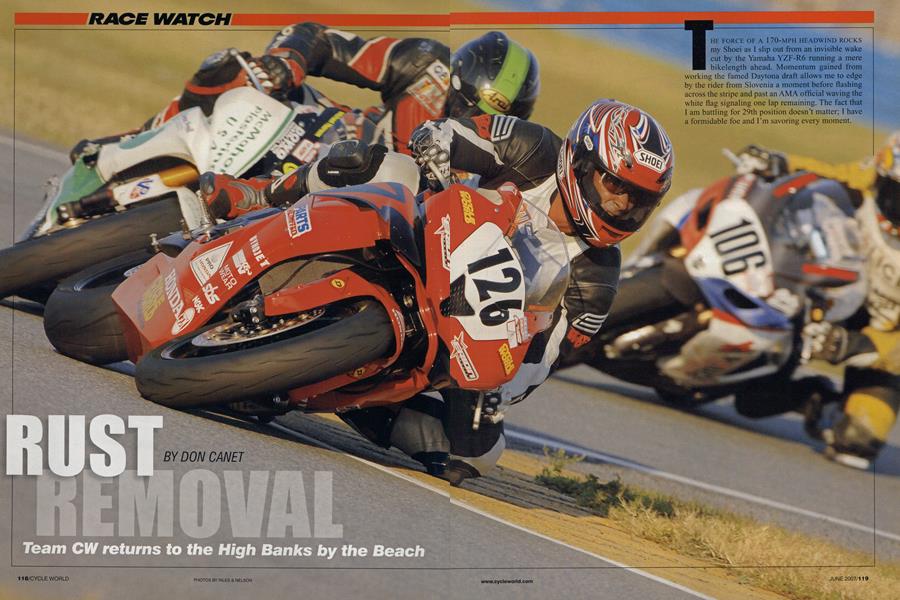

RUST REMOVAL

RACE WATCH

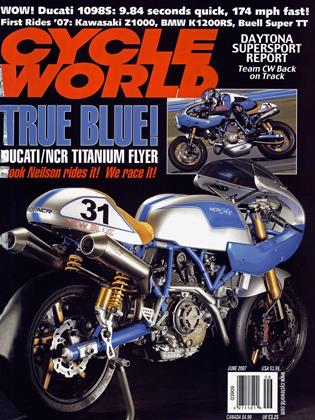

Team CW returns to the High Banks by the Beach

DON CANET

THE FORCE OF A 170-MPH HEADWIND ROCKS my Shoei as I slip out from an invisible wake cut by the Yamaha YZF-R6 running a mere bikelength ahead. Momentum gained from working the famed Daytona draft allows me to edge by the rider from Slovenia a moment before flashing across the stripe and past an AMA official waving the white flag signaling one lap remaining. The fact that I am battling for 29th position doesn’t matter; I have a formidable foe and I’m savoring every moment.

Arriving at this competitive state of mind in the 22-lap AMA Supersport finale this past March at Daytona International Speedway hadn’t come easily. While my bike, a 2007 Honda CBR600RR prepared by Erion Racing, performed superbly, reviving the drive and desire within me to not simply ride hard but to truly race took time.

Eight years ago, I competed in my last AMA professional roadrace, also a Supersport event at Daytona. Returning now as a 45-year-old father of three children—ages 7 and under-brought with it a weight of responsibility unlike any I had raced with in the past.

While conducting CW race track tests on the latest crop of sportbikes has kept my riding skills fairly sharp, there’s no substitute for the toe-to-toe tussles encountered during real competition. Bottom line, my racecraft was rusty.

Unfortunately, the only pre-Daytona seat time I acquired aboard the brandnew CBR-RR amounted to a couple hundred break-in miles I logged prior to dropping the bike off at Erion’s headquarters in Orange, California.

Assigned the task of breaking in the new Honda 600, Canet headed onto the freeway system and into the canyons with instructions to vary load and speed. The job was both boring and freezing-but nec-

essary. Rick Hobbs, Erion s crew chief, says, “On the dyno, we spend about 45 minutes, increasing load in stages of steady throttle and rpm.” Asked if like with modern car engines, the oil remains clean after break-in, he replied, ‘Actually, they shed a fair bit of material. We get 80-90 percent of (our eventual) ring seal on the dyno, measured by a blow-by gauge.” The gauge is similar to a city gas meter. —Kevin Cameron

As to be expected of any frontline race team, Erion keeps its speed secrets under wraps, but as promised, our bike received a level of preparation similar to that of the CBRs ridden by contracted team riders Josh Hayes and Aaron Gobert.

In years past, factories and top privateers took their cylinder heads to the likes of C.R. Axtell or Jerry Branch for flow and porting work. That meant hours with the die grinder. Today, in AMA Superbike, one master port is shaped by hand, then all of a team s race-head intake ports are filled with plastic and CNC milled to that shape automaticallya process I saw at work a year ago when I visited the shops of Vance & Hines, near Indianapolis. This is not legal for AMA Supersport or Superstock, where material may he removed only from the valve seat rings. -KC

Chris Smith, an American Honda service tech, was flown in to handle trackside tuning duties. Smith was provided a work area in the Erion paddock garage, and we occupied a neighboring pit-wall stall during our on-track sessions. The hospitality extended was well beyond anything I had hoped for, and my week with the team felt like a fantasy factory ride. Ten years ago, I might have gotten caught up in it all and felt as though I had to perform accordingly. Fifteen years ago, I might have even viewed it as a tryout for the team. But now, I simply didn’t want to do anything stupid that might make extra work for the hard-working crew or consume spare parts.

Smith had plenty to do, installing Öhlins race suspension, mounting Daytonaspecific Dunlop Sportmax D209GP radiais on two sets of wheels and adjusting handlebar and lever position to suit my preference. Once CW decals and my race number had been applied, the bike was rolled through AMA technical inspection for a stamp of approval.

The CW/Erion CBR600 had $2000 Öhlins fork damping cartridges, which emulate the performance of Öhlins 'race fork. At the rear, suspension was handled by one of the new Öhlins TTX dampers. This concept entered MotoGP in 2005, showed up on factory Kawasakis in the U.S. in 2006 and is now more widely

available. Traditional de Carbon pressurized dampers have used the full piston with integral washer stack for rebound damping but only damper-rod displacement (the oil pushed aside as the piston rod enters the damper) to control compression damping. The TTX design employs a solid piston (carrying no valving) to drive fluid through separate compression and rebound washer stacks, each of which is screwed into the damper body so the piston need never be removed. This design allows a robust flow for compression control, simplifies service and operates cavitation-free on a lower pressurization that further reduces stiction-generating seal grip. —KC It’s been said you meet the nicest people on a Honda, and it seems that philosophy applies to racing one, as well. Team owner Kevin Erion was calm, reassuring and reminded me more than once to “just have fun.” Feeling a tap on

my shoulder while waiting to roll out for the first practice, I turned to see Gobert grinning. “Good job with the helmet, mate!” Turns out, my Shoei was a replica of his own signature lid. Defending Formula Xtreme Champion Hayes also came over and extended a genuinely friendly offer to assist with any questions I might have about the track.

My initial practice laps were unnerving, to put it lightly. This was my first look at the revised 2.95-mile configuration adopted in 2005. Not only was I figuring out several new corners, establishing braking points and the like, I had to get acclimated to my bike’s one-up/ five-down racing-style transmission shift pattern. All the while, it seemed like every rider out there, from the factory fast guys to the scruffy-leather privateers, were already gunning for pole position. As the session wound down, I settled in and began to drop my lap times, though not nearly quickly enough to be seeded within the faster half of the field once we were divided into two groups for qualifying later in the day.

Characteristic of a standard CBR, the Erion racer was easy to ride in every respect. Running baseline suspension settings the team had come up with during pre-season tests provided superb stability on the banking and a very settled feel while braking hard into corners. I was also impressed with the new CBR’s light, agile handling through the infield portion of the roadcourse and the ease with which it made side-to-side transitions through the third-gear chicane. The power and feel of the front brakes was spot on, allowing them to be trailed deep into corners.

The engine’s spread of useful power spans about 7000 rpm, which allowed second-gear drives out certain infield corners from deep in its midrange revs. Feeling no sudden increase in the power delivery, I found that full-throttle exits while still leaned over were safe and predictable.

Where does extra power come from? Supersport lore tells us of enlarged piston clearance, of oil pumps made freespinning by being fed sand and of cylinder blocks offset to the front to relieve the power strokes of some of the burden of rod-angle-derived friction. If any such measures are in use today, no one ’s talking about them. There may be some use of friction-reducing coatings, but most extra power must come from ignition and fuel re-mapping, and from use of a continuous-blend valve job in place of the standard factory 3and 4-angle approximations. —KC

All told, my Honda worked so well that all I needed to concentrate on was hitting my marks and pushing my braking points a bit deeper as my confidence grew.

The new 600s from Honda and Kawasaki this year both feature mainly stronger midrange, and I believe this is an outgrowth of the primary direction of development in MotoGP. Endless revs and top-end power have achieved little there, but shorter valve timing, refined combustion and higher compression do boost midrange and acceleration. Don Sakakura at Yoshimura Suzuki said, “It’s been 16,000 revs, but now all the gains have been in acceleration.” This shouldn’t surprise anyone with Daytona experience. No one gears for top speed on the banking because that makes the gearing > too tall for the acceleration needed in the infield and off the chicane. At least one bike was geared to use only the first five ratios, giving its rider the extra advantage of first gear’s lower ratio. Acceleration is the engine quality that wins races, and that is controlled by the average power that the engine makes, across the rpm band actually used in the race. We are traditionally attracted to peak power because it ’s easy to measure and everyone advertises it, so it makes good cocktail party conversation. But it seldom wins races. -KC

A rear sprocket change was made following the first session as taller gearing was needed to avoid bumping into the rev-limiter when catching a draft around the bowl. When I mentioned the initial on-throttle response was a little sharper than I needed, Erion’s Rick Hobbs connected a laptop and tweaked the fuel mapping to soften the transition-a task that would have been quite involved on the carbureted Yamaha R6 I raced here in ’99 took less than a minute’s work.

Asked how much trackside computer work was necessaiy, Hobbs replied, “In Supersport, after the initial mapping, very little." When I examined the bike, there was a Dynojet Power Commander, allowing re-mapping of the stock fuel and ignition with performance as their single> goal. When Canet had asked Erion about Supersport rear-wheel power, he had said “About 120.“ On the CWrear-wheel dyno, a new 600 typically makes 105. KC

Since the bike was equipped with an on-board lap timer, I could see that catching a tow around the bowl equated to a lap time that was about a full second quicker. With that in mind, I headed out in the qualifying session on the lookout for a drafting partner but found myself circulating alone, turning laps in the 1minute 48-second range. I pitted late in the session so Smith could fit our second rear wheel shod with a “Q”-paddockspeak for a soft-compound qualifying tire. Dunlop, one of Erion’s sponsors, took good care of me, allocating five fronts and as many race rears along with the unexpected bonus of a one-lap wonder qualifier. The Q was said to be good for about 1-second-quicker lap times compared to a race tire.

As advertised, my time dropped into the 1:47 bracket with the softer tire. Unfortunately, I still hadn’t benefited from catching another rider’s draft. This put me 43rd fastest among the 62 riders who made the cut by clocking a lap within 110-percent of the blistering-fast 1:41.8 turned in by factory Kawasaki pole-sitter and reigning class champion Jamie Hacking. What’s truly astounding is the fact that the pole time for the 200 set by Honda’s Miguel Duhamel riding an extensively modified FX machine was only .8 of a second quicker.

Attempts to race big four-stroke machines in the 1970s required extensive re-engineering, producing the legendary 1025cc Superbikes of that era. In the 1980s, the first out-of-the-box produc tion-raceable four-strokes appeared-ma chines with better chassis and more reli able (often liquid-cooled) engines. These were bikes like Kawasaki s' pioneering 550s and 600s, and Honda Interceptorsthe first machines to prove that handling qualities could be marketable. Steady evo

lution of sophistication has brought us to this moment when there is little to choose between limited-mods and all-out classes-even on afast track like Daytona. Twenty-five years of racing savvy have been condensed into todays production machines. -KC

Looking over the qualifying times, I found a few familiar names-guys I raced with way back when. Hey, starting a row ahead of me was David Sadowski, a former factory rider and Daytona 200 winner. “Ski” beat me in a good battle at the Suzuki Cup Finals in 1992. Maybe Fll get another crack at him here? Just when I’m beginning to feel a bit of fire inside, I learn it’s David Sadowski Jr., Dave’s 20-yearold son. Now I’m really feeling my age.

I line up on Row 11 for the start, the first of the second wave. We get the green light 20 seconds after the 10-row-deep lead pack has left the line. Following a solid launch, I have clear track ahead into Turn 1. Problem is, I am still riding rather than racing, and I give in too easily when showed a wheel on the inside, then get passed by another pair of bikes on the outside as I ease into the first corner. In fact, I ride that entire first lap like a re sponsible citizen with a mortgage to pay and mouths to feed. While there isn't much monetary incentive in the $225 paid out for the 20th and final purse po sition, the sight of losing ground to bikes ahead of me is more than I can stand.

I feel the competitive spirit well up inside and find the focus and determina tion to give chase; nothing else matters. I now tuck in a bit tighter on the bank ing, run it in deeper before braking and get back in the throttle sooner when ex iting corners. While the sum of my ef fort results in shaving a second off my lap time, more importantly I've found rhythm and consistency. Closing on and overtaking riders feeds the soul. I am working hard and truly enjoying the work. With the R6-mounted Slovenian hot> on my tail, I begin the final lap. I hold it on as deep as I dare into Turn 1 before applying the brakes and proceed to maintain position through the infield and onto the back straight leading to the chicane. I’ve learned the hard way in the past that it’s better to be the hunter rather than the hunted when it comes to working the draft in the final run from the chicane to the finish.

Holding a wide line entering the chicane leaves an open invitation that the R6 rider accepts, allowing me to duck in behind him and take up chase through the chicane and onto the banking. It seems I am gaining ground too quickly, leading me to suspect the guy is sandbagging in an effort to get me back in front of him-a classic game of cat and mouse. Patience has come with age, though, and I hold my distance until we came off NASCAR 4 before beginning my run. Closing up on his rear tire, I pull out of his draft at the last possible moment, committing to an outside pass as we bend into the shallow banked tri-oval.

I must have held my breath from that point until crossing the finish several hundred yards down track, because it was during that suspended moment of uncertainty, not knowing whether I had the momentum to complete the pass, that I rediscovered the reason I love to race. □

For additional Rust Removal photography, visit www.cycleworld.com

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAn Immodest Proposal

June 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Blue Angel Syndrome

June 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCConvention, Unconvention

June 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2007 By Iector Cademartori -

Roundup

RoundupBmw's 450 Revolution

June 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMv Agusta's Race Special

June 2007 By Blake Conner